The Supreme Court is so petty.

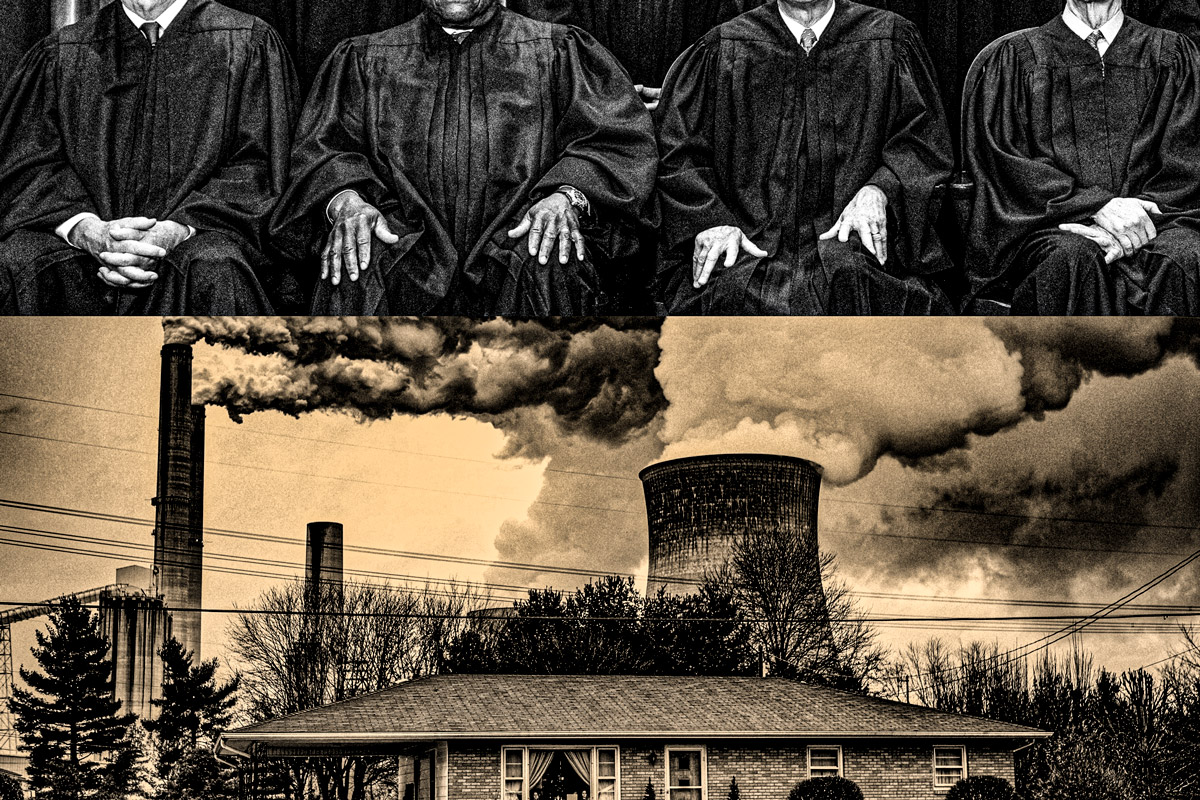

Consider the last major decision handed down during the high court’s ruinous 2021-2022 term. In West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS) unceremoniously stripped the ability of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to create and implement rules that regulate carbon and other climate-warming emissions, particularly from power plants. Citing a bogus and fringe constitutional doctrine of “major questions,” SCOTUS made this decision as, internationally, all of the respectable institutional alarms have been rung ad nauseam calling for countries—especially wealthy nations like the United States—to relinquish their greedy, corporate-driven dependence on fossil fuels. No other course of action holds any realistic hope of meeting global climate goals and saving humanity and Earth from climate disaster.

For people and the planet, this is all bad, and the Supreme Court, which at one time was an ally to Black Americans, is now an engine of hard-right policy-making denying basic civil and human rights. But what’s especially petty about this decision is that the Obama-era rules called into question by this case, West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency, never even went into effect. So why weigh in?

The answer is both a saga of shifting regulatory mandates and high-stakes policy making that has disproportionately harmed Black Americans—and will continue to do so. The regulatory story started back in August 2015, when then President Barack Obama, via the EPA, announced the Clean Power Plan (CPP), an offshoot of the Clean Air Act that would provide flexible guidance to states on how they could reduce greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. A prior 2007 SCOTUS case, Massachusetts v. EPA, had determined that the Clean Air Act did delegate the EPA authority to regulate greenhouse gases to meet the aims of the law—to regulate air emissions from stationary and mobile sources, to regulate emissions of hazardous air pollutants, and to protect public health and public welfare.

This Supreme Court, with a new far right majority, was more than ready and willing to test the bounds of its own authority; checks and balances be damned.

In the face of an obstructionist, gridlocked Congress, Obama chose to use both his bully pulpit and the might of federal regulatory authority to make national progress on an international problem. Remember this.

