In his recently published book, Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (and Everything Else), Georgetown University Philosophy Professor Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò lays bare some key tensions within the intersecting campaigns for racial justice, gender equity, and climate-change mitigation. He examines how the dynamics of elite capture—the process under which corrupt postcolonialist governments have hijacked resources earmarked for populations in need—have operated to foreshorten the moral imagination of liberal reform, and miniaturize it into an elite-managed politics of symbolic representation. In conversation with Forum editor-in-chief Chris Lehmann, Táíwò discusses the broad implications of his critique, and revisits the original vision of identity politics as a touchstone for global solidarity. This discussion has been edited for clarity and length.

Chris Lehmann:

Can you talk about how the critique of identity politics in Elite Capture differs from what I think of as a vulgar critique of identity politics, which basically translates into, “Let’s not talk about race”?

Olúfẹ́mi Táíwò:

Well, at the end of the day, I’m on team identity politics. And the criticism I’m making is not about whether we’re doing identity politics, but about how we’re doing identity politics.

Lehmann:

Right. But what would you say to the Mark Lilla faction in liberal politics or the signatories of the Harper’s Letter? I guess this is another way of saying I think the vulgar critique of identity politics among liberals has morphed into this free-floating panic about wokeness or cancel culture—the idea that a battalion of the language police is turning off an ill-defined (but usually white) centrist faction in our politics.

Táíwò:

Yeah. I think one of the things that I’ve been trying to understand without caricaturing is what the criticism is supposed to be from the progressive center.

So if you’re on the center left, I think people are widely of the opinion that, in some vague sense, they oppose bigotry. But they just don’t seem to think that they need to organize around that kind of opposition. So if we just focus on jobs and the economy and dinner table bread-and-butter issues, the rest will sort itself out.

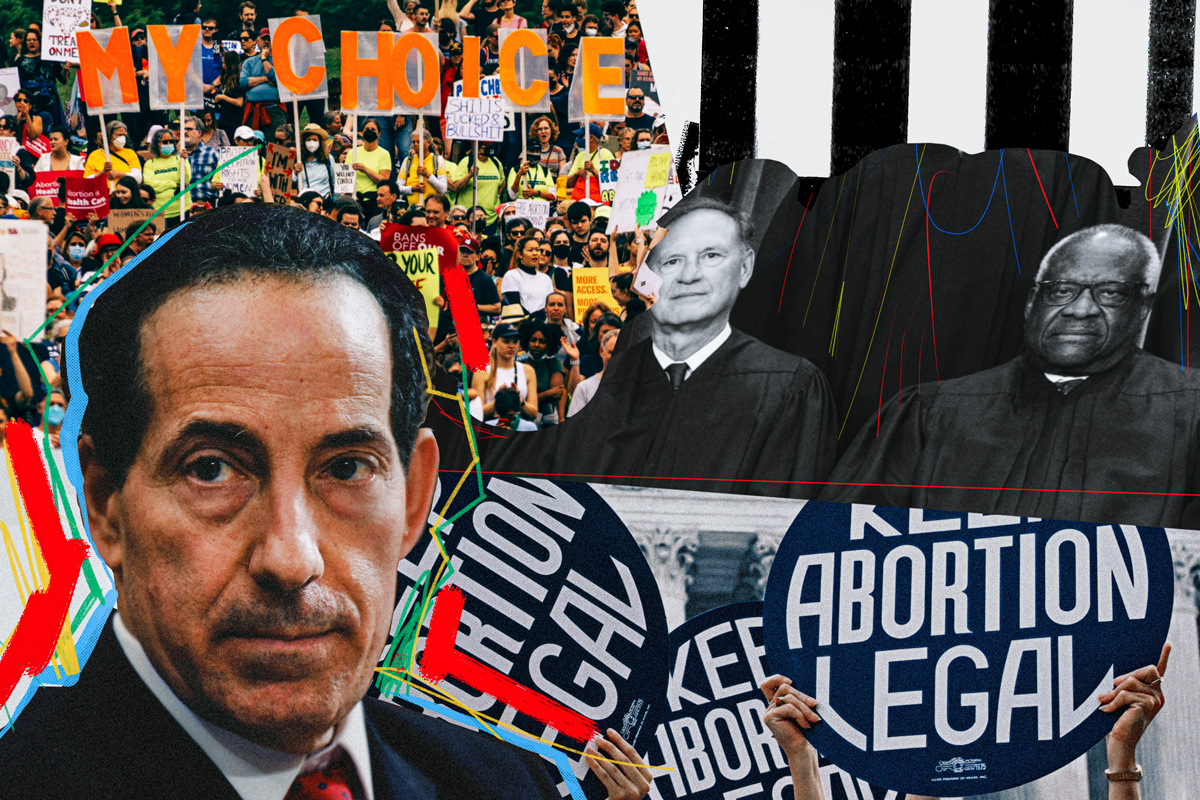

I don’t think that’s ever been too plausible of a view, just looking historically at how the right wing has, in fact, organized itself and how U.S. political institutions have, in fact, organized themselves. But in the era of what we’re having now, widespread great replacement theory in the highest reaches of government, mass shootings in Buffalo, the court looking at overturning Roe v. Wade, it just seems more and more demonstrably false from the point of view of widely accessible mass media.

