Nobody in the GOP wanted to face the truth that was glaring at them. On August 3, the day after a special election was held in red Kansas, a surprising outcome had emerged. Presented with a ballot measure that would modify the state Constitution to remove existing protections for abortion rights, voters resoundingly rejected the measure. When the results were finally tabulated the percentages should have been a sign of things to come. 59 percent of Kansans had voted “no” and chosen to keep the protections as they were. The extreme no-exception measures that many Republican Kansas lawmakers had wanted to pass since the overturning of Roe v. Wade by the U.S. Supreme Court would not proceed.

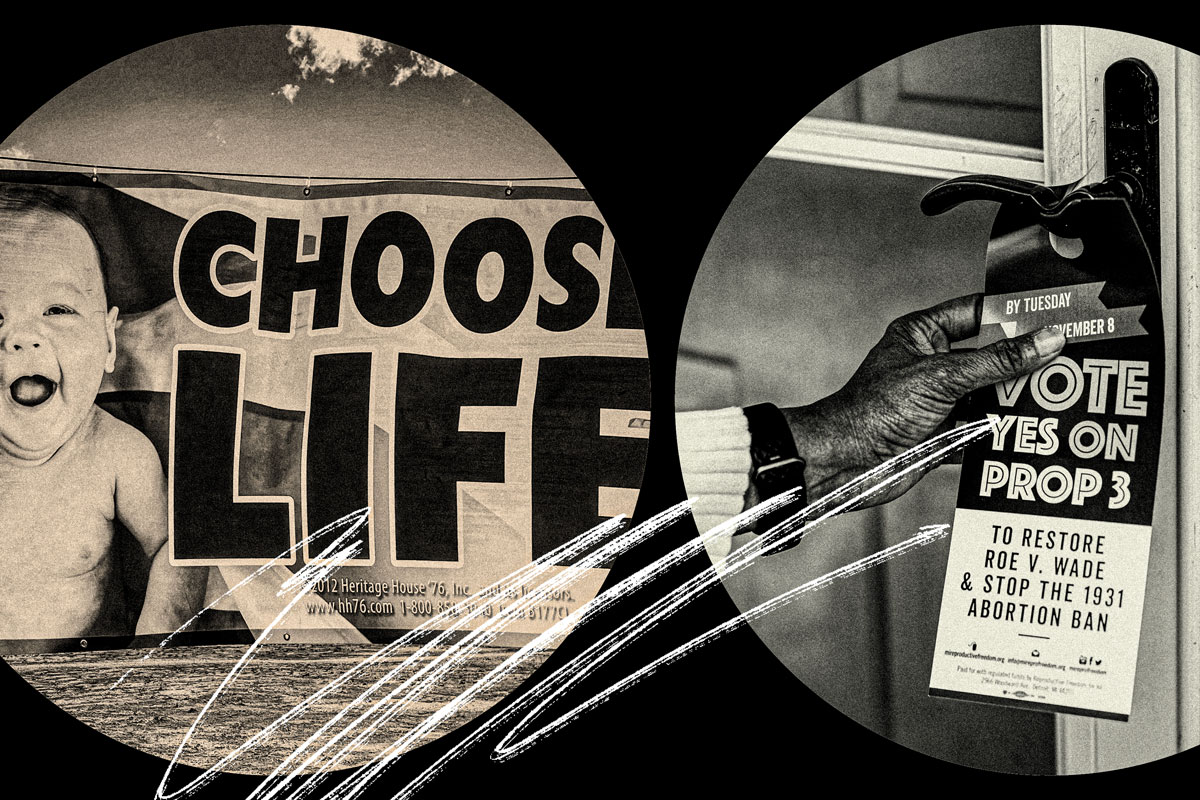

The week following Kansas’s unexpected news was an uncomfortable one for Republicans, accompanied by wide conjecture around whether abortion would have a significant impact on the upcoming midterm elections. These fears were substantiated by polls that began to show Democrats pulling ahead across the country. On September 28, 2022, a little over a month before the November midterms, there were still stirrings that the decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization would exact a cost from the party that had finally carried out its half-century long campaign to overturn Roe. But a month is a long time in an election season, and by the time the midterms rolled around the GOP had once again gained in the polls. Predictions of a “red wave” were ascendant and even Democrats tried to keep expectations low by reminding everyone that midterm elections almost always produced wins for the party not currently in power. In their podcast episode prior to Election Night, the editors of The National Review, led by Rick Lowry, predicted a great triumph for their party. They hardly mentioned abortion at all. The soaring inflation rate and still-high gas prices, they surmised, would propel them to victory.

Early exit polls suggested that abortion had mattered more to voters than Republicans had thought.

