For Juneteenth to be a legible symbol of American freedom, in the grain of other patriotic national holidays, it needs to reference a redemptive narrative arc, leading from slavery to liberation to something akin to material racial equality. That’s a vision at odds with the actual history of emancipation in this country—and to complicate matters further, the dominant narrative of racial redemption now gaining traction in our national politics is distinctly ahistorical and non-empirical. The broad outlines of this new brand of race denialism are expressed in the central directive found in most versions of anti-critical race theory legislation. That language generally runs as follows: schools are forbidden from asserting that “slavery and racism are anything other than deviation from, betrayals of, or failures to live up to, the authentic founding principles of the United States, which include liberty and equality.”

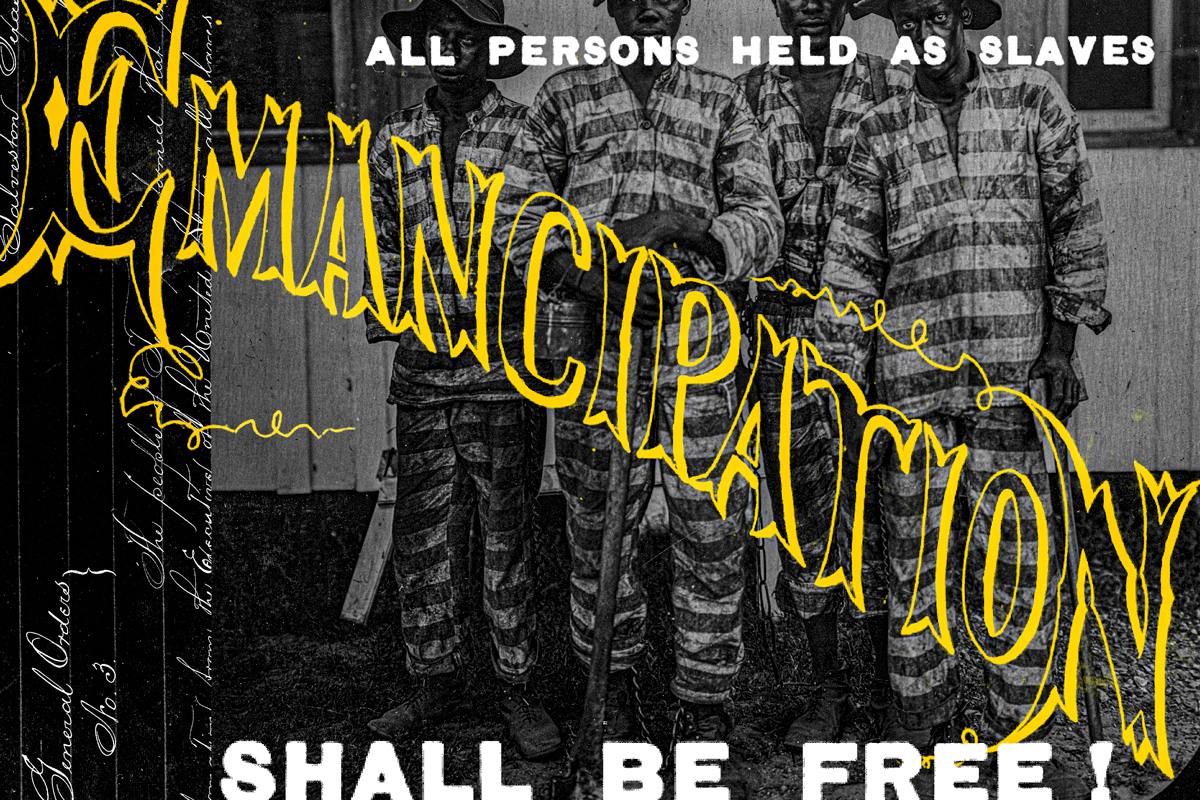

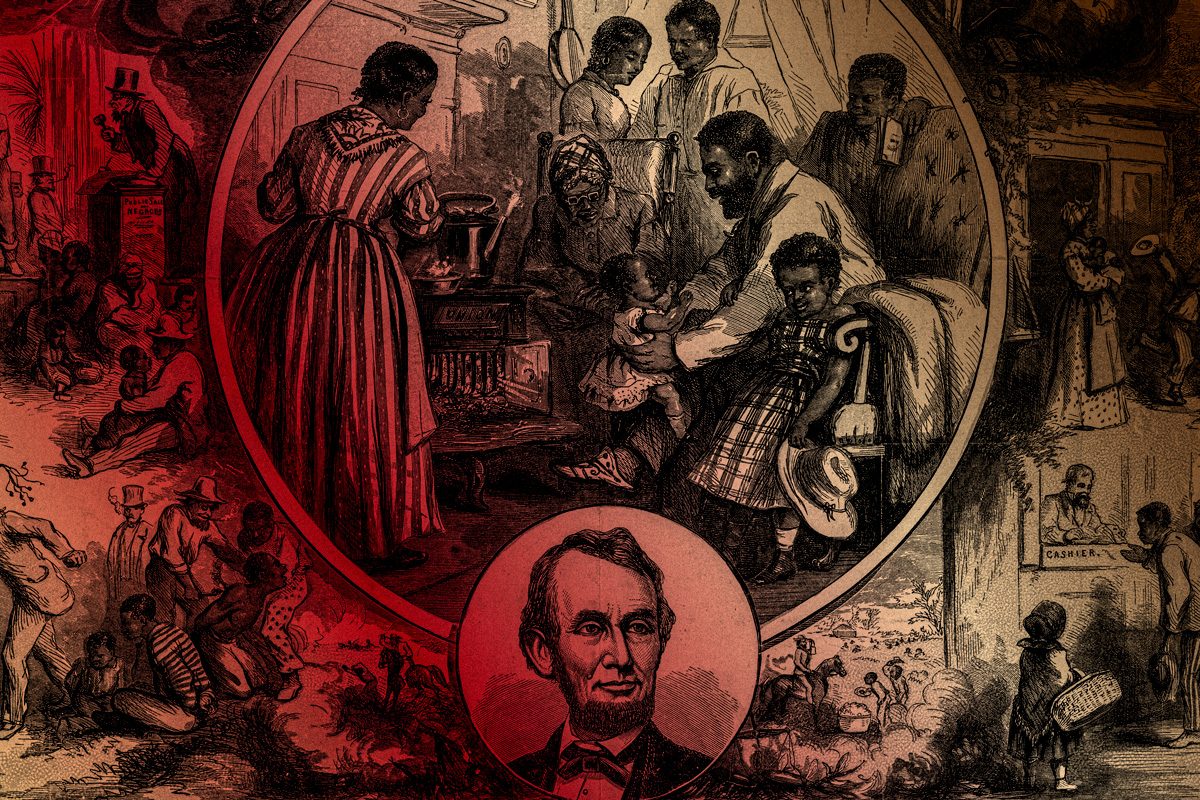

This narrative obviously comes up well short of the truth when it’s deployed to describe Juneteenth and its legacies. Juneteenth is the traditional African-American holiday celebrating General Order No. 3, the 1865 government directive that freed enslaved Blacks in Galveston, Texas. Under the terms of the traditional arc of national progress, the tacit logic of a whitewashed Juneteenth celebration goes broadly like this: slavery existed in the British colonies, America was founded, the country fought a war, Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves, Congress passed the 13th amendment. Slavery ended. America was redeemed.

The problem with this narrative is that it positions the rule of law as the event horizon of slavery. As the modern history of race inequality in this country dramatically shows, jurisprudence is a distinctly unreliable narrator of emancipation and American’s reconciliation with its “founding principles.” American society tends to depict jurisprudence as an arbiter of expansive democratic participation and social progress: an object study in America’s permanent standing as a “free country”—or a social order “born in perfection and aspiring in progress,” in the formulation of historian Richard Hofstadter. To believe that emancipation eradicated slavery in one fell swoop is to believe the boundaries of racialized enslavement end at the law’s renunciation of Africans’ bodily seizure and cross-generational reproduction as the “real estate” or chattel property of white people.