And we’re not even talking about needing to do a deep dive into local politics to see how these institutions are actually functioning. If you look at front-page headlines, you can see that there’s actually a pretty broad cultural offensive by the right wing. And they’re not just coming for profit margins. They are coming for social liberties that we might have thought were safe. And [we can’t pretend] that we were just going to maybe generationally age out of challenges to marriage equality or abortion access, or the worst versions of racial fascism.

Lehmann:

Yeah. AAPF has been very much on the receiving end of that cultural offensive on the right over the past two years. And in fact, CRT shares the same roots in the Combahee River Collective critique. I was so grateful in the book that you began essentially with that document and point out that the whole project of identity politics, as it was originally articulated, is to build coalitions. It is not to assert an inviolate, essentialist racial identity that no one else can critique. It is actually to collaborate and, one hopes, to win politically.

Táíwò:

So one of the caricatures of identity politics that traffics [among critics] is this idea of the oppression Olympics or inverted hierarchy of oppression. And it’s just interesting to me that that caricature proliferates, and I get why it does.

But one of the things that I often do is I reread the Combahee River statement, the original statement. Identity politics, if I recall correctly, only appears once in the document.

Now you have people not trying to launder their social control through the veneer of democracy, but increasingly willing to out-and-out question whether the sacred cow of democracy is even a good idea.

And the one time they say it, in that very same paragraph, they end the paragraph by saying, “we reject pedestals, queenhood and walking 10 paces behind. To be recognized as human, levelly human, is enough.” It’s not about being ahead or behind everybody else. It’s about what would actually be required for us to have real meaningful substantive equality, not replacing inequality with a different hierarchy.

Lehmann:

Yeah. It’s a call for solidarity, which is often the great missing term in American political philosophy. And since you write so well about liberation movements outside the United States and approach this from a different global perspective, what are the forces you see in the American political tradition that tend to promote the decomposition of an idea of shoulder-to-shoulder solidarity into a very individualist and elite-captured corporate discourse? Is that just the incorrigible libertarian strain of American politics? Is it capitalism? Is it all of the above?

Táíwò:

It’s all the above, but I think these things come together in really contingent ways based on historical developments rather than iron laws of how any of those things function.

So you had a proliferation of attention to issues of identity in a very radical global moment—the wave of national independence movements following the second world war, the Cold War, and the ideological struggle that came with that, between capitalism and communism and socialism. And in the aftermath, in the ashes of that conflict, you have on the one hand, the ascendance of the countries and corporations that had supported capitalism.

You have, in the United States, an emerging student-debt disciplinary apparatus which is very expensive. You have to make money to pay back your tuition, and which are the lucrative places to make money? Well, it’s not the places that are proliferating the global Third World solidarity version of thinking about identity politics.

And alongside all of these [developments] comes the decimation of the labor movement, so the kinds of organizations that would have naturally incubated different ways of thinking about identity politics get beaten back—whether by Reagan breaking up PATCO [the air traffic controllers’ union] or by right-to-work legislation. And in this same neoliberal moment, the kinds of institutions that would reward and incubate more individually focused and capitalism-friendly versions of thinking about identity politics are more and more culturally, politically and economically ascendant.

And the rest is just the straightforward sociological results of those phenomena.

Lehmann:

And there is also a big culture component there, I think, as well. At the Baffler, which I used to edit, we were, in the nineties, critiquing what was then a rampant rhetoric of corporate liberationism and consumer sovereignty. I think it has now morphed into something much worse under the pressures of neoliberalism and Trumpism and the opening of this path of degraded populism on the right. What do you think might be the next iterations of this unholy alliance of corporate capitalism and identity politics as you see it?

Táíwò:

I mean, I see a whole ecology of right wing movements gaining steam in the U.S. and globally.

The biggest one, by the numbers, is probably the BJP in India. But outside of India, in Germany, in Brazil, in the United States, you have a resurgence of ideologies that had never really gone anywhere, but had not had the kind of historical conditions for as much recruiting success. And they didn’t have as much collusion from the powers that be in the initial decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, where the neoliberal technocratic consensus was so dominant and hegemonic. Now you have people not trying to launder their social control through the veneer of democracy, but increasingly willing to out-and-out question whether the sacred cow of democracy is even a good idea in the abstract—much less whether they actually would like to live up to it in terms of how they run political institutions and elections.