Of course, this is not what happened, and the story of what did is a story about race, and about who abortion restrictions really end up punishing. The first signal that abortion rights would be important in the election came when polling closed in swing-state Pennsylvania. Early exit polls there suggested that abortion had mattered more to voters than Republicans had thought. In Philadelphia, where a majority of Democratic voters pushed President Biden to victory two years ago, abortion was a key issue. As one female voter in the city put it “If, God forbid, something were to happen with my pregnancy and I needed to terminate, I want to make sure that that’s something that I’m able to do in the state of Pennsylvania.” That sentiment was a resounding one, particularly among urban Pennsylvania voters—a group that includes more minority women—and it was what propelled John Fetterman to victory over Dr. Mehmet Oz, handpicked by Trump and an abortion opponent. All five states that had ballot measures making it easier to ban abortion were defeated, including those in red states Kentucky and Montana.

As many articles have pointed out, Black women account for 40 percent of abortions in the United States. To understand the disproportionate share of abortions they need requires noting the country’s huge racial gap in maternal healthcare provision. As a 2018 study discovered, maternal mortality rates for Black women were shockingly high compared to white women. A Black woman in the United States is three times more likely to die during pregnancy or postpartum than a white woman. This is in many ways an inevitable result of the fact that Black population centers in the United States typically have fewer and more under-resourced health care facilities than white areas. These same areas are often food deserts where the lack of access to fresh and healthy fruits and vegetables is almost nonexistent. This leads to high obesity rates, which affect health outcomes and can lead to more complications in pregnancy as well. Rates of re-eclampsia and heart attacks connected directly to high BMI, as well as pregnancy-related diabetes, are five times higher among Black women than white women. And even when Black women do have access to the same resources and facilities as their white counterparts, studies have shown that doctors are less likely to take their pain and self-reported symptoms seriously, allowing sometimes-fatal complications going undiagnosed.

None of these numbers are new. They remind me of a question a white woman once posed to me during a public lecture on how violence against women inordinately affects Black and Brown women. “White women are abused too” this woman said diffidently. Her words are true, white woman are also abused but their white privilege means that they are better able to gather resources that can help get them out of the situation. The relative economic and social privileges that come with being white mean that even if they do not have resources themselves, they are far more likely to have family and/or friends who can help them in dire situations. Black and Brown women, including immigrants, do not have access to these resources. As a result, these women are the ones that must rely on public services, from transportation to shelters to health care.

When white women need abortions or any other kind of maternal health care, they are generally able to either obtain it without any trouble or, in the case of an abortion restricted state (like in one of the thirty states that intend to ban abortion post-Dobbs), they are statistically more likely to be have access to a solution such as travel to a state where the procedure may be legal than are Black women, most of whom receive maternal healthcare in a concentrated set of hospitals which provide a lower quality of care.

This knowledge of the Dobbs’s stakes was evident in the vote margins. A majority of white women once again voted for Republicans (by six points more than they had in 2018). Black and Latina women voted for Democrats. If any women helped stand up for abortion rights, it was clearly women of color. Given the obvious white supremacist leanings of the Republican Party, this means that a greater number of white women voted based on their race rather than their gender, prioritizing their continued ability to reap the advantages of white racial privilege in the future. This, they believed, was more important than the Supreme Court’s brutish reversal of Roe v. Wade and the direct challenged to female bodily autonomy.

Some have argued that white women, in voting for anti-abortion Republicans, voted against their interests. This is not correct. White women voted precisely if perniciously in their own interests. They voted, in essence, for the maintenance and entrenchment of the white privilege that they knew would continue to save them, and even to lift them up as model pathbreakers, CEOs, writers, lawyers, etc. as white men shared power with them. Greater access to birth control and their higher average age when giving birth made the need for an abortion less likely, while the myriad benefits of white privilege made it more easily available with a plane or car ride. Simply put, abortion access was not their problem, and so they voted Republican, punishing their Black and Brown sisters, even though they likely do not actually oppose abortion itself.

