The result of the runoff election between incumbent Georgia Democratic Senator Raphael Warnock and Republican Herschel Walker will determine whether or not Democrats retain true control of the Senate. If Democrats win an additional seat, it will allow the party to appoint committees in its favor and potentially allow easier confirmation of judicial nominees. As centrist Democratic senators Joe Manchin and Kristen Sinema thwarted the Democrat’s attempt to end the filibuster, having an additional liberal Democrat in Warnock could prove to helpful in the future. In a plurality election, an election in which the winner of an election is the candidate that received the highest number of votes, the most common in the United States, Warnock would have already won. In the 2022 general election, Warnock received 49 percent while Walker received 48 percent.

Runoffs—an election triggered when a candidate does not earn 50 percent or majority of votes cast. While ten states mandate a runoff election if candidates do not win a majority in their political party’s primary election, Georgia and Louisiana are the only states that require a runoff election if candidates in a general election do receive majority of the vote.

Runoff elections have a deep history in the peach state’s politics that is tethered to conservative attempts to disenfranchise Black votes and Black candidates. Warnock and the Democratic Party of Georgia filed a lawsuit to reverse a 2021 law that forbids early voting on the second Saturday before a runoff if the preceding Thursday or Friday are state holidays. The Thursday and Friday that were question were Thanksgiving and a “State Holiday” created to commemorate Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s birthday.

It seems fitting in America that a voter suppression law passed as backlash to the defeat of Donald Trump, a white supremacist, was weaponized to prevent Georgia’s electorate from voting early in runoffs, a form of election championed by a segregationist, because of the commemoration of an enslaver, who was against Black suffrage. Runoffs in tandem with the state’s veneration of Robert E. Lee are signposts that Georgia elections are still conduits for preserving the power and interest of Georgia’s white electorate. Indeed, this year’s showdown between two Black candidates retains features of every era in the state’s long history of white backlash to Black suffrage.

Shortly after the death of Robert E. Lee in 1870, the Georgia general assembly passed a resolution for a day to “be observed by the people of the commonwealth as a day of solemn mourning for this public calamity.” Lee opposed granting Black Americans voting rights, writing that Blacks “could not vote intelligently,” and Black suffrage would “excite unfriendly feelings between the two races.” In 1889, the 90th Georgia General Assembly passed an act to make Jan. 19, Robert E. Lee’s birthday, a public holiday. In a July 2014 memo, Nathan Deal, Georgia’s Republican governor, moved the observance of Lee’s birthday from Jan. 19, to late November. A year later, Deal removed Lee’s name from the holiday, renaming the day a “state holiday” yet preserving Lee’s birthday as the date that marks the holiday.

Deal’s renaming Robert E. Lee Day to “state holiday” did not a change its spirit. “It’s hopefully a good faith effort on the part of state government to lower the degree of debate and discussion, and to show that we are a state that has come a very long way,” Deal said, “We are tolerant of a lot of things. But we will also protect our heritage. But this was not one of those areas area where I thought it was necessary to keep those labels associated with the holiday.” Later, Brian Robinson, spokesman for Deal, confirmed Georgia still intends to celebrate Robert E. Lee day even if it does not explicitly celebrate it by name. “There will be a state holiday on that day,” Robinson said. “Those so inclined can observe Confederate Memorial Day and remember those who died in that conflict.”

This year’s showdown between two Black candidates retains features of every era in the state’s long history of white backlash to Black suffrage.

The defeated Confederacy always valorized itself through redemption narratives. Herschel Walker does not evoke these narratives of the Confederate States of America by name, but conjures them in spirit. “He [Raphael Warnock] makes statements like America: the biggest problem with them is racism,” Walker said in a recent Fox News segment. “Why don’t he get out of racism and learn redemption, learn forgiveness, learn to move on and make this country better.” Walker’s suggestion that Warnock “get out” from racism makes sense because Walker is the beneficiary of it and without its labor, Walker would not have a political life. Walker is clearly the choice amongst white Republican voters, winning 70 percent of the white vote according to exit polls from the November 8 election.

That Walker himself is Black does not make winning the majority of white voters a paradox or contradiction. Walker’s campaign is aligned with a Trumpist Republican Party that embraces white supremacy, welcomes domestic violence, shuns intellect, and advances unfounded claims of voter fraud. Walker’s own debauchery befits a Republican Party that is controlled by a demagogue who advises that men grab women “by the pussy,” and declares he can “stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody” and not lose votes.