As a condition of actual social existence, however, being taken as a slave transcends the inability to possess your body or your labor. In his 1982 book Slavery and Social Death, sociologist Orlando Patterson outlines three basic constituents of the social extinction of a person. The first is brute domination: the element of power enforced through coercion—even when the enslaver is not physically present, the use of this force and power is omnipresent. The second is “natal alienation”—the system under which the enslaved person is barred from any rights to social order that inherently belong to other members of society (such as a last name, for example). The third is the repetitive dishonoring of enslaved people by behaviors that exemplify to them the daily social indicators of their complete powerlessness.

As this schema makes clear, the American enslavement of Africans was a multifaceted structure whose mechanics ultimately resided in a thorough system of violent and brutal social control. When slavery is understood in this light, it simply was not the case that the 13th Amendment expunged slavery from American social life; among other things, the 13th Amendment continued to explicitly permit enslavement as a punishment for a crime. Put another way: the 13th Amendment transferred the means of the production of slaves and ownership of their bodies from private white citizens to the state.

Carl Schurz, a German immigrant and a former general of the Union Army, traveled to the South to document conditions after the Civil War and said the following in a report to the Senate on the conditions of the South:

The emancipation of slaves is submitted to only in so far as chattel slavery in the old form could not be kept up; but, although the freedman is no longer considered the property of an individual master, he is considered the slave of society, and all independent State legislation will show a tendency to make him such.

As law professor Anthony Paul Farley wrote in his 2005 essay, “Perfecting Slavery,” this legacy continues unto this day: “we are animated by slavery. White-over-black is slavery and segregation and neosegregation and every situation in which the distribution of material or spiritual goods follows the colorline. The movement from slavery to segregation to neosegregation to whatever form of white-over-black it is that may come with post-modernity or after is not toward freedom. The movement from slavery to segregation to neosegregation is the movement of slavery perfecting itself.”

This insight forces us to reckon with a deeper, ugly truth—one that became unmistakable in the consolidation of Jim Crow rule after the failure of radical Reconstruction in America: For far too many Black Americans, emancipation did not represent slavery’s end but its perfection.

The 13th Amendment transferred the means of the production of slaves and ownership of their bodies from private white citizens to the state.

This dynamic, too, was implanted in the institution of chattel slavery in America from the outset. Since the first Africans arrived in Virginia in 1619, colonists used the rule of law to perfect slavery and proceeded to do so at the explicit sacrifice of their own customs, beliefs and theories of republican liberty. Under English common law, children inherited the status of their father. But that changed for Anglo-American colonists in 1662, after enslaved Blacks sued for their freedom based on confirmation of their baptism and the status of their fathers. Granting that precedent would undermine the need to have a monopoly on the means of producing slaves. So the white slave-owning class modified the law to mandate that children would inherit the status of the mother. In 1667, hereditary slavery was further codified with a law that said baptism did not exempt slaves from bondage—though slavery was not principally tied to Blackness until 1682, when a law stipulated that “negroes, moors, mollattoes and Indians” who were converted to the “Christian faith” are to be “taken as slaves.”

According to Farley, the perfection of slavery occurs when “the slave bows down before its master when it prays for legal relief, when it prays for equal rights, and while it cultivates the field of law hoping for an answer. The slave’s free choice, the slave’s leap of faith, can only be taken under conditions of legal equality. Only after emancipation and legal equality, only after rights, can the slave perfect itself as a slave.”

To ask for legal redress under such conditions, Farley argues, is to acquiesce to the status of enslavement: the inability to perform freedom without the permission of an enslaver or their rule of law is the perfection of slavery. In other words, to ask for freedom is to submit to the reality of enslavement. This is why requests for equality and freedom, as Farley notes, will fail “whether the request is granted or denied” because the request is produced through an injury. “The initial injury is the marking of bodies for less—less respect, less land, less freedom, less education, less,” Farley writes.

