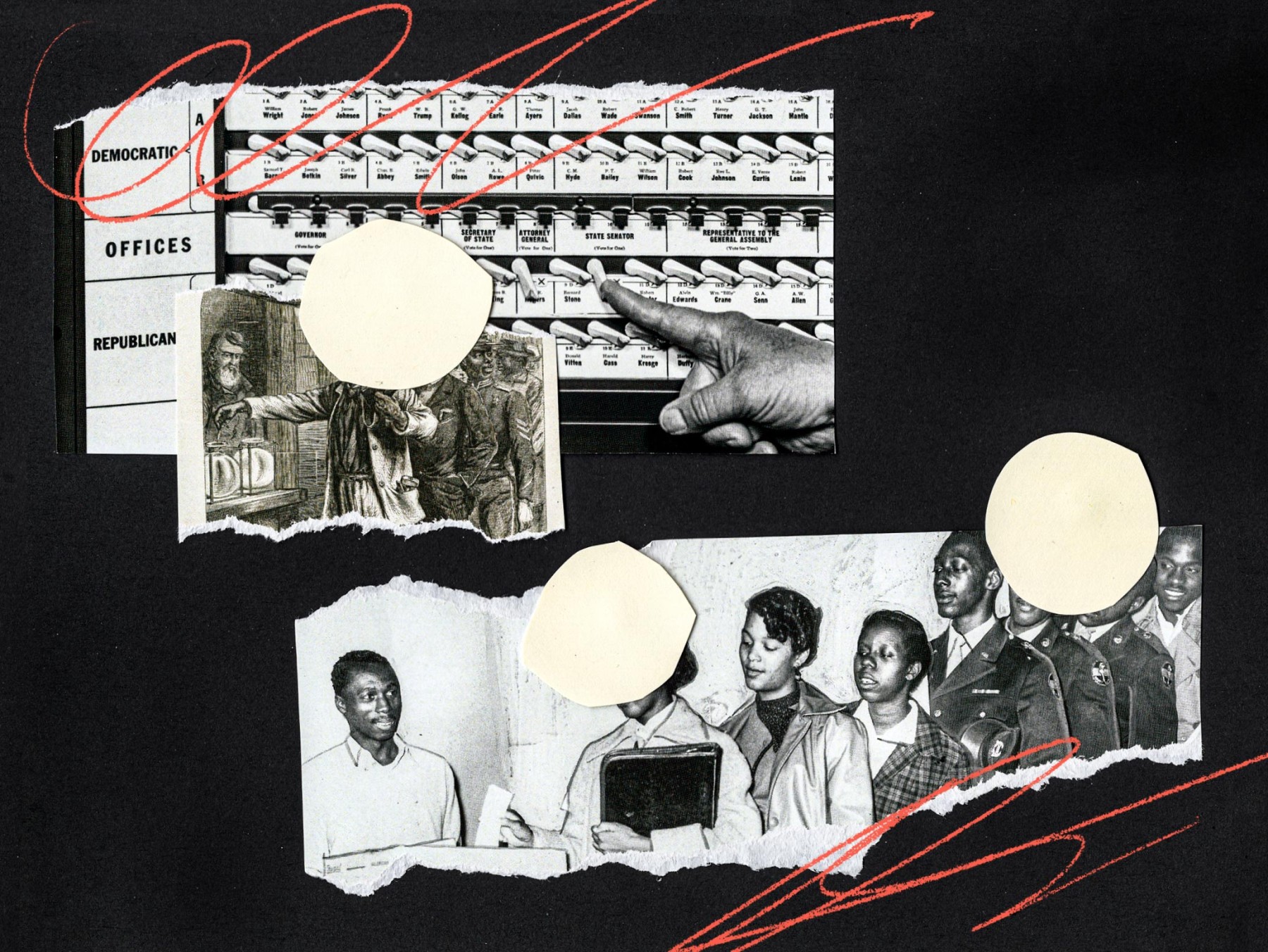

Momentum is inarguably gathering behind Democratic candidates in several key midterm races. Nothing is certain until the final votes are counted, and Republican election officials around the country are seeing to it that the process of counting is as heavily politicized as any other aspect of campaigning. Yet what looked like an impending disaster for Democrats in Congress—and by extension, the beleaguered cause of democracy in America—as recently as June now looks much less foreboding.

What changed? As many commentators have suggested, the Dobbs decision from the Supreme Court has centered conservatives’ deeply unpopular anti-abortion politics in an election Republicans had hoped to define with ugly, silly moral panics (such as the ongoing assault on critical race theory, and the alleged transgender brainwashing of children) and inflation. Senate Democrats overcame Joe Manchin’s obstructionism to find a version of the president’s floundering climate policy proposals that they could pass through reconciliation. The White House followed that up quickly with executive action on student debt, fulfilling a key Biden campaign promise.

If it’s an exaggeration to say that suddenly everything is going right for the Democratic party, it’s easy to understand why some liberals are moved to voice something not unlike optimism. Still, none of these policy accomplishments, nor any amount of self-sabotage by a Republican party hellbent on nominating lunatics and reminding voters of their repellent views on abortion, same-sex marriage, and other key issues, can overcome the long-term risks courted by the failure to pass meaningful voting rights reforms since Biden swept Trump from the White House.

