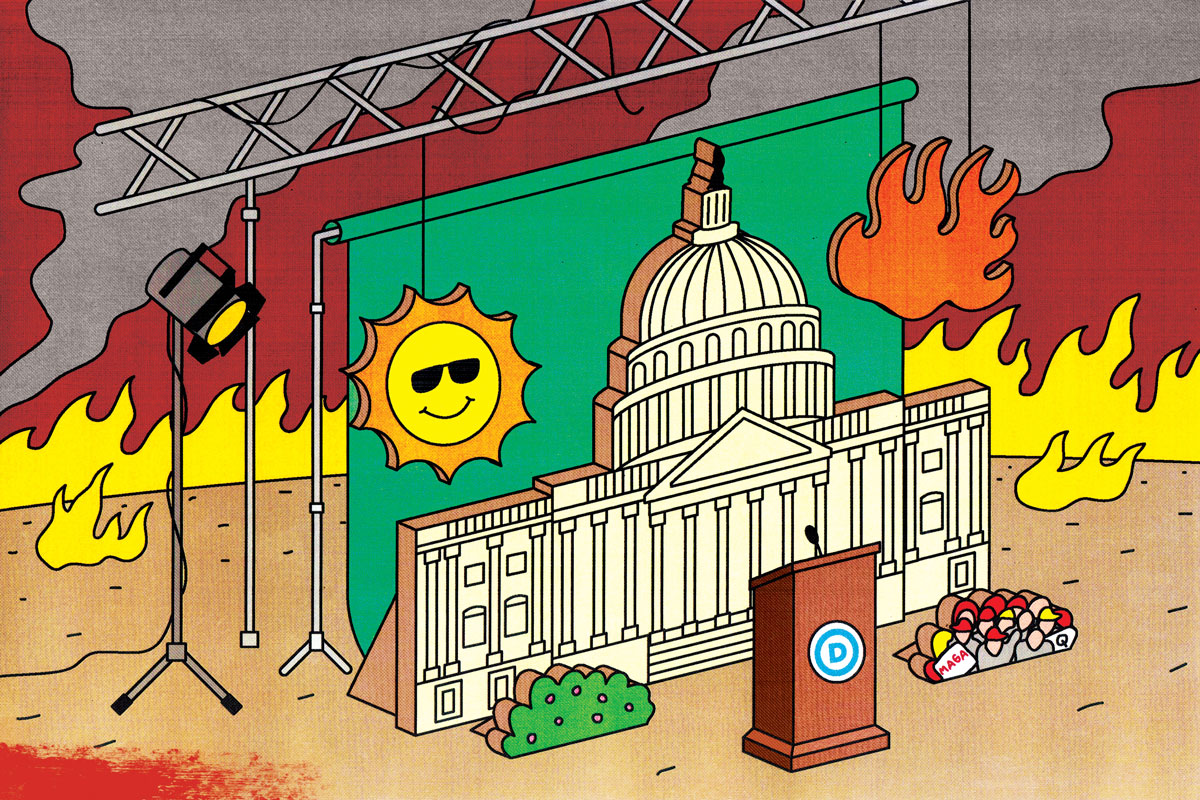

American democracy is imperiled on all sides—from baroque voter suppression schemes to the rise of the insurrectionist right to a Supreme Court in open ideological revolt. And the rhetoric of Democratic leadership strongly evokes this mood of crisis—at least half the time. The rough refrain goes something like this: This November is the most important election of our lifetimes. If the GOP returns to power, the future of democracy itself is at risk. As an individual, you are powerless to prevent this, but if you vote hard enough and donate even harder, we may just be able to avoid it—by the skin of our collective teeth.

Obviously, part of this appeal is tailored to maximizing fundraising returns, by stimulating the right nerve endings in the liberal-centrist electorate long enough to write a check to a congressional campaign committee. But the further you go up the hierarchy of party leadership, an odd disconnect begins to take hold: Yes, the future of our democracy is in jeopardy, but many of the best-known figures in the party are very far from the frontlines of this battle, and acting quite differently than their crisis-driven rhetoric suggests they might. Sometimes the small but potent imagery of moneyed detachment scrambles the messaging, as when House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was roundly derided after she took to the James Corden show in 2020 to showcase two refrigerators, one sporting a freezer stuffed with high-end ice cream.

