Editor’s note: In January 2022, AAPF Executive Director and Co-founder Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw received the American Association of Law Schools’ Triennial Award for Lifetime Service to Legal Education and the Legal Profession. To mark the occasion, she delivered a speech laying out the dynamics of white backlash in America’s struggle for democracy—and the legal profession’s own historical role in shoring up the foundations of racial retrenchment. We are pleased to publish this edited excerpt from Dr. Crenshaw’s remarks at the Forum; you can read the full text, also edited for print publication, at the UCLA Law Review.

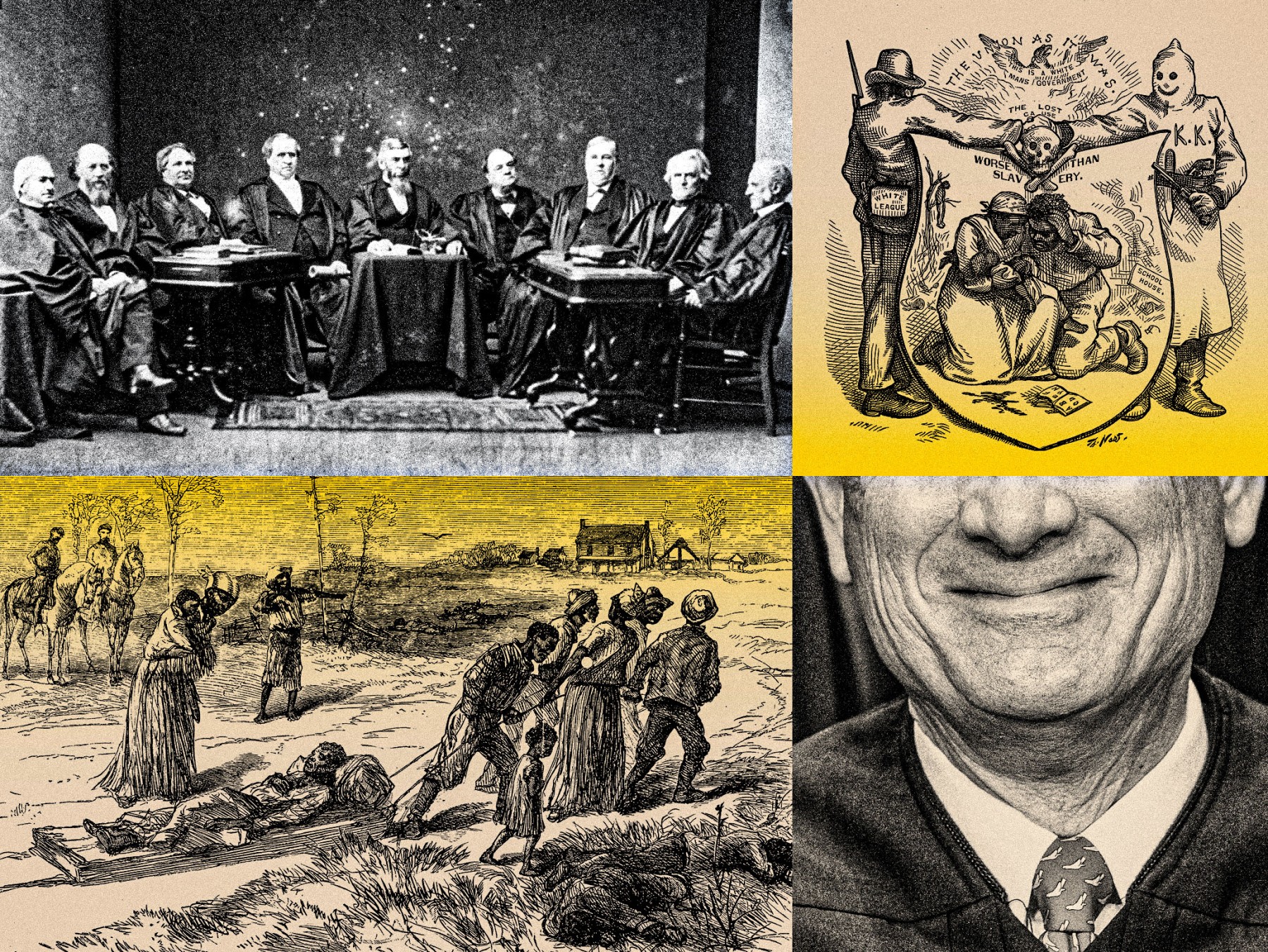

Across much of my career, I’ve wrestled with the deep foundations of racial retrenchment in American society—the process by which incremental steps toward collective justice get broken down and reversed and reframed as discrimination against white people. In this way, Herculean efforts to create a functioning multiracial democracy get recast as sources of grievance for those who justify aggressive efforts to restore the status quo. The lethal ends that retrenchment politics have served were historically aided by law, as the overthrow of Reconstruction illustrates.