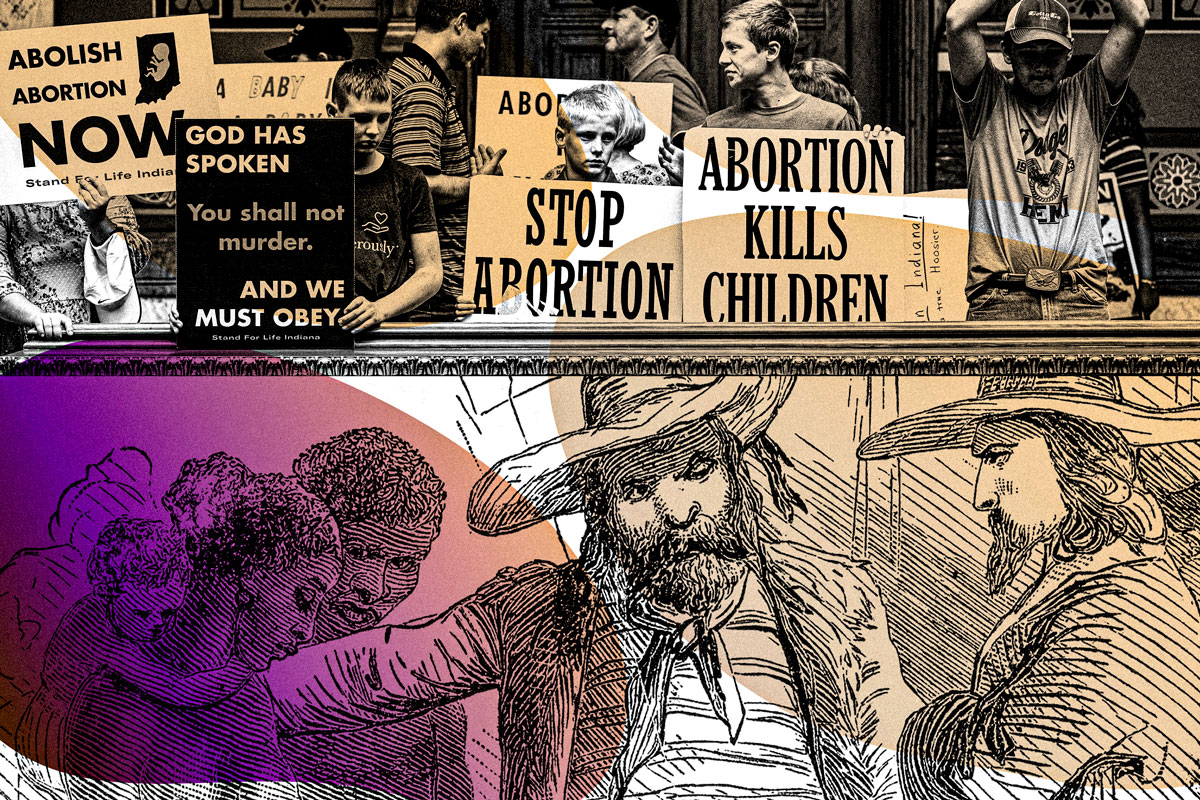

White men should also be held responsible. I have written here about what it was like to watch State Bill 1 pass in the Indiana Legislature, making the state the first to ban abortion in the wake of Dobbs. Not only was there palpable glee among the proponents who won that day, but I sensed the same sort of glee among GOP political analysts prior to the midterms. Abortion, it seemed to them, would never be an issue over which to grapple with voters—it had been merely a blip in the poll-verse, if anything a bone tossed to increase turnout among the most rabid factions of their base.

Abortion access was not their problem, and so they voted Republican, punishing their Black and Brown sisters, even though they likely do not oppose abortion itself.

Their disdain reminded me of a colonial example I encountered a few years ago. In the incident, which is recounted by Harvard feminist scholar Durba Mitra, a committee of old white men in colonial-era Calcutta considers the case of Kally Bewah, an Indian woman who was found dead in a thatched hut outside her home after an alleged abortion. Punishing Kally Bewah was out of the question—she was already dead—but these men found it necessary to examine her excised womb as a medical “example” of what they called the “ordinary” circumstances of Indian women. Indian women, the thrust of the discussion was, were far more likely to abort their babies, owing to some inherent criminal inhumanity. Abortion must therefore be criminalized in colonial India, they reasoned, even though it was not punished criminally in England itself.

This historic example from remains relevant today because it underscores the fact that casting women of color voters as criminally inclined to have abortions is not a new tactic but a very old one. These voters recognize that one intent of banning abortion is to create ever more opportunities to criminalize women of color; these women, who may not have the resources to travel somewhere where abortion is legal, will now be easier for the state to prosecute and jail. White women, meanwhile, will continue to benefit from the voting choices of women of color but also from cultural tropes that portray them as more maternal, hence unwilling to demand legal abortions, and less likely to attract the attention of police and government agencies.

The qualified success of Democrats in the midterm elections is a good outcome. So is the defeat of the five ballot measures that would have led to criminalization of abortion in those states. At the same time, the Dobbs verdict is still the law of the land. If American women want to regain the right to make decisions about their own bodies, there will have to be organized and they will have to be strategic and they will have to be unified across color lines. The only route left is to demand federal legislation that protects the right of women to make their own choices—and women of color should not have to fight this battle alone.

Rafia Zakaria is the author most recently of Against White Feminism (W.W. Norton, 2021). She is also a columnist for The Baffler and Dawn (Pakistan).