If Walker had no political utility amongst Republicans, his criminal behavior would be used as an example of Black pathology, feeding their carefully maintained stigma of Black masculinity gone awry. Georgia’s Republican voters are supporting Walker because he was anointed by Trump, a blessing that permits Republican voters to vote for a candidate that otherwise represents their greatest fears: a dumb, brutish, violent Black man. In the eyes of Trump and his loyalists, Black pathology can be—if not cured—tolerated, so long as the perpetrator serves the goals of white supremacy. Through osmosis of the assumed innocence of whiteness, Walker is granted “redemption” from this pathology, but not before he loudly denies American’s racism and becomes complicit in his party’s attempts to thwart the vote. White redemption requires Black disenfranchisement.

Georgia was readmitted into the union after ratifying its 1865 state constitution. To comply with the federal mandates of Reconstruction, a Georgia Constitutional Convention was held from Dec. 9, 1867 to March 1868 with some 33 African American and 137 white delegates. The federally sanctioned convention drafted a new Constitution that forbade disenfranchisement and guaranteed suffrage for Black males. The new Constitution also abolished imprisonment for debt and eliminated poll taxes—practices that exploited formerly enslaved Blacks. Conservatives lamented the “negro-radical” convention because it threatened to grant Black Americans equal status to white men. The elections following the 1868 Constitution yielded the “original 33,” the first 33 Black men to be elected to Georgia’s general state assembly. The victory was short lived. In August of that year, white Democrats proposed a resolution to deny Black men eligibility to serve in Georgia’s state legislature. The legally elected Black representatives were expelled and replaced with white men.

