When Congress moved to endorse long-overdue federal gun legislation this June, one of the only areas of bipartisan agreement concerned language to close up what’s known as the “boyfriend loophole.” This was the outgrowth of provisions in earlier gun legislation known as the Lautenberg amendment that sought to crack down on gun access for spouses in traditional marriages who had a history of domestic violence. Under the 1996 Domestic Violence Offender Gun ban, federal law has only placed a lifetime ban on individuals from purchasing firearms if they have been convicted of a domestic violence crime involving someone they’re married to, had children with, or shared an address with.

But as the phrase “boyfriend loophole” itself demonstrates, the reasoning behind the effort to secure tighter strictures on gun ownership against nonmarried intimate partners with domestic violence histories remains very much focused on traditional heteronormative partnerships. It’s true that most domestic violence cases involve male partners victimizing women, but this statistical imbalance means little to the many lesbian, gay, nonbinary, trans, and other members of nontraditional communities of sexual identification struggling with the immediate, and often mortal, threat of intimate-partner violence. Indeed, for decades now, the strongly heteronormative policy presumptions shaping domestic violence law have created a vast nontraditional loophole.

The new Safer Communities Act carries forward this tradition, even as it seeks to broaden restraints on gun ownership to include unmarried partners Under the pre-existing status quo, non-heteronormative partners victimized by domestic violence were largely invisible to lawmakers and law enforcement alike. The new expansion of the boyfriend loophole provision will include bans on the purchase of firearms for a span of five years for dating partners who have been convicted of domestic violence crimes.

For decades now, the strongly heteronormative policy presumptions shaping domestic violence law have created a vast nontraditional loophole.

However, the law supplies very little specific direction in adjudicating just what does and does not count as a “dating relationship.” This means it’s largely up to the discretion of the courts to assess the nature and length of a given relationship, as well as “the frequency and type of interaction” between the people involved, as stated in the law’s text.

Given that the federal courts are heavily stacked with conservative justices—and that even the recently won recognition of gay marriage may be in jeopardy under the Supreme Court’s hard-right majority—there’s little ground for thinking that judges will make compassionate or inclusive use of the wide discretionary powers granted to them under the Safer Communities Act. It’s far likelier that complainants in court interventions in domestic violence cases that involve nonheteronormative dating partners will be ostracized, scrutinized, and punished by the court officials—and by the legal system writ large. That will especially be the case for endangered partners who are Black or brown, and have abundantly well-founded reasons to distrust the courts and law enforcement. And this, in turn, makes it all the more difficult for such partners facing the threat of domestic violence to make use of any legal protections that might otherwise help secure their safety.

Of course, carceral responses to domestic violence are themselves deeply flawed. Research has shown that relying on court rulings, arrests, and criminal convictions to prevent domestic violence can actually make victims less safe. This is especially true for Black women and non-heteronormative citizens of color, who are disproportionately more likely to suffer from conditions like poverty and unemployment that make abuse more likely and harder to escape.

The consequences of this systemic neglect are deadly. The Everytown Gun Safety Support Fund reports that 73 percent of the transgender gun violence victims killed from 2017-2022 in the U.S. were Black women. Because existing domestic violence and gun laws don’t recognize many of the intimate partnerships for Black transgender women, it’s not clear how many of these killings were related to patterns of domestic violence in their homes—but any serious reckoning with this acute level of lethal anti-Black and anti-trans violence has to begin with the simple affirmation of their identities and potentially hazardous domestic situations.

During the same month that Congress ratified the Safer Communities Act, President Joe Biden signed an executive order advancing LGBTQIA+ equality directing the federal government to review and investigate barriers in accessing legal aid resources and other basic legal protections within nonheteronormative populations. “For LGBTQIA+ people who have faced family rejection and rely on family structures without legal recognition, marital, or blood ties, barriers in accessing federal resources can be particularly pronounced,” the order declared.

