In early 1865, the Confederacy began to realize its situation was hopeless. Union forces had seized supply lines and crucial ports, Sherman’s army was scorching its path across the South. Still, the retreating Confederate soldiers regrouped with hopes for one final stand. It would be in Hempstead, Texas, east of the Brazos River, where slavery had built a thriving region of cotton plantations. The land glimmered so lush and green that no less than a maid-of-honor to Queen Victoria described it as “the brightest and most luxuriant verdure I have seen in America.” Hempstead’s population swelled that March of 1865 as a division of 8,000 men arrived from Louisiana and awaited the arrival of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Davis never made it to Hempstead, and likely never intended to fight there; when he was captured in Georgia, hidden in his wife’s dress and dark shawl, weeks after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, many accounts suggest he intended to flee overseas with dreams of forming a government in exile. The soldiers, who first dismissed Lee’s surrender as nineteenth-century fake news, then dispersed by early June, as the Trans-Mississippi division joined the South’s surrender. Hempstead became the county seat of Waller County, where a historical plaque at the courthouse, erected during the 1960s, imbues that befuddled surrender with poignance, honor and brotherhood, memorializing “comrades-in-arms of the recent conflict left to walk their weary way home in one of the last sad scenes of the southern Confederacy.”

This was hardly the last sad scene in Waller County. The Reconstruction dream flickered, only to be crushed by the Ku Klux Klan. More lynchings took place in Waller County between 1877 and 1950 than in any other county in Texas. What violence and racial terror could not attain, the Texas whites-only Democratic primary achieved, shutting Black voters out of the only election that actually mattered in what was still then the Democratic “solid South.” Little has changed in this town that continued to romanticize the lost cause at the height of the civil rights movement, and pay homage to the “sad scene” of Confederate retreat in granite installed at the county’s center of justice. ”Racism from the cradle to the grave,” says DeWayne Charleston, the county’s first Black justice of the peace. The county jail in Hempstead is where Sandra Bland died in 2015, after a routine traffic stop for failing to signal a lane change led to her arrest, and according to police, her suicide (an account that’s adamantly disputed by her family).

Bland was about to begin a new job at Prairie View A&M University, established in 1876 when this was a Black majority county—one of the first Texas colleges to admit Black students and the first funded by the state. This predominantly Black university, which reclaimed the old Alta Vista plantation for a higher purpose, has provided a pathway for more than 70,000 students to earn a college degree. Yet Waller County being Waller County, the white political and legal establishment has worked tirelessly to build creative barriers to the ballot box that make it more difficult for the 8,100 students to vote than it is for the county’s white residents. These days, voter suppression masquerades as a race-neutral policy. The new regime of racialized voter suppression is subtle, with a veneer of reasonableness, erected and defended by politicians who insist they’re not actually doing what it’s clear they’re doing. They contend that Waller County has changed, even as they oversee enforcing suppression tactics that have guaranteed a white monopoly on power in a majority-minority county.