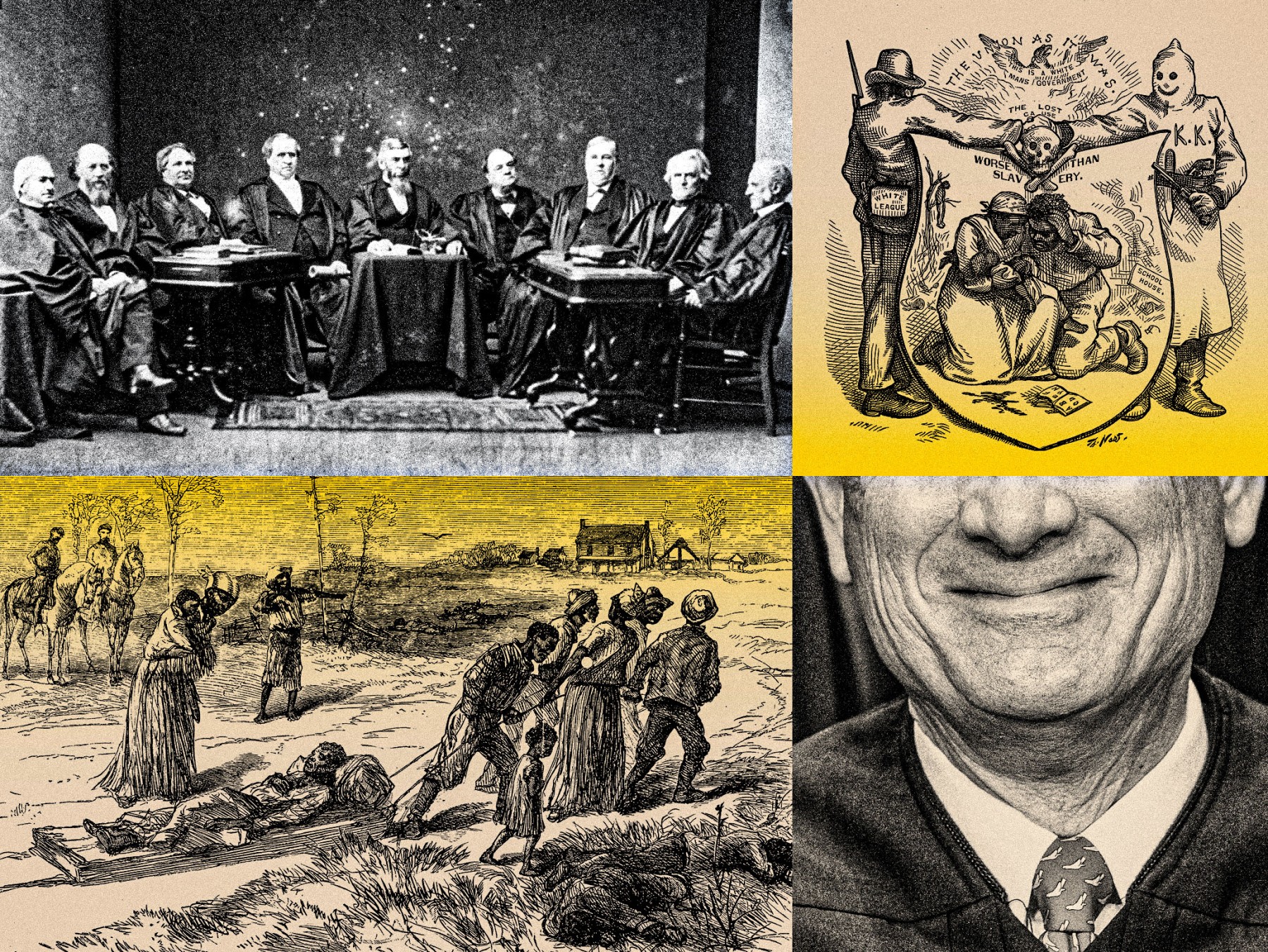

Though the expulsion was ultimately ruled unconstitutional, white supremacists would continue to attempt to disenfranchise Black Americans. Democrats had regained control of many southern states by 1870, making several, including Georgia, one-party legislatures. Georgia’s 1877 Constitution left the selection of the governor to the General Assembly, and barred Black Americans from voting in Democratic primaries, creating what were called “white primaries.” Other southern states did the same. It wasn’t until April 1946 that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that “white primaries” were unconstitutional. After the ruling, Black voter registration increased from approximately 20,000 in 1940 to 125,000 in 1947.

White redemption requires Black disenfranchisement.

In 1917, the Georgia legislature adopted the county unit system for all primary elections. Instead of “one man, one vote,” the county unit system was a statewide electoral college that gave smaller rural counties, which were mainly white, control over selecting the state legislature. This sham structure in Georgia’s faux Democracy would set the stage for these small counties to hold a monopoly on political power in Georgia that continues to this day. Georgia’s 159 counties were divided into three categories: The eight most populated counties were designated as “urban” and were given six unit votes each. Each of the next thirty populated counties or “towns” were given four unit votes, and the 121 remaining “rural” counties were given two unit votes. The candidate who received the most popular votes in a county received all of that county’s unit votes. The county unit system meant that the 121 rural counties held 59 percent of the overall vote and had the power to decide the state legislature. Because Georgia was virtually a one-party state—the Republican party was not even considered a contender—general elections were decided at the primary stage.

In 1950, 1,312,666 whites lived in Georgia’s rural counties compared to 572,465 nonwhites. In total, there were 37 counties in which more than 50 percent of the population was Black. Out of the 121 rural counties, 101 of those counties had less than 40 percent Black population. Under the county unit system, urban voters were still captive to the political will of white rural voters. Georgia’s 1946 gubernatorial primary election proved the county unit system efficacy in maintaining white supremacy in spite of the increase Black voter registration.

The primary that year was a vital election. Eugene Talmadge a corrupt, racist segregationist, who was lauded as the “the white people’s candidate” in his race against moderate James Carmichael. “If the white citizens of the State of Georgia will wake up,” Talmadge said to the Statesman, a political newspaper, “they can disqualify and mark off the voters’ list three-fourths of the Negro vote in this state.” Talmadge was evoking a provision that allowed any citizen to challenge the voting right of a registered voter if they suspected the voter was not qualified. Black voters proved to be instrumental, yet the discriminatory forces of the county unit system were insurmountable. Carmichael won the popular vote (313,380 to 297, 245), but the county unit system gave Talmadge the election.

This kind of antidemocratic sleight of hand is still evident in Georgia politics today. Warnock won the popular vote in the 2022 midterm elections. Yet, a trend remains: Warnock won seven of the ten counties that cast the most votes, many of which are the same counties Carmichael won during the 1946 primary—the same counties that were historically disenfranchised by the county unit system. Of the ten counties the cast the lowest number of votes, mainly the sparsely populated counties that benefited from the county unit system, six went to Walker.