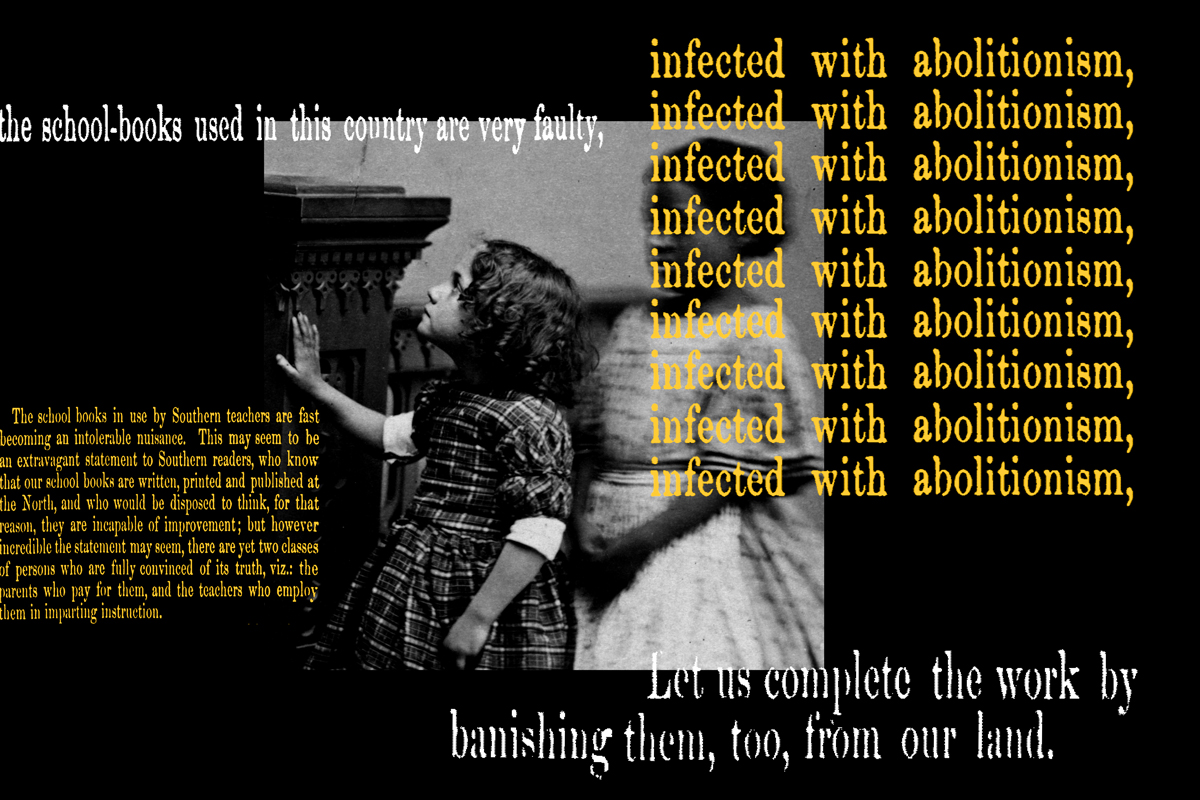

The new language in the Safer Communities Act is far more likely to complicate the realization of this federal mandate than to advance it. By relegating the authority to define and delineate the sorts of relationship that properly fall under the law’s provisions to the federal judiciary, the gun law will help resurrect old canons of stigmatization and endangerment sanctioned under heteropatriarchal law. The practice of breaking down romantic relations into elective patterns of length, duration, and frequency has reinforced the longstanding regime of carceral oppression that manipulates, discredits, and marks members of the LGBTQIA2S+ community as deviant and unworthy of justice when they’ve been victimized by domestic violence. To place this crucial power of definition in the hands of the federal judiciary means that our system of carceral justice would be empowered anew to serve as the ultimate arbiters of relationship legitimacy, livelihood, and life outcomes for nonheteronormative partners at risk of domestic violence.

Andi Boykins is a Black transgender woman and an outreach advocate at the Wanda Alston Foundation in Washington, D.C., and knows these risks firsthand. “In my previous dating relationship I faced all different kinds of abuse including verbal abuse, isolation abuse, identity abuse, and physical abuse,” she said. “My past partner still has a firearm until this day, and used that weapon as a sense of control and fear in the relationship against me.” Boykins also noted how systemic discrimination and stigmatization from the legal system compounded her sense of endangerment as a Black transgender woman. “I have had experiences in relationships where I would call and rely on the law, and police officers would arrive to the scene and make a mockery or joke because me and my partner are in a LGBTQIA2S+ relationship and treat the issue as if it is not serious or credible.”

