On Tuesday, President Joe Biden signed into law what will likely be the cornerstone of the Democrats’ pitch to the American public to keep them in majority power—the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022. Building on the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) of 2021, the IRA has won wide acclaim as the “single biggest climate investment” in United States history, with close to $370 billion dedicated to clean energy manufacturing, building efficiency, electric vehicles, and other climate provisions. (Another approximately $100 billion will go toward extending provisions of the Affordable Care Act, including language to boost Medicare’s ability to negotiate lower prescription drug costs, and to expand Medicare’s free vaccine coverage.) But this latest compromise between corporate-aligned liberals and social democracy-aligned progressives in the Democratic Party is not without flaws—nor should it be immune from criticism.

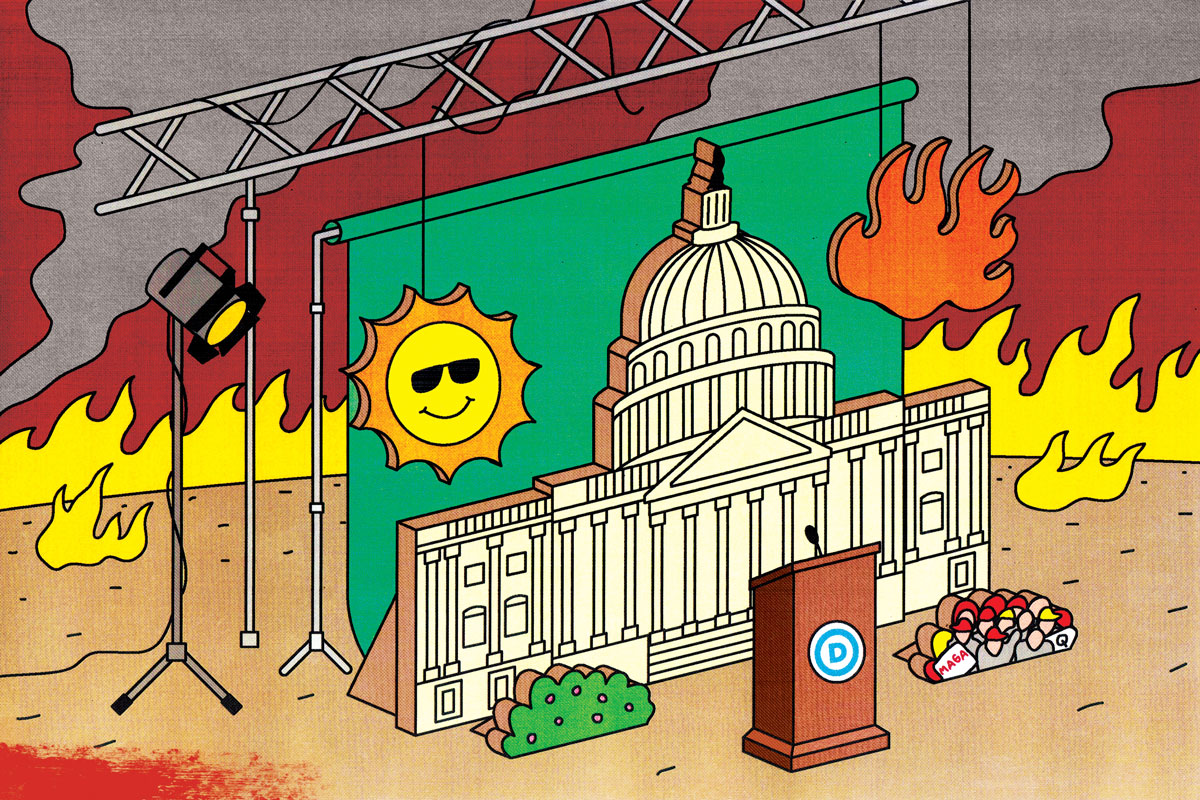

As the IRA moved through Congress on the strength of a surprise deal with longtime refusenik Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia, environmental and climate justice organizers and advocates increasingly expressed their concern with the bill’s overall framework. In particular, they targeted a massive giveaway of public lands to oil and gas companies, along with other concessions to dirty energy barons obscured by the broader political theater of Washington-branded pragmatism.