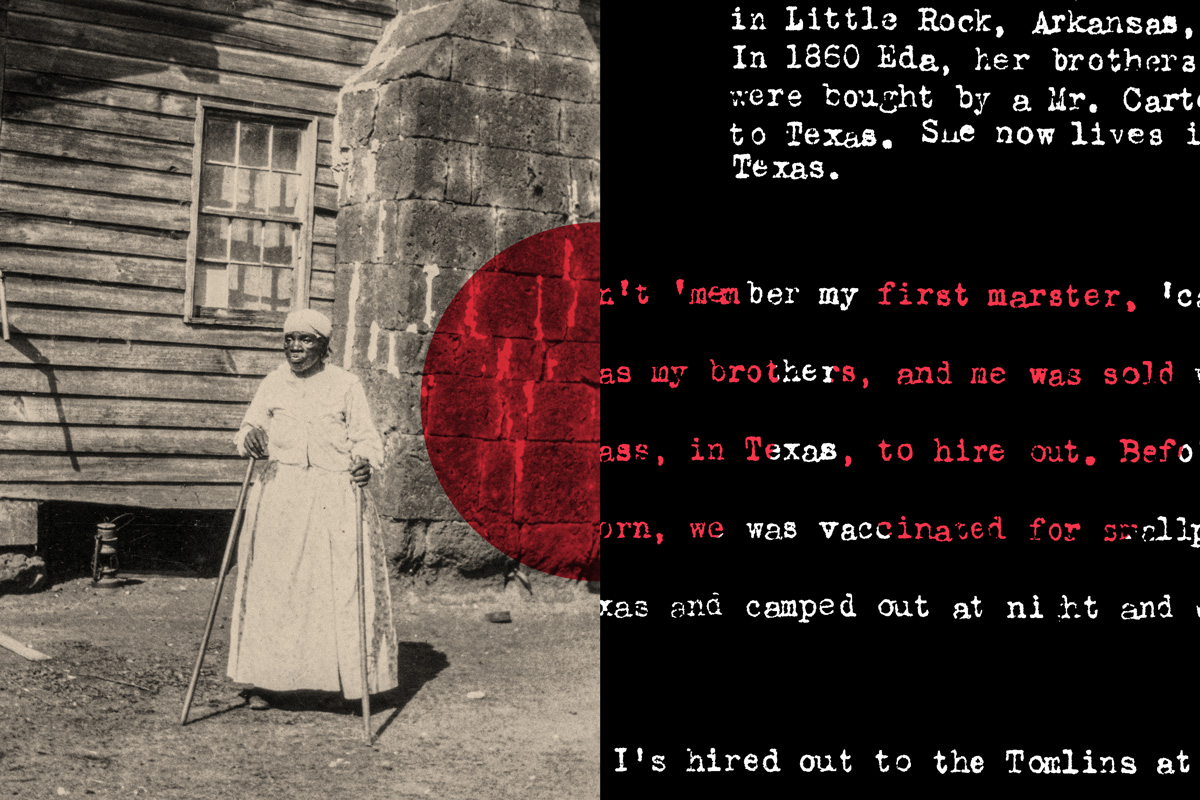

The injury taints the fulfillment of a request for equal rights because it redefines rights as gifts bestowed by powerful oppressors, and recasts progress as a further rationalization of submission. Understood in this light, white freedom and Black emancipation were two different paradigms—even though they operated in dialectical tandem. White freedom was the power to define, embody and disseminate freedom. “The Master he says we are all free, but it don’t mean we is white,” said George G. King, who was enslaved in South Carolina and gave a firsthand account of emancipation to the Federal Writer’s Project in 1937. At the age of 83, King testified to the stark reality of “freedom” for freed slaves: “It don’t mean we is equal. Just equal for to work and earn our own living and not depend on [the white man] for no more meats and clothes.”

One of the chief evils of slavery was this very distorting effect. It simultaneously imparted the enslaved with the desire of freedom while also forcing the stark realization that if the enslaved attempted to be anything other than enslaved, death is the consequence.