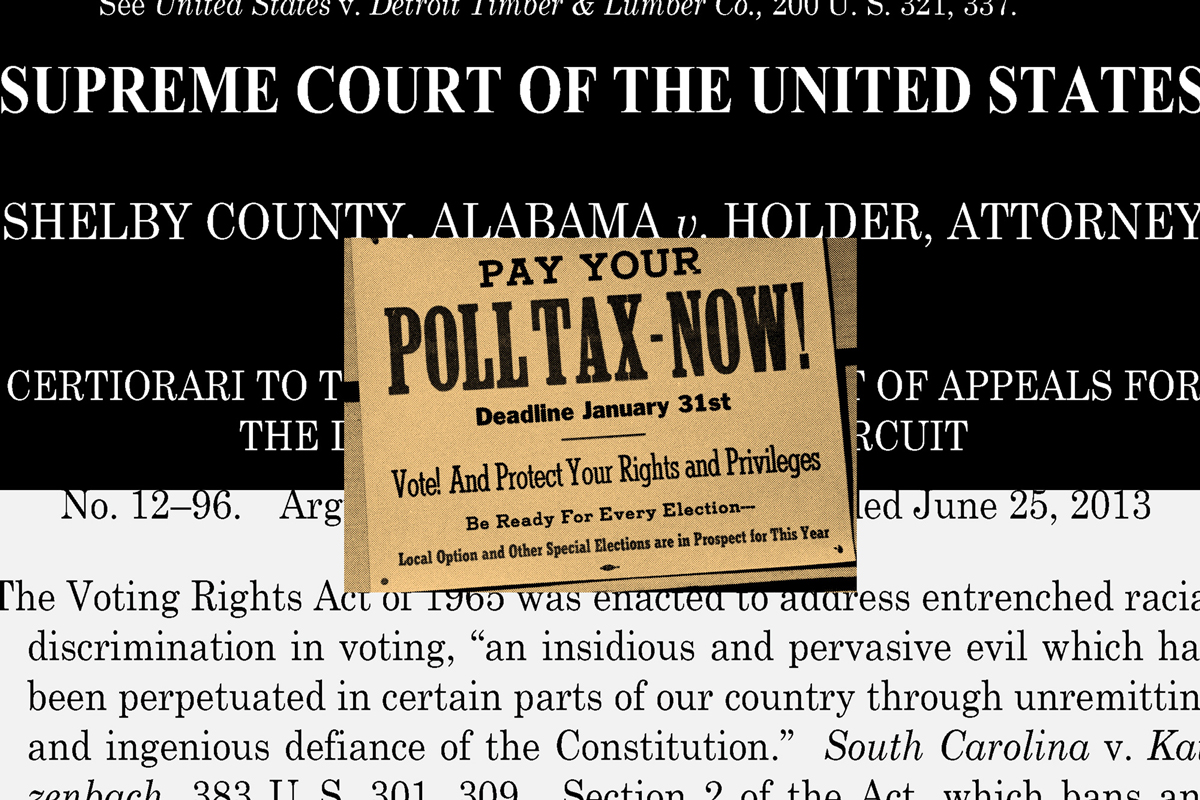

Name a trick and Waller County has tried it: Racial gerrymanders during the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s that cracked apart the Prairie View campus and diluted student voting strength for county elections by scattering them across multiple districts. Rejecting voter registration applications from Prairie View students under illegal, made-up criteria that officials—whoops—failed to pre-clear with the federal government. The Voting Rights Act had mandated this step because officials in counties like this behave precisely like this; in 2013, the Roberts Court blithely dismantled this protection in Shelby County v. Holder, declaring that a new era of race-neutral shangri-la had been delivered to the South—much as the officials of Waller County do today.

Waller County is a place in a county where you have to drive miles to vote, but also where failing to signal a lane change might lead to a mysterious death in a jail cell.

But the county’s coup-de-grace against ballot access arrived in time for early voting in 2018, a sequel to 2016 suppression efforts that originally looked to open just two early voting centers in Waller County—one about seven miles away from campus and the other nearly 20. In other words, Waller County is a place where you have to drive miles to vote, but also where failing to signal a lane change might lead to a mysterious death in a jail cell. In 2018, the county expanded early voting, well . . . anywhere white people lived. The Hempstead courthouse, with its granite ode to the Lost Cause, offered early voting all 12 days, morning through evening. Other white bastions received up to 11 days of early voting. The county reluctantly allowed just three days of early voting at the Prairie View student center, none of it during evening hours.

Students brought litigation in federal court, only to have a Trump appointee finger-wag them for being so hyper-sensitive to the sins of the past as to believe that leaders today would possibly make any decisions with racial animus in their hearts. At best, Judge Charles Eskridge sniffed, the students established that “a mere inconvenience,” and even then insisted “it’s rather doubtful” that the early voting hours “provided by Waller County to PVAMU students” can actually “be understood as creating any incremental inconvenience at all.”

The judge didn’t go so far as to demand that the Prairie View students write Waller County thank you notes for generously allowing them to cast ballots at all. But his legal reasoning certainly suggested that if they actually wanted to vote, they shouldn’t have any problem jumping across a few extra barriers to cast a ballot. It’s a curious principle—separate and unequal. One person, one vote—except Waller County’s white voters cast their ballots with ease. Black students are after-thoughts, scolded by a federal judge for expecting equal treatment—who then insists newfangled barriers really don’t make any difference at all.