These organizers and advocates argue that, despite the continuous invocation of “environmental justice” by congressional Democrats and the White House, the IRA is, in its overall impact, more of the same—a major piece of legislation, yes, but one predicated on tradeoffs that sacrifice the health, safety and vitality of Black and brown communities locally for the mere prospect (not guarantee) of corporate “eco-innovation” and under-specified transitions to clean energy nationally.

The Inflation Reduction Act is a budget reconciliation bill that institutes changes to climate and energy policy as well as to health care and tax reform. When enacted, the IRA will infuse our sluggish economy with roughly $469 billion in total spending and tax breaks, and avoid the onset of a recession. (Even though some would argue we’re already in a recession.) The IRA is also designed to generate around $765 billion in revenue from cost savings, raising taxes creatively on tax-dodging corporations, and focusing on recouping taxes from wealthy households making more than $400,000 annually. Although the IRA’s lead provisions represent a considerably downsized version of the Biden White House’s far more sweeping Build Back Better (BBB) Act, the new law represents long-overdue climate investments. What’s more, it almost didn’t happen.

In early 2021, the White House and progressive Democrats in Congress unveiled competing spending plans to fulfill their 2020 campaign promises and relieve the many pressing needs that Americans were facing—e.g. rising medical and student loan debt, housing insecurity and homelessness, crumbling public infrastructure, worker burnout, more frequent climate disasters, long-lasting legacies of pollution, and vast health inequities. The Biden administration initially proposed a $4 trillion budget proposal, while progressives in both chambers introduced the Transform, Heal and Renew by Investing in a Vibrant Economy (THRIVE) Act, a $10 trillion proposal to reduce racial inequality through deep investments in renewable energy, green infrastructure, public transportation, public housing, and other climate justice initiatives.

To find a middle ground, Senate Budget Committee Chairman Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) floated the idea of using the Democratic majority to pass a $6 trillion budget package. However, these plans were swiftly dashed, not by Republicans, but by fellow Democrats on his right, including Sens. Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema (D-Az.). They both claimed the large spending would increase the national debt and worsen inflation, whittling the amount for the proposed budget package down to $3.5 trillion. With friends like these in the Democratic party, who needs enemies?

Continuing to shower treats on oil and gas interests, Senate Democratic leaders also agreed to reinstate canceled oil and gas lease sales, auction off more public lands and water for oil and gas drilling, and prioritize oil and gas leases before solar and wind lease offerings.

The $3.5 trillion proposal was composed of the $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which focused on built infrastructure and the $2.3 trillion Build Back Better Act concentrating chiefly on social welfare infrastructure. While the Senate Democrats managed to reach consensus around the IIJA, corporate-aligned liberals continued to push back on social spending provisions and new taxation. Progressive Democrats—including the high-profile members of “the Squad” in the House—warned that their leverage for much-needed social spending (for childcare, paid leave, universal pre-K, housing, immigration, etc.) would be lost if the two bills were decoupled. Nevertheless, House leadership agreed to split the IIJA and BBB and hold separate votes—first on the IIJA and then the BBB soon after. And, as forewarned, once the IIJA became law, Sen. Manchin came out in public opposition on Fox News to BBB, stalling negotiations just before Christmas.

Despite repeated attempts to resume negotiations on Build Back Better this year, Sen. Manchin remained staunchly opposed to it until something shifted this spring.

A coal baron himself, Manchin knew that his key constituency—the fossil fuel industry—was experiencing a string of defeats. Environmentalists were working the federal legal and regulatory apparatus to slow down and block new oil and gas drilling, pipelines, and export terminals, and citing immediate threats these projects posed to wildlife, the planet and the health of Americans living near fossil fuel infrastructure, suffering from the air and water pollution hazards that accompany it, and violating their civil and human rights. (This latter group is also disproportionately Black, Latino, and Native American.) Plus, the five-year federal offshore oil and gas leasing program was set to expire this June.