After northern troops moved throughout the South to notify the conquered Confederate population of emancipation, some enslaved Blacks waited for their enslavers to confirm their freedom. One formerly enslaved Alabamian said that it “didn’t do to say you was free. When de war was over if a [Black person] say he was free, dey shot him down. I didn’t say anythin,’ but one day I run away.”

A formerly enslaved North Carolinian testified to what happened to freed Blacks after Union troops announced that emancipation had happened. “They tol’ us we were free,” but the master “would get cruel to the slaves if they acted like they were free.”

And this brings us back around to the commemoration of Juneteenth. On July 13th 1865, a little over a month after General Order No. 3 was executed in Galveston, Texas, The Galveston Daily News published a letter written by a white enslaver recounting the decidedly equivocal manner in which enslaved Blacks learned of their freedom:

The owner’s duty is to tell the negro he is free, and not only that, but he must explain to him every thing about it, and what freedom means. All the negroes who have been under my charge during the war have been appraised of the sudden change in their condition, and judging from their work and behavior up to the present, you would not know they were aught but slaves.

[redacted] told his negroes and explained to them their condition, they are all at work. I told ours and I can see no difference. I tried to explain to them their present condition, that freedom meant with them the necessity of working harder than they had ever done; that it made no difference where or with whom they went, they would have to work and not only for themselves, but also for their government; that they, like myself would have to pay taxes.