At the very summit of Democratic power, this disconnect becomes almost blinding. Hillary Clinton—who ended her chronicle of the historic trauma of the 2016 presidential election with a breakdown of her self-care regimen—has recently published an airport thriller with potboiler impresario Louise Penny, steeped in fantasies of geopolitical payback for a thinly fictionalized Donald Trump. As for Clinton’s former Democratic primary rival and later White House boss, Barack Obama, he has brand extensions stretching across the vast reaches of the mediasphere—from coffee-table paeans to his bro-ship with Bruce Springsteen to Netflix documentaries on the national parks to his celebrated Spotify playlists and general displays of cultural and intellectual curation on Twitter.

Democratic leaders, from former presidents on down, can’t seem to decide whether everything is collapsing and our democracy is falling apart, or if everything is more or less normal and, provided everyone votes blue, basically fine.

To be sure, political figures in semi-retirement deserve their private lives, and whether the Obamas and the Clintons decide to devote themselves to public service or empty-calories entertainment or nothing at all is their right. But Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton are not actually ex-politicians. They have kept a toe on the playing field, so to speak, resurfacing every few months to deliver dire warnings about the health and prospects of our democracy, and how you—yes, you—are responsible for whatever happens to it.

And as we’ve noted, when prominent political figures like Obama and Clinton warn us that grim moments of antidemocratic reckoning may await us all, they are not lying. Yet the dissonance here—the ear-splitting clash between their words and the staggering banality of what they are currently doing with their lives—is difficult to miss. If things are as bleak as they claim, should they not be out on the proverbial barricade somewhere? They have access to any sort of platform they desire; their retirement (voluntary or otherwise) from elected office does not prevent them from mobilizing the large portion of the public that listens to them and holds them in high esteem.

I don’t know. I’ve never been in their shoes. But were I convinced the end is nigh, I don’t think I’d be writing topical thrillers or cultivating my renegade image with the Boss. I might try to use my enormous leverage over the discourse to produce something more substantial than published flights of Boomer fancy or potboiler payback.

If this seems like a petty gripe, it isn’t. It speaks to a larger problem—perhaps even the problem—with present Democratic messaging: Democratic leaders, from former presidents on down, can’t seem to decide whether everything is collapsing and our democracy is falling apart, or if everything is more or less normal and, provided everyone votes blue, basically fine. Is this an existential crisis for the United States or isn’t it? And if it is—an argument that has ample evidence to support it—why aren’t the people in charge acting like it?

It’s true that simple political theater plays a role in all this. There has always been a notable gap between the political stakes as high-ranking Democrats describe them to potential voters and the half-a-loaf, better-than-nothing approach that defines how they legislate and govern. Depending on our position on the life cycle, we have all lived through five or ten Most Important Elections in Our Lifetime by now. Yet in the rare opportunities afforded the Democratic Party to exercise power, the absence of urgency is hard to miss. What was the Obama presidency, after all, but an eight-year reminder that our institutions, our economic arrangements, our putative meritocracy, are all pretty much fine, provided the right people are put in charge of them? These people can’t seem to figure out, in short, if America is falling apart or if—forgive me—America is already great.

It shows. Leaders like Pelosi, Chuck Schumer, James Clyburn, Steny Hoyer, and President Joe Biden all whipsaw between optimism and pessimism, alarmism and soothing reassurances, bold promises and the “pragmatism” they forever insist imposes a low ceiling on political reality. Unable to choose between two conflicting messages and stick to their provisional position for very long, they do what is least likely to work: They deploy both messages, depending on the day, the mood, a crushing defeat they have just suffered—and what we can only assume is a complicated formula involving humidity and solar radiation. We never know from one minute to the next if the end is nigh or if the foundation beneath us is stable enough to permit some mindless diversion to shore up our morale.