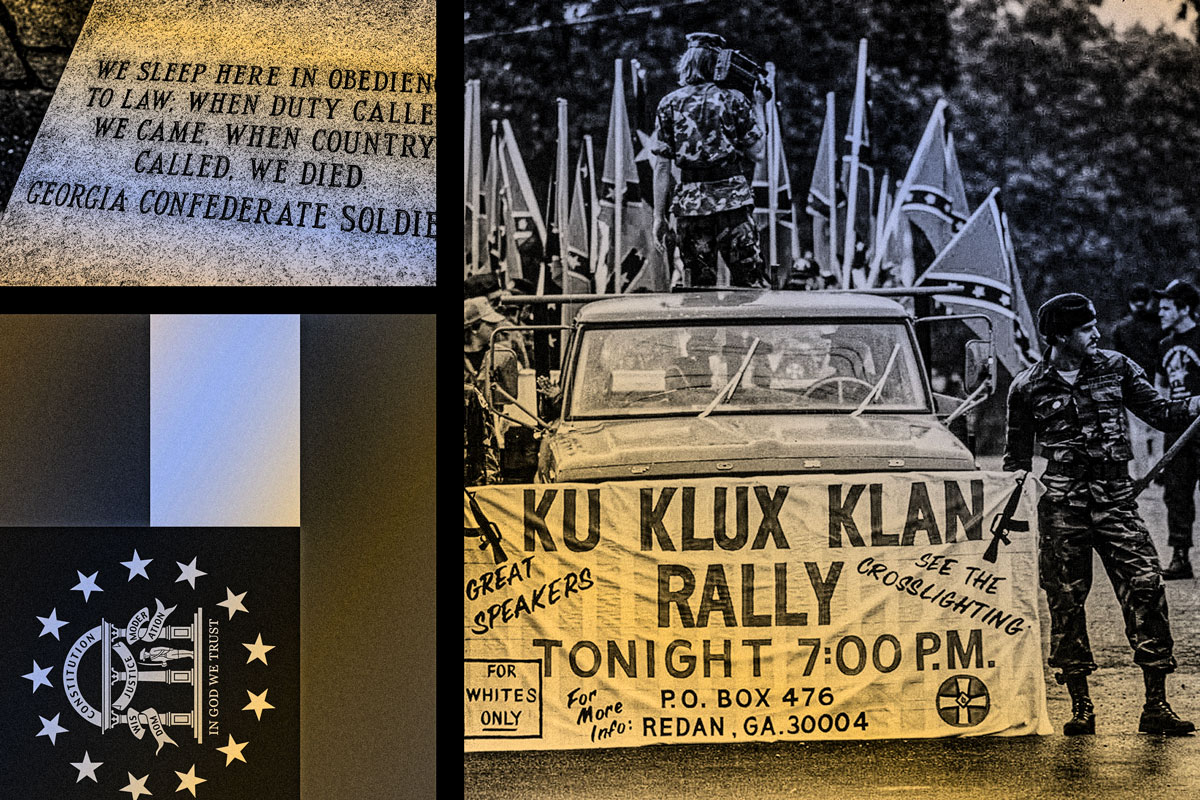

In 1953, Denmark Groover, a segregationist who supported including the Confederate battle emblem on Georgia’s state flag, proposed legislation to make runoffs part of all elections in Georgia. Groover’s bill would have required a majority vote in all state and local elections and require a runoff when no candidate received a majority of the votes. Groover proposed the bill days before an election in which a Black candidate was running for alderman against three white men, though he said his bill was not aimed at preventing Black candidates from holding office.

As a 1953 article in the Macon News pointed out, the overall effect of runoffs would be a foregone conclusion. “What will happen is obvious. If the white vote is split between several white candidates and a colored candidate is high man but not the winner by majority, the white vote will support the runner-up white candidate in the runoff and elect him over the Negro.” Marvin Griffin won the Democratic Primary in 1954. Griffin, a “white people’s candidate,” ran for governor with the endorsement of then-governor Herman Talmadge, son of Eugene Talmadge (who had died shortly after his 1946 victory). As the Associated Press said, Griffin’s regime would continue the “white supremacy championship,” Talmadge had established. Griffin ran on the “race issue,” advocating for Herman Talmadge’s proposed state constitution amendment to abolish public schooling to prevent integration. Griffin attacked his opponents and the NAACP for opposing segregation and the county unit system, and accused other Democratic candidates of attempting to “split the white people’s vote.”