This tragic dynamic was in full force when Reconstruction’s efforts to limit the dehumanizing dimensions of white supremacy were destroyed by a massive and coordinated campaign of racial terror, legislative disfranchisement and judicial neglect, all abetted by the acquiescence of northern elites. One might have hoped that these lessons about the fragile foundations of our democracy would have been absorbed and metabolized by our body politic over the past century and a half. We could then face the resurgence of retrenchment politics armed with the simple, historically incontrovertible truth that there is no daylight between the fight against racism and the fight for our democracy.

With this understanding as Ground Zero for the struggle to achieve and sustain our multiracial democracy, one would have further hoped that the racial reckoning of 2020—touched off by the largest protests in our history—could have opened pathways toward more, not less, critical thinking about racial power—its legal and structural dimensions, and its constant threat to our democracy. One could then have reason to believe that the massive backlash to the reckoning—the efforts to suppress nonwhite voting, the insurrectionist attempt to overthrow our government on January 6, 2021, and the continued weaponization of nativist and racist appeals to a politics of militant white grievance—would have inspired efforts to shore up democratic ideals. One might also have hoped that the intellectual and political work of critical race theory, which has rigorously engaged with and helped to explain all these dynamics, would have played a leading role in this crucial work of democratic reclamation.

Instead, the opposite has happened. We are now, unfortunately, facing a moment where retrenchment politics are rapidly accelerating, once again threatening the existential future of our democracy. Critical race theory and intersectionality have not only been labeled as “divisive,” “dangerous,” and “un-American”; they have also been appropriated as a container to denounce the wider project of antiracism and social justice writ large.

Across the country, a moral panic over what has been labeled CRT has led to the firing of accomplished teachers like Matthew Hawn in Tennessee, the canceling of Black and Latinx studies courses in Texas, and the creation of bounties on teachers in New Hampshire and in North Dakota. Politicians have sought to censor any study of the way that the American legal system sometimes facilitates and reinforces racial inequality. That legislators can appropriate law to banish critiques of law should rattle every last one of us. Changing the rules about what racial histories can be taught, and what experiences can be acknowledged is not a healthy feature of a robust democracy. It is, in fact, its opposite: a democracy in peril, in danger of succumbing to the rising tide of authoritarianism.

One would have hoped that the racial reckoning of 2020—touched off by the largest protests in our history—could have opened pathways toward more, not less, critical thinking about racial power.

This censoring of knowledge—along with measures suppressing voting and criminalizing protest—represents something much more dangerous than a tactical maneuver to prevail in the next political season. This is a strategy to seize power for a century, and beyond. And mainstream media contributes to the moral panic by being slow to expose the source and motivation behind the effort, resorting to a both-sides approach that fuels the stealth disinformation campaign to demonize CRT.

That civil society seems to be lethargic in the face of what has been mislabeled as a “cultural war” only adds to the urgent need for educators to confront the crisis facing our democracy. Legal educators—those who believe we will find refuge in the law—soon will be faced with crucial challenges concerning how to teach, think, and act in the face of this profound breach of our professed norms.

This will not be the first time that legal education must navigate a world in which law has been used to enforce and normalize racially repressive conditions. Legal education was far from the forefront of efforts to problematize the legalized theft of land, labor, and freedom that underwrote our nation’s creation and rapid expansion. Nor did it lead the way in rethinking and dismantling the institutionalized dimensions of white supremacy that survived the mid-twentieth century repudiation of segregation. Before Derrick Bell’s Race, Racism & American Law casebook, there was little academic analysis of how the formally neutral doctrines, values, and practices that undermined the post-Reconstruction amendments to the U.S. Constitution continued to ratify racist social arrangements that were directly traceable to Reconstruction’s overthrow. Elite institutions that prided themselves on educating lawyers to serve modern society were woefully ill equipped to nurture the legal talent needed to disentangle white supremacist values from legal doctrine and practices. Consequently, many institutions, and the lawyers and scholars they incubated, were left on the sidelines of the most significant matters of the day.

In fact, the legal revolution that Brown v. Board represented emerged from the segregated classrooms and libraries outside of the rarified center of legal education. Decades later, our post-civil rights generation of matriculating law students encountered a studied agnosticism toward the legally facilitated dimensions of racial subordination. The uninterrogated past remains embedded in the courses that were taught, the cases that we read, the legal problems that were prioritized, the measurements of legal talent that were embraced, and the interests that were privileged.