Things have changed dramatically in the South, Chief Justice John Roberts argued in his Shelby County decision nearly a decade ago. Roberts, a former Justice Department election lawyer in the Reagan administration had at last succeeded in his life-long project to undo the Voting Rights Act with perhaps the most tragic and egregious misreading of our nation’s past and structures of racial power in the Court’s modern history. Roberts spent much of oral arguments in Shelby taunting Solicitor General Donald Verrilli with phony and misleading statistics purportedly showing that there’s a larger gap between Black and white voter turnout in Massachusetts than there is in Mississippi, and declaring that the Voting Rights Act had served its purpose by raising Black registration rates across the South. The gist of Roberts’ majority opinion in Shelby County was: How much longer must this law be on the books before it rides into the sunset and a well-earned retirement, allowing Americans to applaud politely and declare victory over ancient sins too unteachable for Florida social studies classes?

But Waller County shows how things didn’t actually change in the South. Voter suppression simply transformed into something more insidious. Voter registration numbers, after all, are hardly the point if the act of casting a ballot can be so exhausting that it hardly becomes worth the effort—especially if that vote has been drained of its power through relentless cracking and packing schemes. While Roberts and others cite those statistics as proof that VRA protections are no longer needed, voter suppression has shape-shifted into something newer and easier to disguise, dozens of additional burdens and inconveniences, one piled upon another, most of them invisible to white voters who never stand in these longer lines or who have cast their ballot in the same middle-school gymnasium since the 1980s.

Elsewhere, voters are effectively told: Sure, go ahead and register to vote (except where that too requires running some hellish Rube Goldberg bureaucratic contraption). Now there will be a different set of different rules affecting voters of color. There will be much longer lines. No water while you stand in them. Fewer precincts. Your precincts will move repeatedly, and then out-of-precinct ballots will be tossed aside. Early voting will be limited to what the jurisdiction deems to be the most convenient hours and times. Voter ID restrictions will be “surgically” designed to require the specific forms of identification legislative studies have determined Black and Latino voters and Native Americans and college students are less likely to have. Voter rolls will be purged in ways that disproportionately affect minority communities. College students will face targeted hurdles designed to discourage participation not only in Texas, but also in Iowa, Michigan, Florida and New Hampshire. Rural and Native American voters who live hours from a post office or polling place will be accused of “ballot harvesting” if a friend or neighbor drives their ballot to the nearest mailbox–even if they live where there are only a handful of post offices in a county the size of New Jersey.

A new study by Kevin Morris of the Brennan Center for Justice demonstrates just how targeted and racially motivated these new restrictions have become. Morris’s research shows that every state controlled by Republicans has not moved to enact new voting laws. And states that have large white-majority populations are decidedly unlikely to do so. Instead, he writes, “racially diverse states controlled by Republicans are far more likely to introduce and pass restrictive provisions.” Moreover, Morris concludes, it’s “representatives from the whitest districts in those racially diverse states”—as well as districts with the highest scores on a racial resentment test, or the whitest districts closest to Black districts in a diverse state—who are most likely to sponsor regressive vote-suppression measures. This is the point of the entire conservative voter suppression project: Preventing just enough voters in the most competitive and quickly changing states from being heard, and perpetuating white minority rule for as long as possible despite demographic change.

Conservative judges continue to uphold these efforts because they believe that each one might only affect a small handful of voters–or that the restrictions imposed on voting are ultimately too minor and significant to matter. “The mere fact that there is some disparity in impact does not necessarily mean that a system is not equally open,” Associate Justice Samuel Alito caterwauled in his majority opinion in 2020’s Brnovich v. DNC, allowing Arizona voting restrictions intentionally and effectively drawn to disproportionately affect Black and Latino voters to stand because “voting necessarily requires some effort and compliance with some rules” and “small disparities should not be artificially magnified.” (Lower courts said this wasn’t a small disparity at all, it was “large and disproportionate,” especially in a closely contested state.) Or federal judges will determine that reconfigured voting rules are a mere inconvenience and folks—well, some folks—should stop their ungrateful bellyaching and be grateful that they’re allowed to run a gantlet to cast a ballot in such a fine nation. Some in the media shrug as well, and dismiss as hyperbole any suggestion that Jim Crow 2.0 is on the march.

The entire project is to put these restrictions in place in rapidly changing swing states, and the accumulated weight of it all could be more than enough to tip a state like Georgia or Arizona at the presidential level in 2024.