In the 1958 elections, Denmark Groover asked for a recount of “negro votes” after his loss to J. Taylor Phillips, arguing that

My sole purpose in asking for a recount is a verification in order to protect the votes of the solid majority boxes against bloc voting in other boxes. I had a majority of over 1,700 in white ballot boxes. There was an obvious defect in one of the Negro boxes. I am unwilling for that 1,700 majority to have their votes destroyed without a proper recount and recheck of the block voting. On September 13, 1958, in “Ballot Recount Sustains Phillips Victory In Race,” the Macon Telegraph, reported that the error ended up being in a white precinct. “Officials found that figures from 79 of the county’s 80 voting machines were correct as originally recorded. The error was found on a white precinct machine from the Vineville 1 District. The results from the recount gave Phillips a 188 vote win over Groover instead of a 189 vote victory.”

The defect in question was a machine that gave a candidate 306 votes even though its voter counter showed that only 256 persons had voted on it. According to the Macon Telegraph, the return showed that Phillips led Groover by an approximately five-to-one margin in Black votes—2,027 votes ballots to Groover’s 397. Groover led Phillips in white votes 8,852 white votes to Phillip’s 7,411. Groover’s animus toward Black “bloc voting” was clear and unwavering, as he would spend the next decade championing the destruction of it. “In view of the substantial majority of white votes which I received I felt that that majority was entitled to a verification of the count in order, if possible, to keep bloc voting from controlling an election,” Groover said.

The runoff system became the last best hope of white supremacists fighting for electoral redemption of the Confederate cause.

In 1984, Groover summarized his racial views and politics as “reactionary.” “I was a segregationist. I was a county unit man… And I was raised in a county and I had many prejudices, and I don’t mind admitting it… If you want to establish that some of my political activity was racially motivated, it was… It would have been a major miracle, or taken a modern case of absolute blindness, for Blacks to have supported me in 1958.”

Black voters indeed rejected Groover en masse, and, in June 1960, superior court judge Oscar Long charged a Bibb County Grand Jury to “leave no stone unturned” in an investigation of “Negro bloc voting.” Long instructed the grand jury to “investigate and examine into the facts of every election of eerie kind in this [Bibb county] for the past several years in which bloc voting is apparent.” Long’s instruction said that Black bloc voting “strikes at the very foundation of our government and will ultimately destroy it if permitted to continue unabated.” As J. Morgan Kousser writes in his 2000 book Colorblind Justice, Long “ignored polarized white voting and Black disfranchisement entirely. Acting under the umbrella of a universally violated law that prohibited any payments to election canvassers, which Long himself had broken during his own election campaigns.”

The racist and totalitarian nature of Long’s mission was exemplified when Bibb County Sheriff James Wood was sentenced on three counts of contempt of court because of statements he made about the grand jury investigation. Judge A. M. Anderson sentenced Wood to 60 days in jail and a 600 dollar fine for each count. Anderson said Wood attempted to “cause rebellion against the court.” Woods challenged the judge’s use of the term “negro bloc voting,” saying the phrase is a political campaign watchword and had no place in “judicial charge.” He accused the Superior Court judge of using “the style and language of a race-baiting candidate for public office.”

The Bibb County grand jury ended the probe in July without any indictments, perhaps because of the jury’s findings that white officials actually violated the laws they were investigating.

The U.S. Supreme Court finally ruled the county unit system unconstitutional in Gray v. Sanders in 1963. The Georgia Democratic party held a “winner take all” primary election in 1962. The main contestants were Carl Sanders, a moderate Democrat who supported segregation but opposed interference with federal mandates for integration, and Marvin Griffin, a staunch segregationist. Now that a straight majority was not required and candidates could win on a plurality, Griffin, backed by the Klu Klux Klan, pinned his hopes on winning the 1962 gubernatorial election on the support of “Georgia’s white population.” “I must win this race with the white folks,” Griffin said. Griffin’s hopes were never realized, and Sanders won the popular vote.

The runoff system became the last best hope of white supremacists fighting for electoral redemption of the Confederate cause.

In a legislative battle that lasted ten years, Groover pushed his runoff bill through the House and in 1963 and persuaded the Senate Rules Committee to consider the bill. He didn’t mince words about his intentions, saying the bill would “stop this putting two or three men in the race to split the vote.” It was nearly twenty years since splitting the vote had nearly cost Eugene Talmadge his reign as a white supremacist governor. “We have a situation when the federal government intercedes to increase the registration of Negro voters,” Groover said. “One-third of the Negroes in my county will not vote without an endorsement sheet gotten up the night before. It would be true of any other bloc vote group, regardless of race or color.”

