Something unexpected happened in Pennsylvania politics recently. A leftist state senator got bi-partisan support from archconservatives in one of the most ideologically divided states in the country. Though the breakthrough didn’t happen in the arena of education policy, I think the story tells us what the defenders of public education can and should do in the face of so much reactionary toxicity from the right.

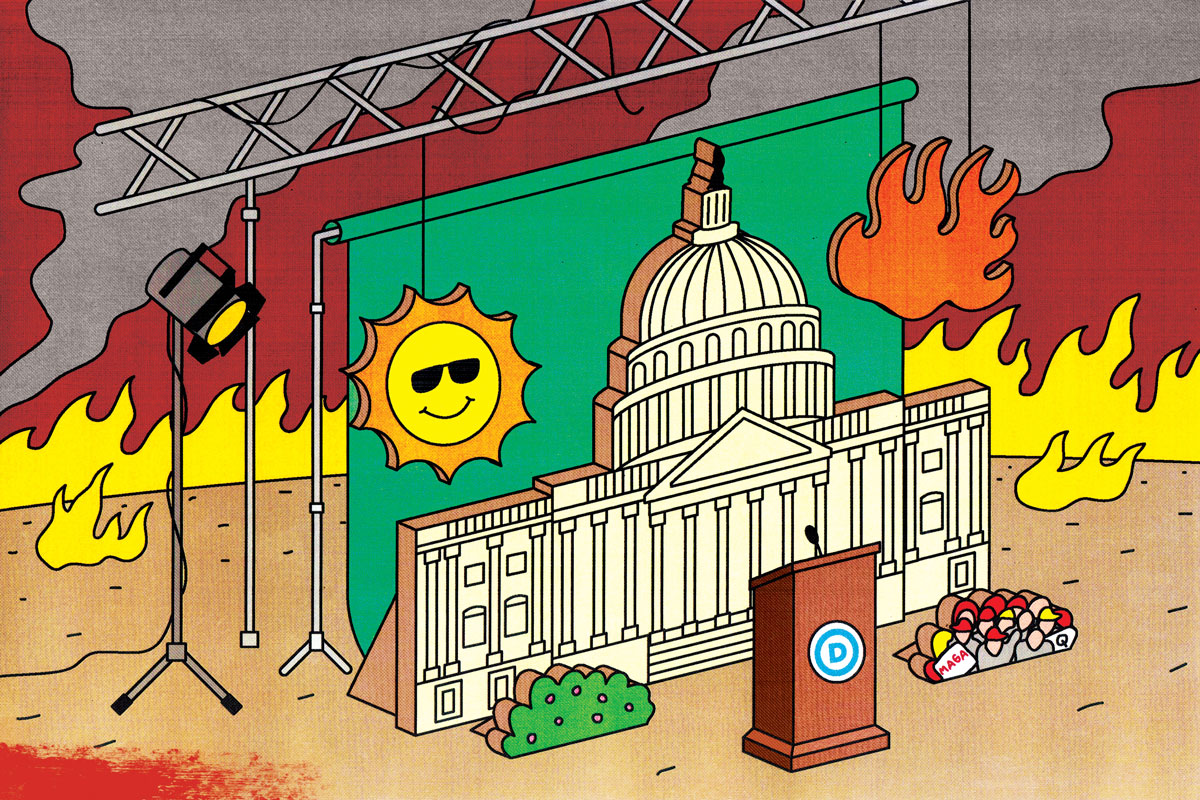

We know the toxin well by now. Scary sophist hack Chris Rufo is at it again, this time with a fabricated moral panic over the rampant adoption of “gender ideology” in schools. Ron DeSantis is dismantling Florida’s democratic government in Hungary’s image as he demands formal affidavits confirming the biological gender of public-school students. Meanwhile, the army of anti-CRT inquisitors affiliated with Moms for Liberty and other hard-right culture-war operations continue to menace the career of any school board member who dares support antiracism, or otherwise acknowledges the experience of most students in American public schools. Oh, and right-wing panic artists are trying to starve queer kids by arguing that Title IX provisions extended to LGBTQ students violate religious rights—and that schools found to be discriminating against these students should still receive food funding.

We’re at the end of the end of history and it’s a struggle. But there’s always something you can count on in a struggle: the possibility of fighting back and winning. And right now there are a great deal of ingenious and spirited approaches to fighting back that we can build on as the right keeps stoking phony culture-war outrage in the run-up to this year’s midterm elections.

Matt Bockenfield is one instructive case in point. When an anti-CRT bill was making its way through Indiana’s state senate, the teacher and union member asked one of the senators during testimony whether the idea of being “neutral” about history applied to the history of Nazism as well. The ensuing debate blew up the whole legislative effort. Similarly, the FREADom fighters are doing great work pushing back against feckless book bans and CRT crackdowns in Texas. The inimitable Jennifer Berkshire and Jack Schneider have also shown that, while the onslaught from the right is getting worse, its school board strategy is largely failing.

But we can’t rely on individuals or wait for the right to fail. What should an active, national, and coordinated response to these right-wing maneuvers be?