Individual Americans can hardly be expected to maintain a constant state of vigilance and assume personal responsibility for the survival of the republic. But that posture is not in fact too much to ask of our elected officials. As the Supreme Court disassembles the twentieth century to pave the way for reinstating the nineteenth, neither the House nor the Senate is in anything that could be mistaken for crisis mode. The White House is only marginally more consistent in making sure its public-facing messaging campaigns radiate seriousness, although they regularly fall short of that mark too. While it is Politics 101 that the president should be spiking the football over what may be a deal with Emperor Manchin on substantial portions of his domestic policy agenda, Biden has long since fallen silent on crucial voting rights issues and has either resisted or downplayed much-needed pushes to reform the Senate and federal courts. The overall message can best be summed up as: Look, we can still make the institutions work. In a few years, we are likely to look back on that message as nothing more than a brief, pleasant thought experiment—bounded on both sides by overwhelming evidence that they do not.

As for emeritus figures like Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, they are fair game for criticism because they regularly choose to insert themselves in the political arena they’ve ostensibly left behind. They resurface every few months to tease un-retiring (in Hillary’s case) or to wag a finger (the former president’s favorite trick) at voters who threaten, once again, to fail their powerful leaders. You and I, people with no power and little-to-no influence over what anyone else thinks, can be forgiven for spending our days making widgets or sitting through interminable Zoom meetings or doing the thousands of other ultimately meaningless things we do to keep the rent paid and the fridge stocked. For those lucky enough to have a bigger megaphone—the power to do more—we have a right to set the bar a little higher.

Think of what the post-presidency of Jimmy Carter might have looked like if, instead of housing the homeless and battling the apartheid policies of the state of Israel, he went on tour with the Allman Brothers, or signed up to co-write a handful of script treatments with George Lucas.

Consider, for example, how the legacy of activist former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt would look today if, instead of campaigning for world peace, gender equality, and racial justice, she’d settled into a position as a panelist on “You Bet Your Life,” or a sideline as a literary collaborator with Erle Stanley Gardner—with occasional exhortations from her to keep voting Democratic lest the postwar world tumble into nuclear-age chaos. Or think of what the impressive post-presidency of Jimmy Carter might have looked like if, instead of housing the homeless and battling the apartheid policies of the state of Israel, he went on tour with the Allman Brothers, or signed up to co-write a handful of script treatments with George Lucas.

Perhaps, though, our Democratic leaders are neither complacent nor feckless. Perhaps they’re seeking to project a sense of nonchalant competence so as to reassure us that everything is under control. Here, two obvious objections present themselves. One is that their words do not match the serene absence of urgency that the workaday leaders of the Democratic caucus in Congress keep radiating. The other is that we have forty-plus years of indisputable evidence that the Democratic Party, with respect to holding back the excesses of the far right, very clearly does not have it all under control. They’ve been either outplayed by the GOP or too eager to abet the GOP over and over again, and for a long time.

The core problem, then, is not that they are deceiving voters when they claim that our current political moment is dire. The problem is that they seem utterly convinced that they are not simply part of the solution, but the solution, full stop. This garbled message comes across with dismaying clarity, even when many other elements of Democratic messaging don’t: Everything is a mess, but everything is also basically fine–provided you put us in charge.

That, fundamentally, is where the Democratic pitch, its de facto justification for the party’s existence, starts to crack under the strain. The percentage of Americans who really believe that things are basically fine is rapidly shrinking, and has been for a long time. The party arguing that so long as we put it in power things will be fine has no coherent or convincing explanation for why things continue to get worse, even when they are in power. They’re left to sell that message to the part of the electorate that both abhors right-wing ideology and is materially well-off enough to be safe from the worst consequences of our ongoing, slow-motion pratfall into managed democracy and white nationalism. There is no electoral math that makes that a viable long-term strategy.

The voters Democrats have been struggling to connect with or reliably bring to the voting booth do not see the status quo as “fine,” nor do they seem content with the usual pitch that perhaps the Democrats haven’t been great, but look at how much worse the Republicans are. (This, indeed, is the explicit takeaway of a new, Nathan Fielder-esque radio ad produced by the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee.) Messaging can only carry so much of the load, and ultimately what the party does or does not accomplish while in power will be the basis on which the electorate will judge it. Not every American is highly attuned to the day-to-day conduct of Washington politics. But it doesn’t take a political sophisticate to wonder if things are as dire as they seem for our democracy if their senators can take the next few weeks off, and if some of the most visible figures in American liberalism don’t seem concerned enough to interrupt their production schedules.

Ed Burmila is the author of Chaotic Neutral: How the Democrats Lost Their Soul in the Center (Bold Type Books).