Runoffs were codified in Georgia’s constitution after the near-defeat of segregationist Lester Maddox in Georgia’s 1966 gubernational election. During the Democratic primaries, Maddox lost the primary lost the popular vote to Ellis Arnall, a liberal Democrat, but neither candidate crossed the majority threshold, so the race resulted in a runoff. After winning the Democratic Primary in a runoff election, Maddox faced conservative Republican Howard “Bo” Callaway. A number of Georgian voters, not impressed by either candidate, wrote in former governor Ellis Arnall as a protest vote. Arnall received enough votes to prevent Maddox or Callaway from earning the majority vote necessary to win. The result of the election triggered the state’s mandate that gave the General Assembly the authority to choose the winner.

Georgia’s legislature was controlled by Democrats, which gave them the advantage in choosing the governor. On November 17, 1966, a three-judge district in Georgia forbid the General Assembly from selecting the governor. That Court’s decision that a malapportioned Georgia legislature cannot select the Governor of the state was overturned in December by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Democrat-controlled Georgia legislature quickly swore Maddox in. Two years later, the Georgia Gubernatorial Runoff Elections Amendment appeared on the ballot and passed. James MacKay, a member of the Georgia House in 1963, stated in a court filing, “I do not think that the statewide majority vote requirements would have been passed had [House] members not been convinced of the racially discriminatory potential of the runoff system.”

In 1990, twenty-seven Black voters from Georgia challenged the majority-vote requirement for primary elections in Brooks v. Miller. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia dismissed the plaintiff’s claims that majority-vote requirements violate section 2 of the 1982 Voting Rights Act, claiming that the majority-vote requirement was not enacted for a discriminatory purpose and that it did not have significant adverse impacts on Black voters or candidates. The Eleventh Circuit panel reviewed the plaintiffs’ appeal and affirmed the district court’s ruling.

In spite of the court’s findings, it would appear that Groover’s bill achieved its white supremacist goal in a majority of cases.

The ruling was influenced in part by the State of Georgia’s expert witness, who presented the court with findings of a study on the majority-vote requirement’s impact on Georgia’s primary elections from 1970 to 1995. The study included around 2,800 runoff “sequences,” and documented 278 runoffs where an African American candidate ran against a white candidate. 85 of the 278 runoffs resulted in a “flip sequence,” a result in which the candidate who won a plurality of votes in the initial primary lost in the runoff. The Black candidate lost the runoff election in 56 of the flip sequences. The white candidate lost in 29. In spite of the court’s findings, it would appear that Groover’s bill achieved its white supremacist goal in a majority of cases.

Warnock’s victory over Republican Kelly Loeffler in 2020 special election is an example of an election without a flip sequence. Warnock won 32 percent of the votes to Loeffler’s 25 percent, which triggered a runoff election in which Warnock won 51 percent of the vote to Loeffler’s 49 percent. Warnock won 93 percent of the Black vote while Loeffler won 71 percent of the white vote, nearly the same as Walker’s margin (72 percent of the white vote) in the November 8 election.

As Graham Paul Goldberg writes in a 2020 Georgia Law Review article titled “Georgia’s Runoff Election System Has Run Its Course,” “The Brooks challengers failed to carry their burden of proof at a time when Georgia’s Democratic Party was far more white and less diverse than it is today.” In order for the plaintiffs in Brooks v. Miller to be successful, they would have needed to prove that the “political process[es] leading to nomination… are not equally open to participation by members of a class of [protected] citizens… in that its members have less opportunity than other members of the electorate to participate in the political process and to elect representatives of their choice.”

It’s hard to fathom how the courts ruled in favor of the majority-vote requirements given Georgia’s history. Yet, it is that same history that helps understand the court’s conclusion. The data they considered, of course, didn’t address Black candidates running against other Black candidates, and Warnock is the first Black American to represent Georgia in the Senate. But his own identity notwithstanding, Walker’s reactionary position against race-consciousness echoes the segregationists’ arguments against “bloc voting” by the Black population. “Why don’t he get out of [discussing] racism and learn redemption, learn forgiveness, learn to move on and make this country better?” Walker asked in the Fox segment. The context for this question isn’t just that Walker’s Trumpist, white supremacist backers have little interest in the urgent concerns of Black voters. It’s evidence of their cynical knowledge that any potential for their candidate’s success, and for conservative control of Georgia’s U.S. Senate seats, relies on a centuries-old strategy of Black disenfranchisement they’d rather everyone would just not talk about.

Anthony Conwright is a writer and AAPF fellow living in New York City. Follow him on Twitter @aeconwright.