Manchin let it be known that he was finally open to making a deal just before Congress’s August recess. He met with Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) and other key Senate players to spell out the types of climate and energy policies he would be open to including in a drastically scaled down version of Build Back Better to be known, in the austerity-friendly argot of Washington, as the Inflation Reduction Act. (Contrary to the name, the IRA likely won’t do much to substantively or quickly lower inflation.) While inimical to electric vehicles, Manchin said he’d sign off on tax breaks for clean energy manufacturing and more controversial investments in hydrogen energy and carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS). This provided a window for liberal senators, such as Schumer and Ron Wyden (D-Or.), and environmental and sustainability groups to try a new “carrot-driven” approach and negotiate a narrower, sweeter deal that Manchin couldn’t refuse.

For all its diminished policy and spending ambition, the IRA does erect some new policy mechanisms to combat the present climate emergency. For nearly 30 years, Democrats have tried to advance carbon mitigation strategies based on market-based schemes of carbon pricing, such as cap-and-trade and carbon taxes or fees. The thinking here was both to appease Republicans in the holy yet ever-elusive quest for bipartisan accord and to push big carbon-emitting industries and companies toward greener business practices. The IRA is sidestepping this inert set of roundabout, market-driven regulations in favor of a wide array of corporate-friendly “green” tax incentives. In regard to outcomes, one key continuity between the two approaches remains—like the neoliberal market-based mechanisms for carbon mitigation, the IRA does very little to rein in or end the fossil fuel industry. To keep Manchin at the table, Schumer, with support from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Ca.), promised to hold a separate vote on expediting the permitting process for future fossil fuel infrastructure, which may revive stalled pipeline projects such as the Mountain Valley Pipeline in Manchin’s home state of West Virginia.

Continuing to shower treats on oil and gas interests, Senate Democratic leaders also agreed to reinstate canceled oil and gas lease sales, auction off more public lands and water for oil and gas drilling, and prioritize oil and gas leases before solar and wind lease offerings. They agreed to institute tax credits that will help scale up hydrogen and CCUS projects—still unproven technologies developed and favored by the oil and gas industry and their investors. Progressive environmental groups and environmental justice advocates strongly oppose these large-scale, capital-intensive projects, noting that they will only extend the life of fossil-fuel infrastructure and practices.

When the dust settled on negotiations, the Inflation Reduction Act totaled about $469 billion—a far cry from the proposed $2.3 trillion originally designated for BBB, and nowhere near the $10 trillion THRIVE Act supported by congressional progressives. Still, the IRA is estimated to drop greenhouse gas emissions nationally by 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, which would bring the Biden administration much closer to its announced 50 percent carbon-reduction goal. So the various factions of the Democratic Party came together to pass the IRA along party lines in the Senate, with a tie-breaking vote by Vice President Kamala Harris; the House endorsed it in short order prior to the official White House signing ceremony earlier this week.

Given the whirlwind pace of legislative brokering around the bill and the long excruciatingly stalemated negotiations around Build Back Better, it’s not surprising that many traditional Washington constituencies—from politicians to industry executives to mainstream environmental groups—breathed a deep sigh of relief and celebrated the IRA’s passage. Why, then, were some environmental and climate justice advocates and organizers so reluctant to join the chorus—and indeed declared themselves in open opposition to this monumental bill?

In environmental and climate justice spaces, there is a concept known as “sacrifice zones.” This concept denotes the ways that predominantly Black and brown neighborhoods—regardless of income—together with the natural and cultural sites they value, have historically been zoned for the most toxic, environmentally destructive businesses, such as fracking, waste dumping, and concentrated animal feeding operations. These harms are visited on these communities simply because they are “the other.” This holds true even if such sites are not, in strict market terms, the most geographically or financially convenient locations. Centuries of American policymaking and business practices have institutionalized sacrifice zones as the de facto backdrop of dirty industrial policy—creating a vast legacy of environmental racism and injustice.

Many of the concessions to fossil-fuel interests that the liberal wing of the Democratic Party has funneled into the IRA and labeled “environmental justice” do very little to directly address the pressing mandates of the environmental justice movement.