Boykins also noted that the comparative laxity of the penalties on domestic violence perpetrators who are defined as “dating partners” in the new law’s language can produce ongoing and retraumatizing risk for people victimized by intimate partner gun violence. “Abusers come back with vengeance and retaliation,” Boykins said. “In my experience, every abuser I have had retaliated against me in different ways. If you are going to place lifetime bans on abusers from owning guns who are married, have kids, or live with their partners for doing the same thing as a boyfriend or dating partner, why is the punishment more lenient on the dating partners? Why is it not the same?”

She also notes that perpetrators of domestic violence on dating partners are allowed to continually re-create cycles of harm under the five-year gun restriction ban, since repeat offenders face no cumulative penalties, and are thus empowered to continue menacing and abusing their partners. “An abuser will think, ‘I abused my partner, I lose my rights to purchase a gun for five years, Five years are over, and I get my rights restored, then I go on to abuse the next person, Another five years pass, and I have my rights to purchase a gun again, and then the cycle continues.’”

This is all part of why Boykins regards the new boyfriend-loophole provision in the Safer Communities Act as a measure that sanctions status-quo systematic harms suffered disproportionately by Black nonheteronormative partners, while securing heightened legal protections for cisgendered, straight, and married citizens. “Institutionalized homophobia—that’s what it is when laws like this are set in place,” she said. Boykins argues that the boyfriend loophole language in the new gun law must acknowledge the full spectrum of sexualities, genders, and fluid relationships. “This law should be re-written to be accessible to individuals who are non-binary, lesbian, transgender, queer, asexaul ,intersex, and two-spirit,” Boykins said. All these communities “face domestic violence . . . in all types of relationships, including romantic, professional, and platonic,” she noted.

“Institutionalized homophobia—that’s what it is when laws like this are set in place.”

The disparities in punishment now encoded in the boyfriend loophole provision call to mind another deadly, and racially inflected loophole in federal gun law enforcement—the background check provision now known as the Charleston loophole. This is the enforcement gap that permits gun dealers to sell firearms before the FBI executes a full background check for the buyer under the National Instant Criminal Background Checks System. This was the loophole successfully exploited by Dylann Roof, the white supremacist gunman who massacred nine Black parishioners, most of them women, at the Emmanuel AME Church in Charleston, South Carolina in 2015.

The Charleston loophole is still unaddressed by federal law, but with the precedent of the boyfriend loophole provision before them, domestic violence victims like Andi Boykins say that they’re not hopeful that pleas for comprehensive and inclusive justice will prevail: “If they keep the loopholes open, the people they want to fall in them will continue to do so . . . I know what it is like to want to get the law involved and to be in situation where you feel like you have no choice, when survivors go to the call police there’s a risk of them being killed by a gun and the preparator threatening to kill themselves so they do not face the consequences of going to jail.”

Boykins encouraged Black partners who are at risk of domestic violence in nonheteronormative relationship to seek outreach resources and consult with grassroots nonprofit organizations dedicated to advocacy on their behalf. “A lot of times when survivors are abused during their upbring and nurturing stages of life in their childhoods, so when you become an adult and face abuse it almost becomes undetectable,” Boykins said. “As an outreach advocate for individuals who have faced domestic abuse . . . I connect survivors with counseling to get to root causes of enduring abuse, provide housing to individuals seeking to escape from abuse, and equip survivors with alternative coping mechanisms.”

The mandate to seek true restorative justice across the LBGQTIA+ community must be taken up beyond Congress, and by all cis and hetero allies seeking to reduce stigmatization, the epidemic of gun violence and legalized oppression. In the words of the Black feminist scholar Cathy J. Cohen, “at the intersection of oppression and resistance lies the radical potential of queerness to challenge and bring together all those deemed marginal and all those committed to liberatory politics.”

Denzell Brown is a Washington DC native and alumnus of Georgetown University. He is currently a doctoral student at Howard University conducting research focusing on post-traumatic growth outcomes, restoration-oriented coping mechanisms, and grief resolution methods that Black women use to heal after losing a child or loved one to gun violence.