The overlapping anti-CRT and don’t-say-gay crusades on the right took up a great deal of media and political oxygen by changing the conversation, galvanizing support, and driving turnout at the local level with fabricated issues that appeared to resonate among conservatives. But now that this strategy is succumbing to distinct shortcomings and limitations, the defenders of public education on the left have an opening to counter with something constructive and liberating. Indeed, construction is a perfect issue to outshine the right—and that’s where the story from Pennsylvania comes in.

There are a great deal of ingenious and spirited approaches to fighting back that we can build on as the right keeps stoking phony culture-war outrage in the run-up to this year’s midterm elections.

In July, the Whole Home Repairs Act passed in the commonwealth’s General Assembly. The program, which received $125 million in state funding over the term of the most recent state budget, provides public resources to rebuild and fix up housing throughout the state. The politics of the WHRA’s passage were nothing short of remarkable. The legislation came out of progressive state senator Nikil Saval’s office. (Full disclosure: I helped write Saval’s school funding platform and voted for him.) But Democrats are in the minority in Pennsylvania, so how did Saval and his team do it? They were able to garner support from several top-ranking Republicans by focusing on the crumbling housing infrastructure in their districts.

For example, GOP state Sen. Dave Argall represents state senate district 29. Argall is the head of the powerful Government Committee and is very conservative. Yet blight has been a key issue for him. “You’re going to see blight in any town in Pennsylvania that has faced economic difficulty,” he said. “It doesn’t matter whether it’s big or small. If the coal mine closed, if the steel mill closed, if the major, important employer left town, that town is going to have some challenges.” Saval, a savvy politician, knew that home repairs would be a constructive issue that would resonate with people who aren’t supposed to agree with him on anything else. So Argall, along with other influential Republicans, fell into line, and the policy passed. I think this same kind of constructive politics could work in public education.

Could we change the terrain of this fight by focusing on fixing up and rebuilding all kids’ school buildings, across geographic, racial, economic, and cultural divides? In the same way that passing infrastructure legislation, industrial policy, and the climate agenda at the federal level has given Democrats something to beat back the supposed red wave of the midterms, perhaps the Democrats can develop innovative-yet-concrete ways to shore up the popular cause of public education.

Housing and schools are bound together in the United States. The largest sources of funding for public education are state and local tax revenues, the latter providing on average 45 percent of funds for public school districts (which still serve almost 90 percent of American school kids). This local funding comes from property taxes. So when you have towns with economic difficulties like the ones Argall mentions, the blight infecting housing infrastructure spreads to school infrastructure as well—particularly school buildings, which face their own crisis.

The blight in America’s school buildings is dire, actually. In 2021, the American Society of Civil Engineers’ (ASCE) Committee on America’s Infrastructure gave U.S. school buildings a D+. A 2020 study by the Government Accountability Office reported that 54 percent of schools need to update or replace multiple building systems. In 2011, the EPA estimated that 46 percent of schools had conditions contributing to poor environmental quality.

And like everything else having to do with life outcomes in America, these school infrastructure inequalities are racialized and class-inflected. This key insight has led scholars Erika Kitzmiller and Akira Drake Rodriguez to conclude that our schools are, according to the research literature, officially toxic—particularly for Black and brown students. These imperiled structures are more than just eyesores: school buildings significantly determine both health and learning outcomes for the students, teachers, and staff who work in them.

The school building blight is everywhere, including in Dave Argall’s district. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court is set to decide a school-funding lawsuit nearly a decade in the making. Within the case file for William Penn et al v. Pennsylvania Department of Education, there’s a litany of school-facilities horror stories across the commonwealth. One of the districts filing the lawsuit, Panther Valley, is in Argall’s area. As of 2014, the superintendent of the district testified that the elementary school is “in rough shape. It’s awful. It’s awful that our kids are in that kind of an environment.” The file continues:

The [elementary school] is “very old,” with cracks in the cement and an outdated roof that needs to be replaced and constantly leaks, creating water damage. In fact, Panther Valley teacher Tara Yuricheck testified that the roof has leaked since she first taught first grade in that building twelve years ago: “in my first grade classroom you could see the sky. There was a hole in the ceiling in my room that you could literally look up and see the sky.”

This isn’t what teachers and counselors mean when they say that the sky’s the limit for their students. The wheelchair ramp at Panther Valley Elementary is so cracked it can’t be used, but there’s not enough money to buy concrete and repave it. As of 2019, five years after the lawsuit was filed, all these things still needed to be fixed.

The same conditions prevail in a place that can feel like it’s on another planet than Panther Valley: Philadelphia. Not many things connect the two places like Panther Valley and Philadelphia. Panther Valley is 88 percent white and has just over 2,000 students total. Lansford, PA, where the school district is located, is very conservative in a county that is overwhelmingly conservative. Philadelphia, on the other hand, is 35 percent white and has 115,000 students. Democratic voters outnumber Republicans seven to one there. Philadelphia is an international city; Lansford is considered part of fly-over country. By most metrics, these two places are separated by all the political, economic, and cultural divisions the United States has to offer. But one big thing they share in common is crumbling school buildings.