So increasingly, we’re going to see a clown car of economic opportunists. I can’t tell if Alex Jones and Tucker Carlson really believe the things that they’re saying, sort of believe the things that they’re saying, but really believe in making money off of male vitality supplements and testicular tanners, or if they’re just totally clear-mindedly exploiting the sort of people that build their audiences. But there’s going to be people who are somewhere on that spectrum. There’s going to be more and more recruiting for the organized hard right. I think the coming battles over Roe v. Wade are going to be a clear pathway in for a lot of people on issues related to the trans panic as well, the persecution of trans kids and their parents throughout full swaths of the country. The Catholic right is seeing a resurgence around these issues.

Lehmann:

You might say especially on the Supreme Court.

Táíwò:

Absolutely. Right. You don’t need numbers if you have the strategic positions. The numbers you might need are five out of nine rather than tens of millions out of hundreds of millions.

Lehmann:

It seems clear, reviewing Carlson’s career from MSNBC to “Dancing with the Stars” up through today, he was desperate for mass attention from the word go. And finally, everything clicked in this way. And I think that takes us back to the capitalism question—all of these directions you outlined are now incentivized by the market. When you were talking about the rejection of democracy, you know that Peter Thiel famously wrote that capitalism and democracy are incompatible and that means capitalism has to win. In the face of all these incentives on the right, what would you say are the three central priorities that we need to adopt tomorrow to really galvanize resistance to these trends?

Táíwò:

One is organizational capacity, right? So sometimes when people talk about capitalism, particularly people coming from particular strains of Marxist and anarchist perspectives, there’s a way of, I think, taking the laws of motion of capital a little too seriously from a political perspective. So there’s an effort to translate everything that people are trying to do into something explicable by the profit motive.

So, Tucker Carlson, as an example, [this critique says] maybe it’s all just a complicated way to sell testicular tanners. And I don’t think that’s right. A better way to think about it is people are complicated and they have lots of desires and lots of goals, and there are lots of potential combinations of the desires and goals that different people have. And if you weight those by money, if you ask which people’s desires are likely to actually turn into tangible, sustainable organizing, which people have the resources to actually act in a sustainable long-term way in service of their desires, then you’re going to find the people who have the most money and resources disproportionately.

So that’s the connection between what’s happening politically and money and profit. It’s not about money and profit unilaterally deciding what politics is going to be. But it does decide who has this particular really important kind of advantage in doing whatever it is that they’re motivated to do politically.

And so if you’re siding with the people who have less money, right, the proletarians, the masses, the 99 percent, then you’re starting with people who have a particularly important structural disadvantage, and that’s a gap that you have to figure out how to make up.

And that’s the appeal of unions and worker-supporting legislation and whatever it is that we can do to constrain the power of the economic elites and redouble the power of the rest of people. We’re just trying to even up the playing field. And until we even up the playing field, we’re going to be dependent on appeals to the pretend decency of people who, in fact, don’t have decency.

- Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (and Everything Else), by Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò; Haymarket Books, 2022

Lehmann:

Yeah. And I think that’s where your critique of what I have called in shorthand, the HR version of identity politics, is especially powerful. This notion that in very socially attenuated, symbolic settings, you center the voice and the experience of someone who represents a historically marginalized community, you have to ask who’s benefiting here. In many cases, it’s a feel-good exercise to make corporations both less liable in prospective anti-discrimination actions and to feel like good global citizens when their actual conduct may strongly indicate otherwise. If this is how many people encounter the idea of identity politics, how recoverable is it?

Táíwò:

Yeah. I mean, certainly not their version. And it has more to do with how corporations work than even the intellectual shortcomings of corporate diversity culture, of which there are many, but at the end of the day, corporations are a structure that is very explicitly authoritarian. Your boss says you’re fired, you’re fired. There’s no vote. And so the question is just in that context, is there a version of identity politics that is likely to be incompatible with the interests of that institution? Unlikely.

But in the workers unions organized within those corporations, is there a version of identity politics that is likely to be more helpful from a political perspective? And I think the answer to that is definitely yes.

Lehmann:

Yeah. And you’re seeing that now with Christian Smalls and the Amazon organizing movement. That’s a great example of an expansive, racially conscious model of worker equity that is working against one of the largest corporations in the world.

Táíwò:

Absolutely.

Lehmann:

So Georgetown, where you teach, has been at the center of a number of contretemps, to put it delicately, around identity politics. What have been your experiences of how identity politics has been playing out in your own workplace?

Táíwò:

I mean, it’s been a mixed bag. I think there are people who have gravitated towards identity politics, but in a way that’s very focused on the very real versions of oppression, racism, patriarchy, what have you, that show up in academic spaces. And then you have people who are alive to those issues, but also use identity politics as a lens towards the broader social ramifications of all those same ills.