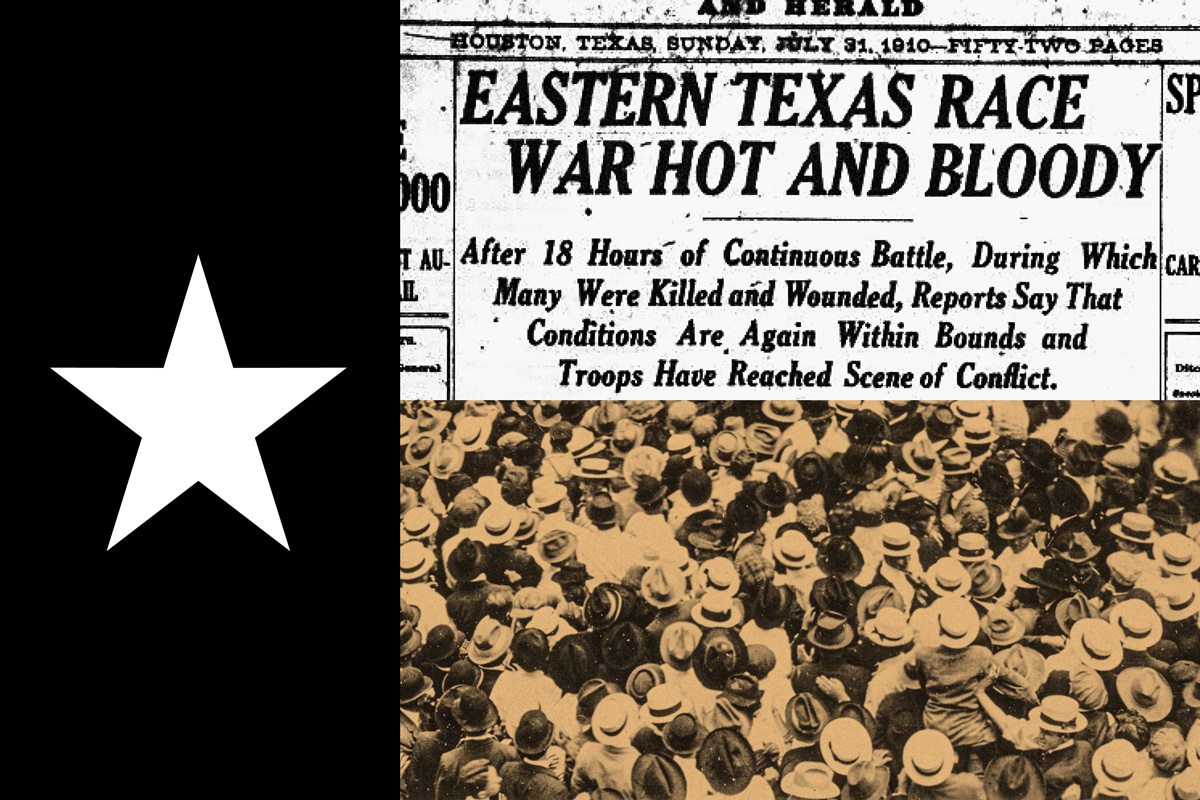

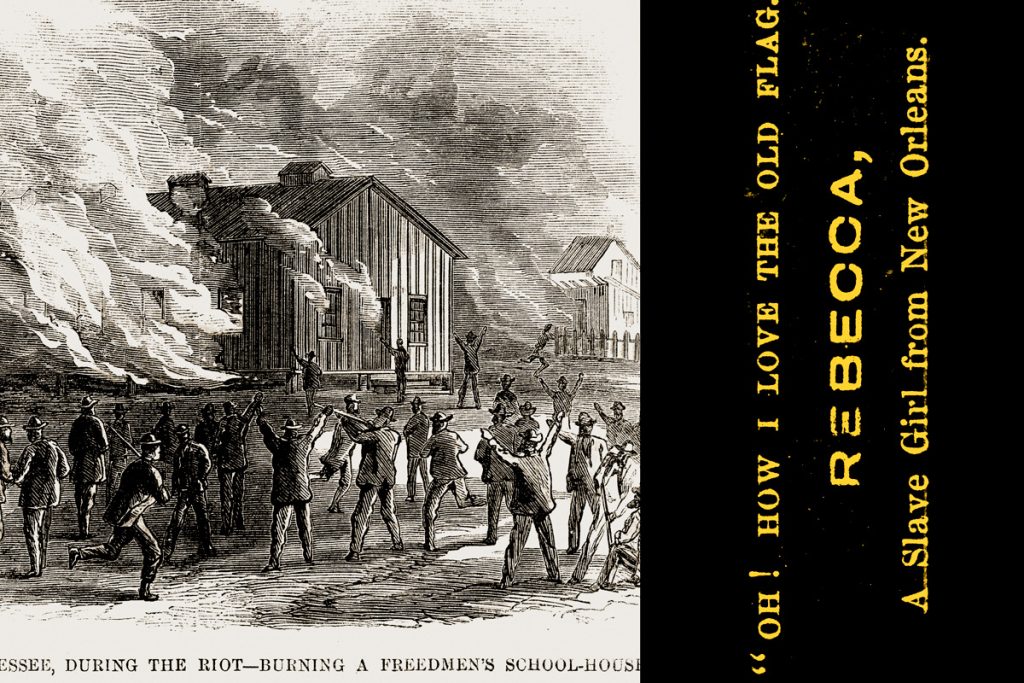

Black emancipation was different than enslavement, to be sure. But as such testimonials make clear, it remained inseparable from the experience of enslavement because the bond of slavery and Blackness was not solely a matter of legislation. If it were, slavery’s status as an illegal institution would have eliminated anti-Black racism completely, as the present wave of CRT bans would have us believe. In truth, however, emancipation did not disrupt the orientation of Blackness as socially cognate with enslavement—nor did it remove white supremacists’ libidinal urges to commit acts of violence on Black people in order to sustain the white-over-black paradigm that defined the American experience of race.

To further bolster the white-over-Black paradigm and to perfect slavery, southern legislators exploited the 13th Amendment’s exception for slavery as a crime to transfer it into still another expression of slavery as social death. They swiftly moved to make Black synonymous with criminal. Emancipation presented planters with a question: how to reestablish slavery without the former institutional bulwarks of enslavement? The answer was to ratify a whole suite of laws to coerce labor through sharecropping and vagrancy. These were the “needed laws” planters advocated for in newspapers and farm journals as a solution the “altered system of labor.”

In very short order, the “altered system of labor” was remade in the image of antebellum enslavement. After emancipation, white planters exhorted freed Blacks to return to their plantations and work the land for “fair wages” as stipulated within labor contracts. The ultimate coercive force behind these contracts was the postbellum South’s new battery of vagrancy laws. These measures explicitly marshaled the threat of state violence to force Blacks into ruinous contracts aimed at producing their long-term disfranchisement from political-economic citizenship as white America defined it.

For far too many Black Americans, emancipation did not represent slavery’s end but its perfection.

All the former Confederate states except Tennessee and Arkansas passed new vagrancy laws in 1865 or 1866. Under their provisions, Blacks arrested for vagrancy would face exorbitant fines—and if the fine could not be paid, the “vagrant” would be auctioned off to a planter, who would pay the bound-over worker’s wages to the state. White landlords used this system to keep Black farmers in debt and tied to the land. Whites loaned Black farmers capital in order to harvest the land, but again at unsustainably high interest rates. This brand of economic predation, combined with the adverse impacts of unpredictable harvests and racist landlords, created a cycle that folded Black farmers back into slavery.

Frederick Douglass, among other Black leaders of the age, called out the enduring fact of enslavedness after emancipation. In 1888, Douglass indeed announced that the freedman

is the victim of a cunningly devised swindle, one which paralyzes his energies, suppresses his ambition, and blasts all his hopes; and though he is nominally free he is actually a slave. I here and now denounce his so-called emancipation as a stupendous fraud.

…

Take his relation to the national government and we shall find him a deserted, a defrauded, a swindled, and an outcast man —in law free, in fact a slave; in law a citizen, in fact an alien; in law a voter, in fact, a disfranchised man. In law, his color is no crime; in fact, his color exposes him to be treated as a criminal.

Following on this foundational deployment of the rule of law to continue tethering slavery to Blackness, white southerners built up an additional body of legislation to distinguish Black vagrants and white vagrants. Vagrancy laws existed before the full announcement of emancipation in 1865—but when enslaved Blacks were freed, there were no distinctions between a white vagrant and a Black vagrant. In 1857, to take one example, Mississippi defined a vagrant as “all able bodied persons who live without employment, or labor, and have no visible means of support or maintenance,” and assigned the status of vagrancy to a generic body of reckless economic behavior—from family abandonment to compulsive gambling.

But in 1865, Mississippi amended the law to define vagrant in racialized terms. The impact of this racial reclassification stretched across decades: In September 1901, a report in the Atlanta Journal and Constitution matter-of-factly announced that city and county officers in Jackson, Mississippi drove “vagrants and idlers” into cotton fields, where the farmers are “crying for labor to pick the season’s crop”—leaving white readers in no doubt about the underlying racial dynamics of this seasonal mobilization of workers reduced to debt peonage under vagrancy law. A 1904 dispatch from the Chattanooga News said the quiet part out loud: planters in Covington, Tennessee had “planned to raise larger crops” but “were handicapped” because of the “labor conditions,” so authorities commenced a “wholesale arrests of idle negroes” because of the “scarcity of labor in the cotton fields.”

In America, racial progress spins backward. The status-based progress symbolized by emancipation directly sparked the adoption of the postbellum South’s notorious Black Codes, laws designed to specifically keep freed Blacks confined within a slave caste. In the same fashion, the progress partially realized under the 14th Amendment—the promise of equal protection under the law—segued into the apartheid social order of Jim Crow. And down through today, the progress gained under the formal repudiation of Jim Crow is now succumbing to a fresh surge of reaction and retrenchment, with the rollback of voting rights for Black communities, the normalization of lethal police violence on Black Americans, and the distinctly predatory regime of social death that now goes by the name of mass incarceration. This is all to say nothing, of course, of far more routine and racialized savage inequalities, from chronic income and wealth disparities based on racial subordination to racially segmented and diminishing access to housing, health care, education, and other basic forms of social provision. The story of “up from slavery” is the story of freedom kept down in its totality—and this is the lesson of Juneteenth and its legacies that many Americans are now determined to ensure shall never again be taught in our schools.

Anthony Conwright is a writer and AAPF fellow living in New York City. Follow him on Twitter @aeconwright.