Under CPP, the EPA would provide to all regulated states their emissions goals, and states, in turn, would provide to the EPA their own unique plan by 2018 for how they would reach those goals and begin implementation by 2022. Maybe that meant transitioning their dirty coal-fired power plants to fossil gas, nuclear or, even better, renewable energy-powered plants and farms. Maybe states would set new codes and standards and invest heavily in energy and other building efficiencies across residential, commercial, and industrial sectors. Or maybe they could implement their own market-based mechanisms, such as state carbon taxes or carbon market schemes such as cap-and-trade or cap-and-invest, to drive down emissions. The possibilities and opportunities were wide—and, if all else failed, the states could defer to the EPA to provide them a plan.

At that time, the Obama administration estimated that if the Clean Power Plan was fully in place, by 2030, carbon emissions and pollution from the power sector would fall 32 percent below 2005 levels. This set of policy targets explains, in turn, why President Joe Biden is compelled to promise big wins today, even if they may just be soundbites, on the climate front—as in his recent pledge to achieve a 50-52 percent reduction from 2005 levels in carbon emissions and pollution by 2030. Due to the urging of environmental and climate organizers and advocates, the Biden administration is trying to make up for the invaluable time—decades—squandered by our nation’s leaders.

Not even two weeks after the final rule was published in 2015, West Virginia, along with 23 other states filed lawsuits with the D.C. Circuit Court against the EPA. Their complaint alleged that the agency lacked the legal authority to require states to cut their carbon emissions. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce and other business trade associations filed additional suits pursuing the same general line of argument.

Even though 18 other states, together with some counties and municipalities, backed the new rule, the Supreme Court blocked the implementation of the CPP pending the ruling on West Virginia v. EPA by the D.C. Circuit. The D.C. Circuit began to hear oral arguments, but with the election of ardent climate change-denialist Donald Trump to the presidency in November 2016, the court agreed to suspend proceedings. Eventually the court dismissed the case, leaving the Trump-era EPA to chart its own plan of action.

The Trump administration took it upon itself to declare that, contrary to the precedent set in Massachusetts v. EPA, the Environmental Protection Agency did not have the authority under the Clean Air Act to regulate carbon emissions within and across states; instead, the EPA was only empowered to oversee the actions of individual power plants up to their fence lines, and on a case-by-case basis. The Trump EPA withdrew the Clean Power Plan in 2017 and released its own rule—the Affordable Clean Energy (ACE) Rule—in 2019. This measure sparked its own regulatory and legal controversy, drawing lawsuits from 21 Democratic-led states along with cities and environmental and public health organizations. (It is worth noting that in this same timeframe between 2017-2020, with a largely Republican-led Congress, Trump appointed three far right conservatives to the Supreme Court—Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett.)

In one of these suits, American Lung Association (ALA) v. EPA, the D.C. Circuit struck down the ACE Rule in January 2021. This decision found that the proposed Trump rule was “arbitrary and capricious”—and completely ignored the EPA’s responsibility to monitor and regulate emissions. As a matter of policy, the question of executive-branch authority in climate policy was remanded back to the now Biden-led EPA.

Back in the hands of the Biden administration, the EPA was left to figure out a new strategy to reduce carbon emissions and co-pollutants. And, with what would eventually reveal itself to be a wholly disappointing, do-nothing Democratic-led Congress as his tag team partner, President Biden was determined to redeem the United States as a major player in the fight against climate change on the global stage. The Biden EPA reaffirmed in a 2021 federal judicial filing that it did in fact have a mandate to regulate emissions from power plants, but also stipulated that it would not resurrect the Clean Power Plan. Instead, EPA officials testified that they would “consider the question afresh” and, taking the best elements of the CPP, ACE, and recent research and findings, craft a brand new plan that would pass judicial muster. This is pretty much standard operating procedure for federal regulators, especially with changing administrations.

But this is where things get weird.

Before any such new plan or guidance surfaced from the Biden EPA, West Virginia and other Republican-led states asked the conservative and libertarian-stacked SCOTUS to take up and reconsider the D.C. Circuit’s decision on ALA v. EPA. From a legal standpoint, it was far from clear how this challenge should proceed. With both the Clean Power Plan and the Affordable Clean Energy rule null and void and the Biden-led EPA moving on to new strategies, what exactly would SCOTUS hear and deliberate on?

Traditionally, SCOTUS deliberates on legal questions arising from what’s already written and codified, leaving hypothetical and philosophical speculations to Congress and state legislatures. It’s exceedingly rare—abnormal really—for the high court to hear cases where no specific active law or rule is in question. But this Supreme Court, with a new far right majority, was more than ready and willing to test the bounds of its own authority; checks and balances be damned.

The harmful effects of carbon emissions and their accompanying co-pollutants—including ozone, particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, sulfur oxides, volatile organic compounds, lead and other air toxics—are not felt equally among the American populace. Like most other facets of American life, environmental harm breaks down starkly along racial lines.