And clearly, I’m siding with group number two there, but I think there are difficult questions to ask about balance. Workers of any kind, academic or otherwise, are right to take an interest in the working conditions of where they work.

That’s part and parcel of how workers should relate to a broader workers movement. And there’s always the question of how what’s going on on your shop floor connects with what’s going on elsewhere. But I don’t think it’s ever the right thing to say, to just tell people to be disinterested in the material conditions of their own lives.

But at the same time, there’s a needed perspective on how it is that we can all fit together and to what extent there should be a focus outside of a particular work setting on those issues.

Lehmann:

As you talk, I know you’re a philosopher and I’m just wondering, I don’t know if you consider yourself a Rortyan pragmatist, but your political program seems very closely aligned to the argument Richard Rorty put forward in Achieving Our Country and elsewhere.

Táíwò:

Yeah, I would say so. Definitely, there are a lot of affinities with pragmatism, in general, of the Rortyan or Deweyan varieties.

Lehmann:

That’s also a tradition focused on outcomes, that is less interested in the Kantian interrogation of deep motivations and all that. So in that spirit, I’ve been wondering a lot about ideology.

There are times when I find myself almost nursing a guilty nostalgia for the discipline of the Cold War in America. Famously, this is Derrick Bell’s argument, that there was an interest convergence with the Cold War in the Civil Rights Movement. And without it, you probably wouldn’t have had the Voting Rights Act and the Civil Rights Act. You also had McCarthyism and the Vietnam War, which is obviously a big problem. But there are some times when I look out on the political scene today and we don’t have a robust left in this country—we don’t even really have an organized left. And there is no countervailing force. The right can just keep blowing past all the norms and they don’t care if you call them racist. They don’t care if you call them anti-democratic. They’ll just say, “Yeah, what else you got?” So in the absence of that Cold War discipline, what ideologically needs to change in this country?

Táíwò:

I’m not sure how much can happen ideologically as opposed to just building that organizational capacity on the left again and using that to exert pressures of the non-ideological sort, the threat of strikes, etcetera. But I do think one thing that might help ideologically is this practical orientation that we were talking about just a second ago, because I don’t think it’s true that the culture wars are somehow a distraction from real politics.

Until we even up the playing field, we’re going to be dependent on appeals to the pretend decency of people who, in fact, don’t have decency.

But the kernel of truth in the criticism of people who say that the culture wars are a distraction is that the culture wars are certainly dishonest about their connection to real politics. The culture wars are the version of real politics that we get when the ruling class doesn’t want the political questions of the day to be about the things that are actually hard substantive issues.

What’s the ruling class answer to Covid? To apparently ignore it and hope it goes away, essentially.

Lehmann:

Right, or to throw us all into what my friend Max Alvarez calls the Hobbesian hellscape, where you’re hoarding your Covid tests and you’re just in this perpetual defensive crouch because there is no support system anywhere. There’s no public health protocol.

Táíwò:

Yeah. Not even provision of information in a timely digestible way. What’s the ruling class answer to climate crisis?

Lehmann:

Again, to hope it goes away, or to deny it exists.

Táíwò:

Yeah. Bury their heads in the sand. So as soon as the powers that be feel that they personally are safe, as soon as they are vaccinated, as soon as they have their little compound and Bill Gates has his farmland and so on—as soon as their portfolios and bodies are protected, then it’s all jokes from there, right? It’s all herbal supplements and testicular tanning and school board disruptions. And they’re more than happy to allow robust political engagement on culture war issues that they only instrumentally care about in the absence of anything that even looks like a coherent plan on climate or whatever else might be happening. And so if nothing else, I think the pragmatic focus will help shift the parameters of political discussion in a way that might be ideologically helpful. If instead of saying why you should be afraid of trans kids, if the right wing had to explain why you shouldn’t have healthcare, they might be on less secure political footing.

Lehmann:

Right, or explain why they are the party of attempted coups and sedition. I still don’t really understand why Democrats don’t take up that theme.

Táíwò:

Exactly.

Lehmann:

I do think I audibly cheered when I came across the simple sentence in your book, “We can just do things.” I do think we do tend to lose sight of that because so much of our public life essentially has been subject to the steady enclosure of the commons in all sorts of ways. Just getting a doctor’s bill paid in this society is an epic undertaking and it leaves you broke. And the urgent task is to organize a real social democratic agenda ahead of the advance of authoritarian rule in the courts, in gerrymandered legislatures and the like.

Táíwò:

Yeah. But that is much likelier to happen when we have real centers of independent power outside of those institutions, rather than organizing to be complaining about the people who staff those institutions.

Chris Lehmann is editor-in-chief for the African American Policy Forum, and editor at large for The Baffler and The New Republic. He is also the author of The Money Cult: Capitalism, Christianity, and the Unmaking of the American Dream (Melville House, 2016).