So when the purveyors of status quo, backdoor politics devise new public policies today that do not fix this unjust legacy nor implement strategies to prevent new harms, environmental and climate justice advocates and organizers will rightfully stand up to rebuff the pending adverse impacts on existing sacrificed communities and neighborhoods. Unlike mainstream environmental and sustainability groups, these groups do not view carbon emission reductions as their only goal. In line with the principles of environmental justice, public policies must also demonstrate precisely how they will directly save and improve the lives of Black and brown people already burdened by big polluting industries without any additional sacrifices on their part. To environmental and climate justice advocates, successful long-term climate action and a just, equitable transition out of the extractive age of fossil-fuel-driven society require addressing environmental racism head on. And they recognize that without directly disrupting the policies and business practices driving environmental racism, we will continue, as a nation, to recreate racial disparities, even as our economy becomes greener.

Undoubtedly, the IRA does include billions of dollars in tax credits and grants for clean electricity, energy storage, and building efficiency upgrades, which is a good thing. It also helps underwrite the expansion of domestic manufacturing of solar panels and cells, wind turbines, heat pumps, batteries, and critical minerals, which will create new American jobs although they are not targeted to overcome racial disparities in the clean energy industry. The new law provides a wide range of incentives to convert commercial and industrial vehicle fleets to electric vehicles (EVs) and encourage the domestic production and use of biofuels. These and many other key measures in the law are intended to lure American companies towards a clean energy transition and reduce their harmful impacts on disadvantaged communities. The IRA also expands tax rebates for individuals and families to improve energy efficiency in their homes, electrify their gas-powered home appliances, and purchase new or used electric vehicles for their personal use.

In acknowledgment of at least some demands of prominent environmental justice leaders, congressional Democrats also included in the IRA some provisions for grants to local and state governments, companies, and nonprofits to reduce legacy pollution and to transition to zero-emissions school buses, transit buses, postal trucks and garbage trucks. The bill also includes outlays for improved air pollution monitoring and for stimulus plans to create new jobs in urban forestry and water supply projects in disadvantaged, rural and tribal communities. There are also targeted credits in the law for home energy tax rebate programs that promote energy efficiency as well as solar panel installation in low-income and disadvantaged communities.

Still, the fact remains that many of the concessions to fossil-fuel interests that the liberal wing of the Democratic Party has funneled into the IRA and labeled “environmental justice” do very little to directly address the pressing mandates of the environmental justice movement and its sister climate justice movement, or to undo the generations-long damage inflicted on the nation’s sacrifice zones and fence-line communities. The law has no provisions to rein in and stop the ongoing pollution and related health impacts caused by the fossil fuel industry, industrial agriculture, or even the U.S. military. And the law’s provisions do very little to proffer tangible and material support for Black and brown families threatened right now by the rise in sea levels, wildfires, hurricanes, flooding and other potential climate disasters—and who do not have the means to rebuild or flee. The language of the IRA also gives comparatively free rein to states controlled by big oil and other climate-denying interests to redirect much of the IRA funding to other uses that will worsen our racial divide in environmental, agricultural, housing, and economic policy rather than helping to close it.

For a large contingent of environmental and climate justice advocates and organizers, the IRA is the latest example of Democrats selling out people of color, particularly those who are cash-strapped and indebted, in the interest of political expediency and “getting a win” before the midterms. A number of environmental and climate justice organizations and coalitions, including The Black Hive, the Climate Justice Alliance, the Grassroots Global Justice Alliance, the Indigenous Environmental Network, the Native Movement and others, have all released statements denouncing the IRA’s tragically limited approach to fundamental questions of environmental racism and climate justice. Anthony Rogers-Wright, a Black board member of the mainstream climate action group Evergreen Action, which was a key crafter and negotiator for the IRA, publicly resigned over its support for the racially blinkered set of policies endorsed under the law.

It is unclear how the Biden administration and Democrats will explain their actions to Americans of color during the coming midterms (or in election seasons thereafter) or when the next big environmental or climate calamity hits, whichever happens first. But for the forces seeking coordinated environmental and climate action and racial justice, a more profound question presents itself: Considering all that we’ve had to endure, when will Black, Indigenous and other people of color stop being the sacrificial lamb on the United States’ discriminatory and cruel climate and energy altar?

J. Ama Mantey, Ph.D. is a biomedical scientist turned policy professional and freelance writer. A proud two-time HBCU alumna, she writes about the social, cultural, and political implications and intersections of race, science, technology, public health and the environment.