In addition to acknowledging their academic agnosticism toward white supremacy, we must recognize that our legal institutions actively facilitated separate-but-equal segregation in the years preceding the Second Reconstruction. In the era of Jim Crow, both the American Bar Association and the AALS approved the country’s first “Jim Crow law school” at Lincoln University in St. Louis in December of 1941. Rather than allow Lloyd Gaines to desegregate the University of Missouri School of Law, the Missouri state legislature created an entirely new segregated law school for Black students in St. Louis. The University of Texas likewise sought to stave off the integration of its law school with a hastily built school for Heman Marion Sweatt, another Black first-year law student whom the apartheid South sought to marginalize. Ultimately, the U.S. Supreme Court’s overdue repudiation of such schemes provided a doctrinal building block for segregation’s formal demise in Brown v. Board of Education.

For generations, mainstream legal education would sustain a matter-of-uncontestable-fact attitude toward law and racial power, detached from the hard realities faced by the least of us. Convinced that neither the future of American democracy nor the stability of the Republic required otherwise, our leading law schools ensured that the legal structure of racial subordination remained a topic far removed from the center of legal theory and practice. This apparent consensus reflected little awareness of how faith in our democracy rested on racial quicksand. Yet the January 6 assault on the U.S. Capitol tells us otherwise. Among the images of rioters who stormed the Capitol to “take our country back” was the Confederate battle flag, long a symbol of righteous rebellion for those who chose to break with the nation rather than share it one day with those they had enslaved. These sentiments have not died but have evolved. It is not an accident that the lies about the 2020 election being stolen are centered in places like Detroit, Milwaukee, Atlanta, Phoenix, and others where the choices of nonwhite voters handed the White House to President Biden. Yet the current connections between our anti-democratic and racist history are readily obscured by a profound ignorance about the violent origins of our contemporary political order. Our newly elected president said at the time of the insurrection that this is not who we are. But even a cursory history of Redemption reveals that this is exactly who we have been. For those who wonder whether our democracy can go off the rails, if “it” can happen here, we need only heed our past to know that “it” already has. To understand how explicitly anti-democratic desires can be framed as defending freedom, we have to grapple with discomforting histories and their contemporary reflections, particularly those that have been obscured by myths and rehearsed in our academic institutions.

We can only hope that recovered memories of the relationship between authoritarian tyranny and white supremacy make it abundantly clear that attacks on democracy and attacks on antiracism are fruits of the same poisonous tree.

We can only hope that the events unfolding since January 6 are now game changers, that recovered memories of the relationship between authoritarian tyranny and white supremacy make it abundantly clear that attacks on democracy and attacks on antiracism are fruits of the same poisonous tree. We’ve seen this movie before, and we can see where this is going. The time to write a different ending is now.

One of the promises that my parent’s generation—the race men and women of the 20th century—bequeathed to us was the commitment to do everything possible to hand us the baton with the lead. This basic commitment is the least that antiracists and true democrats across the political spectrum should be keen to embrace now. Future generations deserve a rich inheritance, enhanced by the lessons, the struggles, and the victories of those who have come before. Yet, with the resurgence of know-nothing laws, policies, and demands, we are witnessing an erosion of our hard-won literacy. Without the ability to see and convey the threats to our multiracial democracy, we are left woefully underprepared to address them. These are dangerous times—for justice, for democracy, and for law itself. As James Baldwin once noted, “ignorance, allied with power, is the most ferocious enemy justice can have.”

The challenge we face now as educators is to refuse to accept these conditions as the new normal and to be as ferocious in the fight against ignorance as others are in the fight to impose it. We need to shore up our commitments to academic freedom and bravely confront the vestiges of our profession’s past collaboration with white supremacist values and practices. It will take the support of colleagues throughout the profession to reverse the current descent into a new McCarthyism. The possibility of syllabi, research dollars, and permissible perspectives being dictated by politicians in state capitals across the country is no longer a distant possibility. This is not a drill.

It is folly to assume that by waiting for the storm to pass cooler heads will prevail and our institutions will hold. When we have lost our way in the past, it was not simply because the forces of repression and fear were too overwhelming to deter, but because the silence and complacency of too many allowed an autocratic faction to alter the trajectory of our democracy. Toni Morrison speaks of how the tragedies that have marked human history have sometimes issued from the unholy marriage of aggression and silence. She describes the process through which failures to object to positions that were once unthinkable evolve into conditions that are naturalized, accepted, and advanced. Is this far afield from what is happening in our democracy as we speak? As we ponder whether the worst-case scenarios might happen here, Morrison urges us to consider how our capacity to see “it” may be lost in the numbing failure to resist the steps along the way.

I sincerely want to believe that the moral arc of the universe bends toward justice, but I believe that nothing is inevitable. Hope, for me, rests on reading our current situation with full awareness of our past and acting on what we see. We must resist fiercely every war waged against teaching discomforting truths about racism in America. And we must meaningfully confront the complex role that the legal profession has played in the struggle for true and abiding racial justice.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw is the co-founder and executive director of the African American Policy Forum.