Before school closures got national attention in the Covid-19 pandemic, Philadelphia was closing schools due to the abysmal condition of its school buildings: a veteran teacher’s cancer was attributed to the asbestos in her school, a problem that caused teacher and student walkouts and more closures at several buildings. An elite high school’s ceiling caved in with water in the middle of the day. Research showed worrisome levels of lead in 99 percent of the city’s schools. A former student of mine, now working as a teacher in a Philly high school, reported that a piece of the ceiling of her classroom fell into the students’ desks during lunch break. Had they been in the room, her students would have been seriously injured.

Just like in Lansford, school buildings in Philly are falling apart. And as is also the case in Lansford, Philly’s school district is financially distressed. The chief financial officer in Philadelphia’s school district reports that the district is certain to face deficits heading into 2024.

Building our schools back better represents a unifying and concrete battery of improvements that could undercut the acid leaching out from the right wing’s desperate and hateful efforts to foment bogus racialized and sexuality-themed controversies.

What’s the lesson here? In short, it’s that the same constructive politics that passed the Whole Home Repairs Act could work in public education. School buildings across the country need help, whether their districts are urban or rural or the voters in them are liberal or conservative. Building our schools back better represents a unifying and concrete battery of improvements that could undercut the acid leaching out from the right wing’s desperate and hateful efforts to foment bogus racialized and sexuality-themed controversies at the local, state, and federal levels.

School buildings sit at the nexus of every level of American government. We know that constructive politics can work at the local and state levels, as the political alignment behind the Whole Home Repairs Act makes plain. And at the national level, there are several encouraging trends that make the issue look even better.

- Staying within Pennsylvania for a moment, the Democratic Party’s full support for Democratic Senate candidate John Fetterman is encouraging. People might know Fetterman for his recent barrage of social-media taunts against his GOP opponent, the celebrity carpetbagger Mehmet Oz—but Fetterman is more than an overnight meme. His support in Pennsylvania runs very deep because he visits places like Carbon County, in the state’s coal belt, and takes them seriously. He has branded himself as a politician from the forgotten steel towns of Pennsylvania—and he goes to counties that vote conservative, bringing a progressive message that resonates statewide. National Democrats don’t need to clone Fetterman in other races, but they can readily adopt the upgrading of school infrastructure as a cause that has the same broad appeal that Fetterman has mustered behind his Senate run.

- Far from coincidentally, infrastructure has been a cornerstone of the national Democratic strategy thus far in Joe Biden’s presidency. From the bipartisan infrastructure bill to the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act, Democrats now have a solid footing and a proven legislative track record to back up their promises to improve our civic infrastructure.

Public school infrastructure is even better in this vein, as it is traditionally a Democratic issue and combines the all-important building trades and construction industry with public education. Also, when there’s funding for fixing school buildings, guess what: local property taxes go down because the district doesn’t have to raise rates to cover costs. That would go a long way toward fighting the right’s focus on curriculum by turning the typically Republican-branded local tax-revolt issue on its head. Indeed, we know this works in Pennsylvania: Democratic Gov. Tom Wolf trounced his budget-slashing, one-term Republican opponent, Tom Corbett, precisely because Corbett cut education funding. - As the urgency of fighting climate change and reducing carbon emissions has finally been translated into sweeping federal legislation, school building infrastructure is a great place to make gains. Old construction buildings generate a large amount of carbon; Generation180 estimates that school facilities emit about 72 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year—the equivalent of about 18 coal power plants or 8.6 million homes. Reducing emissions is a winning issue with young people, a key demographic for Democrats. Fixing up the schools to make them greener will help shore up those voting blocs.

- Indeed, certain sections of the Inflation Reduction Act allow for the provision of public money to direct private capital toward investment in green infrastructure, particularly in poor and disadvantaged communities. Section 138 of the IRA creates the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund, the country’s first green bank, with $27 billion at its disposal. Through syndicated loans put together by groups such as the nonprofit Inclusive Prosperity Group, school districts across the country could get low-cost loans for green construction projects backed by federal dollars through a partnership of state-level green banks. So there’s no need for fiscal traditionalists to worry about “paying for it.”

School buildings are a winning issue in the battle over public education—while the right foments regressive outbursts over CRT and gay-themed materials in school curricula, the forces of genuine progress can rightly say they’re committed to quality inclusive education—and safe, non-polluting schools to deliver it. This sort of appeal redirects conversation across all the ideological divides that now convulse education politics, and takes optimal advantage of significant financial policy now in place to back it up.

But given the prevailing terms of engagement in the school wars, we also must ensure that we double down on our efforts to protect and strengthen intersectional democracy. The only reason this right-wing reaction has galvanized at this moment is because of the progress we’ve seen in anti-racism in the wake of the uprisings over the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others. It’s a non-negotiable demand of true social-democratic politics to protect our people. But that means going on the offensive in addition to defending our imperiled multiracial democracy against the right-wing menace. So as the right seeks to tear down all sorts of protections and provisions for kids, why not build?

David I. Backer is an associate professor of education policy at West Chester University. His research and organizing focus on education, ideology, and finance. He writes a weekly newsletter on these themes called Schooling in Socialist America.