But the academic research confirms the story that has been clear to anyone who’s paying attention and who’s even generally aware of the nation’s history. The entire project is to put these restrictions in place in rapidly changing swing states, and the accumulated weight of it all could be more than enough to tip a state like Georgia or Arizona at the presidential level in 2024. Alito might be willing to assume the good faith of legislators in fighting the scourge of voter fraud every time they propose another new law. But the rest of us can’t help but wonder why North Dakota—a state where voters who showed up to cast a ballot on election day hadn’t even needed to register in advance!—suddenly demanded a voter ID with a street address right after Native American voters (who lack street addresses on tribal land) proved decisive in electing a Democrat to the U.S. Senate in 2012. Or why the New Hampshire GOP enacted new residency requirements and suddenly tied college students’ ability to vote to an expensive and time-consuming car registration process after young voters tipped a U.S. Senate seat to a Democrat by 1,017 votes. Or why Crystal Mason in Tarrant County, Texas, got a five-year sentence for casting a provisional ballot with the approval of election officials, one ultimately not counted because she was on probation for a felony. This glaringly racialized and gerrymandered system has openly proliferated throughout the country even as the white voters in Pennsylvania, Florida, Wisconsin and Arizona who committed intentional voter fraud for Trump get slaps on the wrist.

Contrary to the pie-eyed reveries of Justices Roberts and Alito, the racial rigging of the vote is anything but a sign of beneficent social progress and legislative good faith. In a closely divided nation, where the most competitive and rapidly diversifying states can be decided by a handful of votes, each and every additional barrier matters.

President Biden won the popular vote in 2020 by approximately 7 million votes. He carried the Electoral College 306-232. Both of those margins appear decisive. But Biden’s victories in Arizona (just under 10,500 votes), Georgia (under 11,800 votes) and Wisconsin (fewer than 20,800 votes) provided 37 electors. If those 44,000 votes or so disappear—that’s 0.027 percent of the 159,000,000-plus ballots cast—well, do the math. Take those electors from Biden and award them to Trump and the result is a 269 tie, which pushes the election to the U.S. House. Each congressional delegation would then vote amongst themselves, and cast the state’s single vote. Even if Liz Cheney and Fred Upton push Wyoming and Michigan into the blue column, it’s hard to see how the GOP carries fewer than 25 delegations. The constitutional chaos would have been even more intense. Given the makeup of the House in 2020 and the U.S. Supreme Court, Donald Trump could have easily held onto the presidency, despite the margin of his popular defeat.

Next time will be different. If the Supreme Court holds that state legislatures have unfettered control over election laws and procedures next term in Moore v. Harper, the popular will in closely contested states could be upended by gerrymandered legislatures. There will also be new laws in Georgia, Arizona, Texas and Florida. They skim, repeatedly, just a little off the top. It needn’t add up to much.

But for voters on the ground, it adds up to a whole lot. In Georgia alone, voters wait an average of six minutes after 7 p.m. to cast a ballot in precincts where 90 percent of voters are white. When 90 percent of voters are Black, it’s an entirely different story: then, the wait leaps to 51 minutes, according to research by Stanford University and Georgia Public Broadcasting. Georgia closed 8 percent of its voting precincts between 2012 and 2018, and relocated 40 percent of them. The Atlanta Journal Constitution found that the combination of fewer precincts and much longer drives to those polling places could have deterred as many as 85,000 voters—disproportionately Black voters—from casting a ballot.

Then in 2021, citing nonexistent concerns about voter fraud and the need to safeguard the integrity of elections from public concern about voter fraud—unfounded concerns entirely ginned up by lawmakers—Georgia’s conservative state legislators closed this rigged circle with 92 additional pages of new restrictions and voting regulations. Virtually all these convoluted new barriers to ballot access make the process needlessly complicated and additionally burdensome. Not for everyone, certainly, but for some—notably those voters in the state’s four most heavily populated Black counties, now restricted to just 23 drop boxes, a sharp decline from the 94 made available during 2020. Those drop boxes will now only be available when government offices are open, making them far less convenient for anyone who works during the day. Georgia’s lawmakers have also added multiple new steps to the process for requesting and then voting via mail—and despite Alito’s good faith guarantee, the actual research shows that it’s voters of color, again, who are more likely to miss these steps and get their votes disqualified.

Waller County is not ancient history. The same animus drives our politics today. What began as a white primary, a literacy test or a poll tax is now a litany of disproportionate burdens and inconveniences. The goal is the same, and the impact will profoundly reshape the meaning of representative democracy everywhere and for us all. What begins in Waller County—or in Maricopa County, Fulton County, or hundreds of other voting jurisdictions throughout the country, will not stay there. American democracy is the frog in the pot. And that whistle is the alarm that it’s boiling.

David Daley is the author of Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn't Count and Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy.