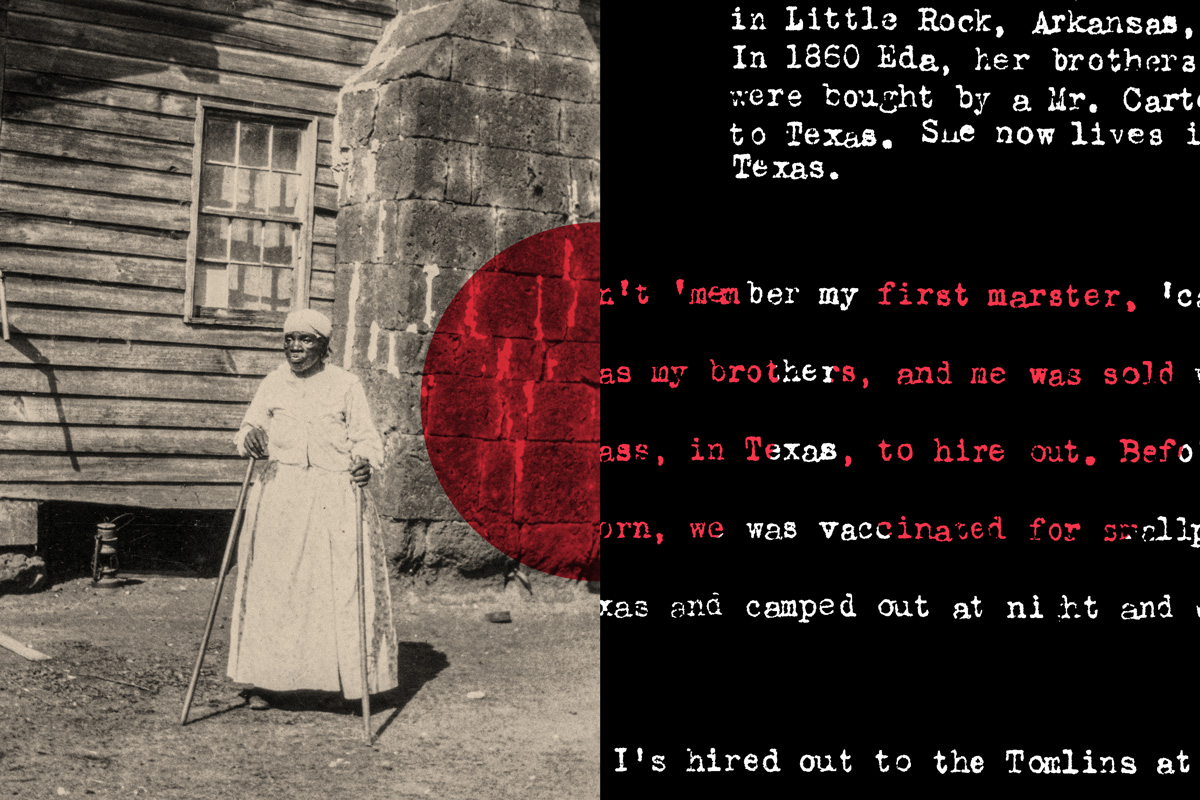

When the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) sent its mostly white interviewers out across Texas between 1936-1938, they were charged with collecting the stories of formerly enslaved Black people. Of the Black women interviewed, some had been born enslaved in Texas, some had been moved there by white slave masters as the Civil War reached a fever pitch, and even more had set out to live with children or grandchildren in the decades following emancipation.

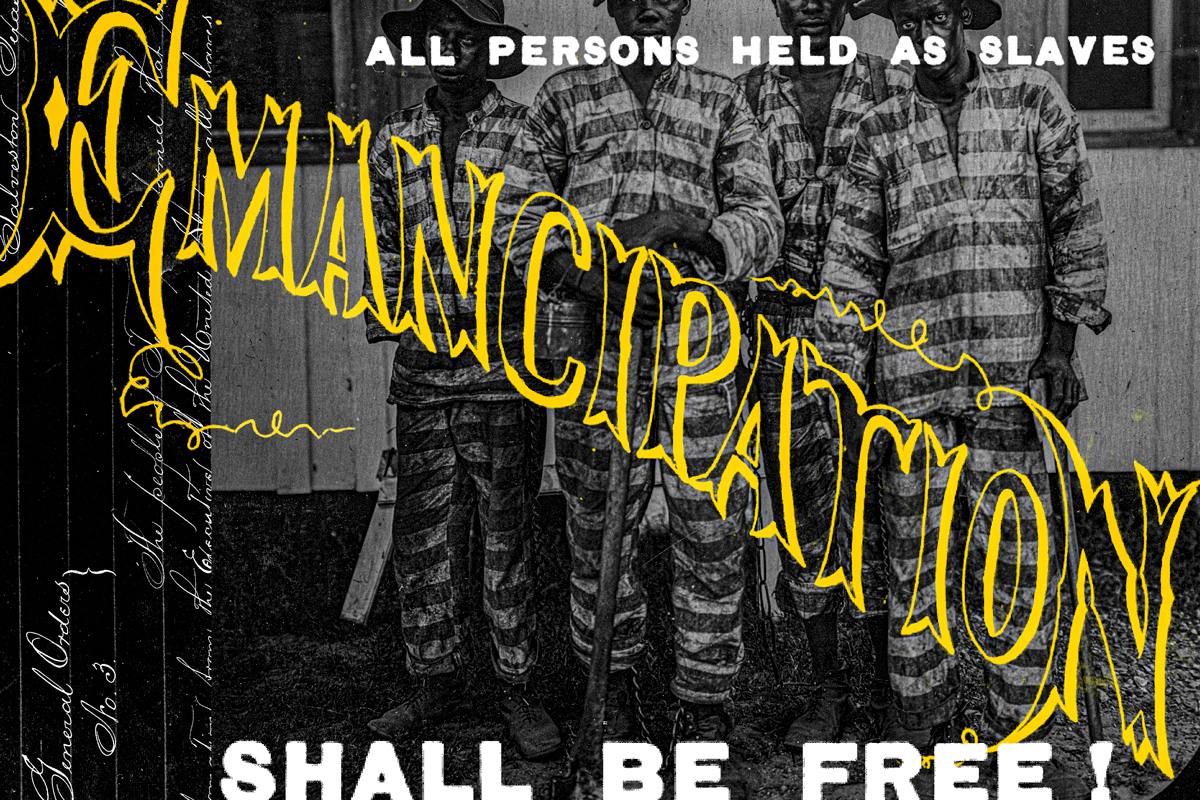

What’s striking about those interviews—collected 71 years after the first Juneteenth in 1865, when union troops marched into Galveston, Texas to enforce the emancipation proclamation handed down nearly two years prior—is that they often found Black, formerly enslaved women in circumstances both markedly different and largely unchanged from those they lived through during enslavement. As we conclude another Juneteenth celebration, their voices rise above the myth-making and corporate marketing marshaled behind the second federal commemoration of the holiday, and ask us to consider what the promise of liberation means today for Black women, girls, and femmes.

Unlike their Black male peers, freed Black women found that the right to vote, not to mention legislative representation, didn’t emerge as even a distant possibility until the winter of their lives.

The formerly enslaved women interviewed as a part of the FWP were mostly in their 80s and 90s. Their recollections about the time of enslavement varied, their experiences of direct cruelty at the hands of their white slave masters differed, and yet their stories were achingly similar. Rosanna Frazier of Beaumont, Texas remembered that her mother was from a free country, captured and sold into the brutality of chattel slavery. Martha Patton, who was 91 at the time she was interviewed in Goliad, Texas, had outlived most of her children, “I has ten chillen; seven of them are living, I have fifteen or nineteen grandchillen,” she told the WPA archivists. “But I don’t know where dey all are or what dey are doing.” She wasn’t alone. Aunt Eda Rains, who was sold at the age of seven to a white woman slave owner, outlived most of her ten children.

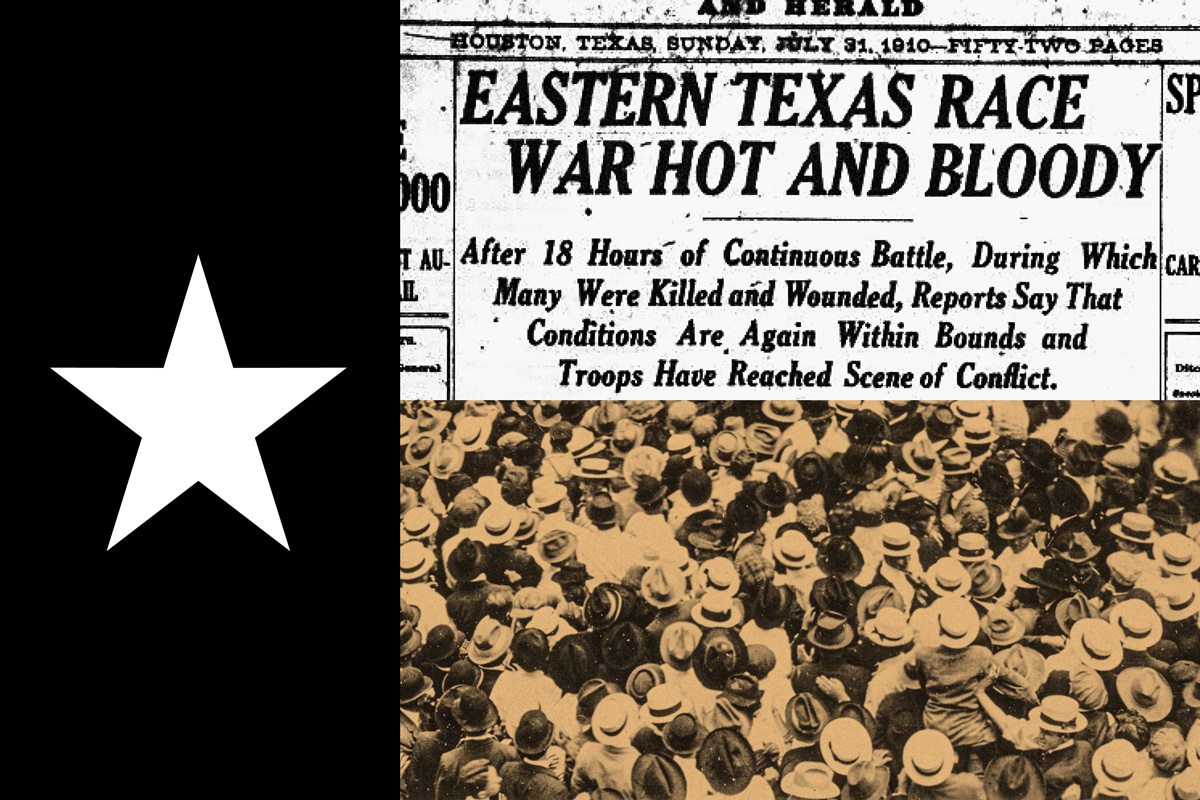

Many more of the women interviewed for the project had also lost children and grandchildren, presumably to limited or nonexistent access to health care, lynchings and state violence, or other systemic causes. Most had exited slavery only to find themselves immediately conscripted (no matter their age) into sharecropping or other back-breaking work. And unlike their Black male peers, they found that the right to vote, not to mention legislative representation, didn’t emerge as even a distant possibility until the winter of their lives, when it was rapidly curtailed by poll taxes and literacy tests.

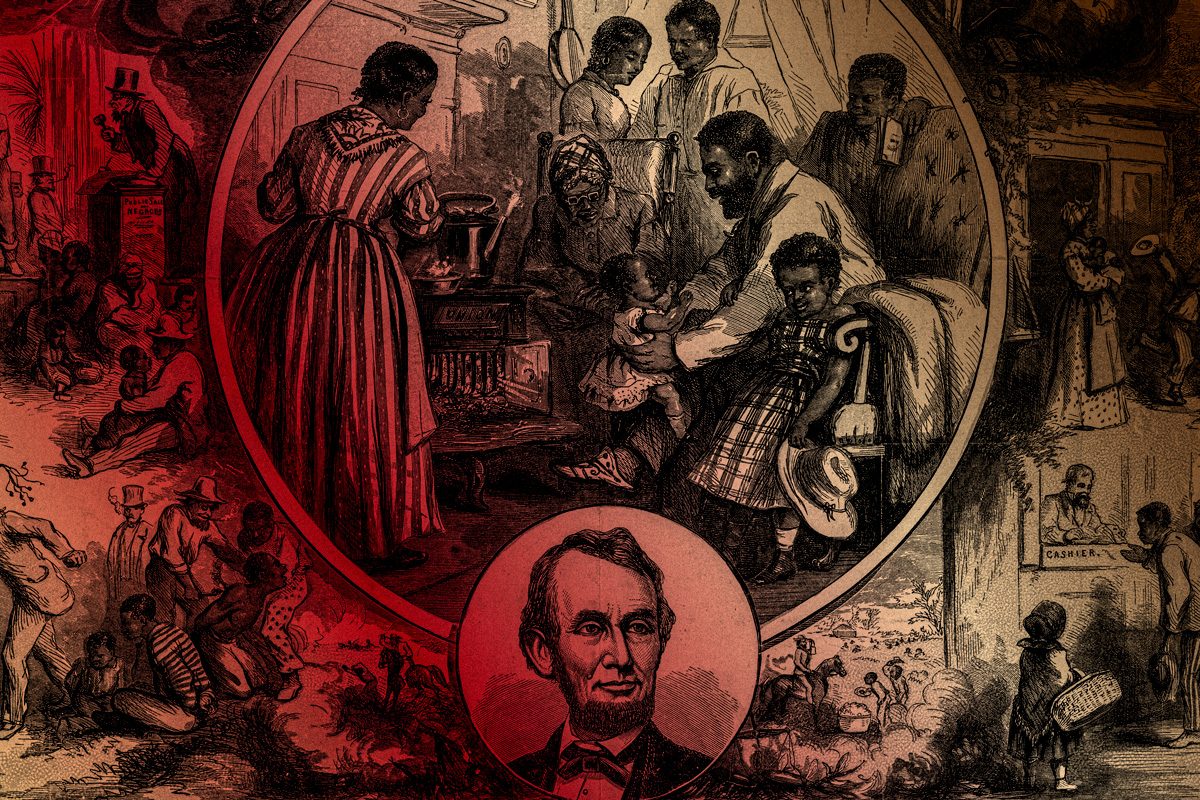

Living through enslavement, Reconstruction, the subsequent white backlash, and the transition into the twentieth century, these women knew first-hand that while the promises of efforts like Reconstruction and suffrage were great, the actual options available for Black women were limited. The decades after emancipation were marked by racial pogroms, the rise of white terrorist groups like the Ku Klux Klan, and local and federal policies designed to ensure white dominance and Black subjugation—in particular the sublimation of Black women’s autonomy and freedom. Ordinances, federal law, and de facto discriminatory policies throughout their lives would continue to mark the intersecting status of Black and woman as a class of people both targeted and invisibilized.

At its core, Juneteenth is a promise. A nation state, no matter how powerful, cannot confer freedom to human beings. However, the work of federalized emancipation was a formal acknowledgement—a “promissory note” in the words of Martin Luther King Jr.—that should have bound the American nation to ensure its Black citizens full access to the services, protections, and liberties they deserved by simple virtue of their humanity. As we continue to take stock of the country’s complete failure to honor this promise, as we excavate the culpability of the politicians and power brokers who originally tendered it, we also know their abandonment of Reconstruction was deeply rooted in their limited view of who belonged at the decision-making tables when the terms of emancipation were worked out. It was Black women’s active exclusion from the work of dismantling the centuries of legislation enshrined on their own bodies that ultimately made the promise of that first Juneteenth hollow. The arc of American history would have followed a far more dramatic—and far more equitable—path if the foundational vision of Reconstruction had taken shape through the lens of Black feminism.

When we think about Black feminism in America, one of the central touchstones is the incredible work of The Combahee River Collective. Their landmark 1977 statement was a pivotal work in Black feminist theory, but one of its most powerful sentences it also one of the simplest. Its writers, a collection of Black queer femmes and women, magnificently announced, “Above all else, our politics initially sprang from the shared belief that Black women are inherently valuable, that our liberation is a necessity not as an adjunct to somebody else’s but because of our need as human persons for autonomy.”

Today, this self-same right to human autonomy remains under direct threat by the forces of white nationalist and patriarchal reaction. As was true for the Black female survivors of enslavement in 1936, and for their spiritual heirs and descendants among the Black feminist activists in the late 1970s, the simple human autonomy of Black women, girls, and femmes remains under concerted siege. This hostile political culture, determined to deny the basic precepts of intersectional justice, exists regardless of which political party holds power and across virtually every sphere of American life. In healthcare, maternal mortality for Black women remains alarmingly high. Even as scientific innovation makes maternal death statistically less likely worldwide, Black birthing people in America are three times more likely to die of complications related to childbirth than their white counterparts. Because of this socially constructed disparity, access to abortion services is a critical element in ensuring the right to thrive for Black women—a right that is currently threatened to be fully repealed by both the federal judiciary and state legislatures.

It was Black women’s active exclusion from the work of dismantling the centuries of legislation enshrined on their own bodies that ultimately made the promise of that first Juneteenth hollow.

In the workplace, Black women remain at the bottom of the income ladder. According to the Center for American Progress, “Over the course of a 40-year career, Black women lose an estimated $964,400 to the wage gap.” This inability to amass wealth through income cascades from Black women throughout Black families, and ensures that the descendants of the enslaved and sharecroppers remain in a protracted state of financial instability. In all levels of government, Black women remain woefully underrepresented. In the 157 years since emancipation, there has never been a Black woman governor of any American state and only two Black women have ever served as U.S. Senators. In 2022, Ketanji Brown Jackson became the first ever Black woman confirmed to the U.S. Supreme Court—in spite of a right-wing campaign to denigrate and derail her nomination, steeped in the dog whistles of misogynoir.

If the promise of Juneteenth is, in part, the right to fully govern oneself, Black women remain confined to forms of official representation that are rigidly understood as either Black or woman, but very rarely both. These continuities—or rather fundamental inconsistencies—in Black women’s struggle to assert and defend their simple right to autonomy and self-governance persist because the foundations of our political, medical, and economic systems are built with the same misogyny, heteropatriarchy, and racism that prompted The Combahee River Collective to take up their work nearly 50 years ago.

A Juneteenth that lives up to its promise for the Black women, girls, and femmes of America can begin to rectify at least some of these foundational harms by fully documenting and addressing their particular vulnerability to state violence. A Juneteenth that makes good on the full promise of emancipation across genders, must directly disown the slanderous campaign to suppress and censor critical race theory, intersectionality, and critical legal study. A Juneteenth worthy of its name must face the ongoing social violence wrought by the child welfare system and its disproportionate impact on Black women and families—and ensure baseline social protections can at long last start to reverse that damage. And a Juneteenth that answers the call of Black feminists and theorists from enslavement to the present day must attend to the intersectional failures of the past by centering and elevating the voices, stories, and decision-making of Black women, girls, and femmes in the struggle to make good on the promise of true emancipation and lasting equality for Black America.

Nicole Young is a writer whose work has appeared in Elle, Vox, ZORA, and Bitch magazines. She loves to talk about race, Black womanhood, politics, and children’s literature. She is currently living in Philadelphia.