Black Americans, regardless of income or region, are more likely to be exposed to particulate matter. Black Americans also have higher rates of respiratory, cardiovascular, and metabolic diseases, and suffer higher mortality rates due to air pollutants. Other people of color experience similar poor health and life outcomes, too.

The same racialized pattern of harm holds for the health and environmental hazards associated with the extraction and processing of fossil fuels—coal, oil and gas. These dirty carbon-intensive industries all emit a number of hazardous co-pollutants, including carcinogens such as benzene and endocrine disruptors, that lead to increased rates of a variety of cancers as well as pregnancy complications such as stillbirths, miscarriages, male and female infertility and preterm births. What some call “fossil fuel racism” has wide implications; chiefly it forces the same communities of color already dealing with the toxic legacy of fossil fuels onto the front lines of swiftly rising and deadly climate impacts. To take just one example, dangerously rising temperatures have created extreme heat islands in urban areas that place Black, Latinx, Asian/Pacific Islander/Desi, Native American communities at disproportionate risk of heat stroke and premature death.

The high court has now positioned itself as the supra-regulatory arbiter of the EPA’s authority and, potentially, the authority of all federal agencies.

The negative health, labor and other socioeconomic impacts of the fossil fuel industry on communities of color are one key reason why so many organizations, particularly those focusing on racial justice and/or led by Black people, have been pushing administration after administration—and now the Biden administration and the Democratic-majority Congress—to phase out fossil fuels and enact a sustainable, just, and equitable transition expeditiously. It’s also why so many at the forefront of this struggle are rightly noting that there is no effective climate action without climate justice. And it’s why the verdict in West Virginia v. EPA is such a blow to the traditional federal regulatory solutions commonly relied upon for progress.

In line with the growing white nationalist and fascist tide that’s swept through both our government and our daily lives, threatening the foundations of American democracy, it’s not surprising that SCOTUS would be willing to hear the West Virginia v. EPA case, despite not having an actual rule or law to review.

To begin with, the six SCOTUS justices who made up the majority in the decision—Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, John Roberts, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett—are either members of or have known connections to the Federalist Society, a conservative-libertarian think tank devoted to returning the nation back to the original vision of the many slave-holding, wealthy white Founding Fathers of the 1700s. This vision also includes eager fealty to the patriarchal agenda of the founding era—holding essentially that women’s bodies are also ours to control, as witnessed in the disastrous ruling in the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling overturning Roe v. Wade and rescinding the constitutional right to bodily autonomy and reproductive freedom.

The Federalist Society is the original “Make America Great Again” crew. And one of the central goals of the Federalist Society is to restrict or remove the power of federal agencies to craft and enforce rules and regulations. So with SCOTUS captured by originalists, the West Virginia v. EPA case provided the Federalist Society clique, from the high court on down, the opportunity they have been looking for to strike at the authority of the EPA—a federal agency that has been purposefully underfunded, scapegoated and hamstrung by Republicans since the 1980s. (Starting with the mother of Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, who oversaw a wide-ranging agenda of regulatory demolition at the EPA when Ronald Reagan tapped her to head the agency in 1981.)

Traditionally, Congress assigns federal agencies a body of issues to manage or problems to resolve, and provides them broad authority to figure out and implement strategies and rules to achieve the policy goals set by Congress. Yet, driven by its own fallacious reasoning to adopt and apply the “major questions” doctrine, the high court has now positioned itself as the supra-regulatory arbiter of the EPA’s authority and, potentially, the authority of all federal agencies.

These checks and balances exist for a good reason—unlike Congress, agencies tend to be composed of public servants highly educated, trained, and experienced in the issue areas and related topics in which their agency has been authorized to regulate. But in its reading of the major questions doctrine—or more aptly in this context, the major rules doctrine—SCOTUS is now requiring Congress to provide federal agencies with an explicit, prescriptive “textual commitment of authority” to regulate issues involving major questions, especially when said questions may have “vast economic and political significance.”

With this new precedent now in place, the Supreme Court’s petty, forced decision on West Virginia v. EPA will have far-reaching implications beyond just the EPA. It will come to encompass the authority of any federal agency seeking to address increasingly complex, dire and pressing issues facing the nation—issues that, to any reasonable person, would fall under the purview of that agency.

Anyone would intuitively understand, for example, that the EPA is charged under its congressional charter to stop air pollution nationally. But that’s no longer the case in the “Upside-Down” that we’re presently living in, according to this version of SCOTUS.

The robust authorities of regulation and oversight assigned to the executive branch were supposed to be the Biden administration’s fail safe, serving the same function they did for his Democratic predecessor and former boss. But between Congress’s own self-inflicted legislative gridlock courtesy of the filibuster and the latest decision from what we may look back on and one day call MAGA-SCOTUS, Biden is running out of precious presidential time and options—especially if his only trick is to revive appeals to a white nationalist-captured Republican Party in the name of bipartisanship and compromise.

J. Ama Mantey, Ph.D. is a biomedical scientist turned policy professional and freelance writer. A proud two-time HBCU alumna, she writes about the social, cultural, and political implications and intersections of race, science, technology, public health and the environment.