The president has promised that these reforms are one of the many goals on which the Democrats will be poised to deliver if they can expand their Senate majority to something beyond the bare 50-50 split they currently hold. Perhaps. The long history of using voting rights—and particularly the rights of Black voters who almost inevitably become the focus of efforts to disenfranchise—as a bargaining chit in Washington suggests that meaningful action on this front is anything but certain.

Until the political process demonstrates that it is willing to treat voting rights as a non-negotiable precondition rather than a political consideration on par with soybean subsidies, progress is unlikely.

Until the political process demonstrates that it is willing to treat voting rights as a non-negotiable precondition rather than a political consideration on par with soybean subsidies, progress is unlikely. To understand why, we need to travel back to 1890, when the Senate considered but ultimately rejected the Federal Elections Bill, also known as the Lodge bill, or the Voting Rights Act of 1890.

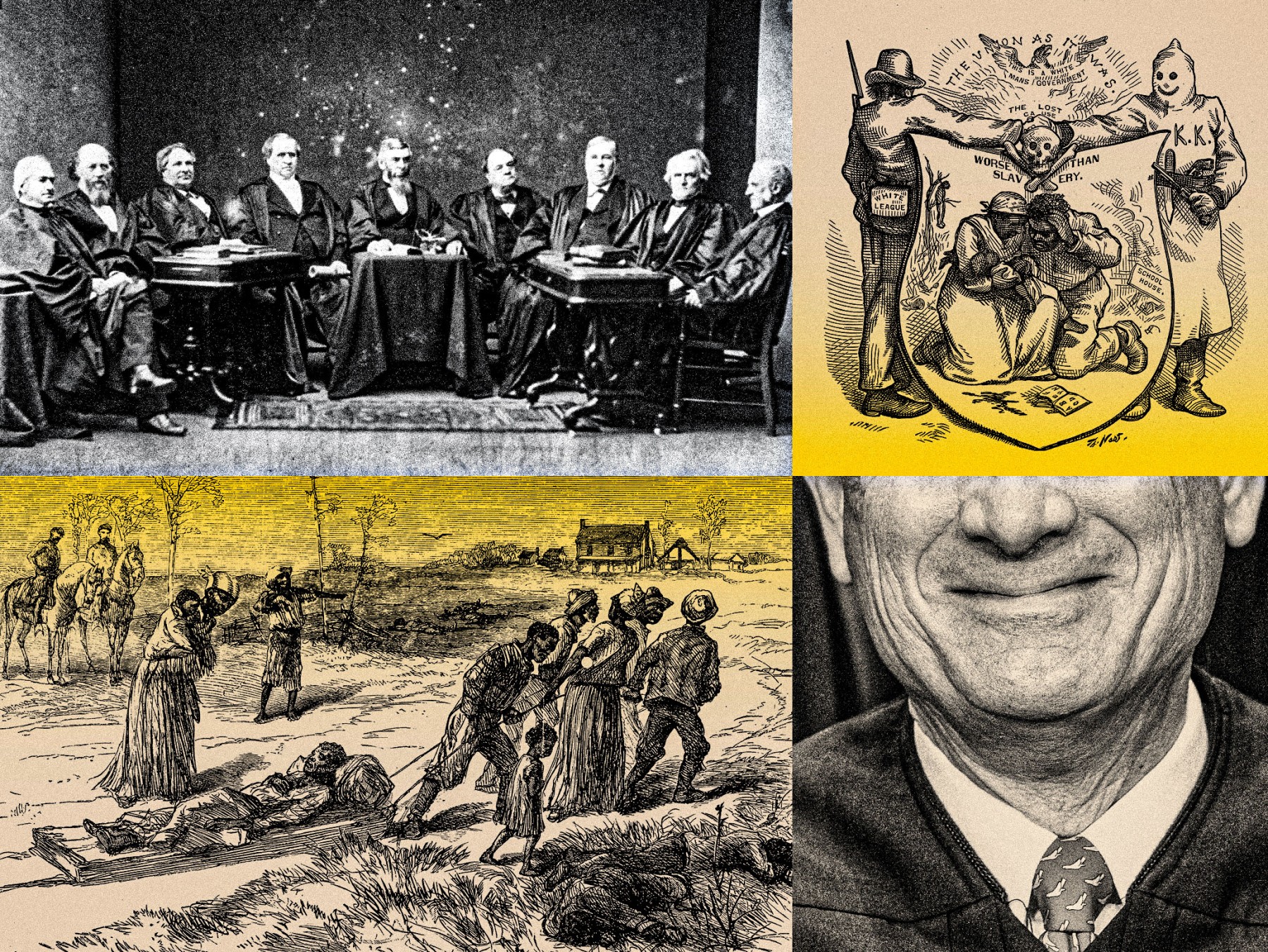

In the wake of the Civil War, northern Republicans’ commitment to protecting Black voting rights in the South via Reconstruction faltered and ultimately collapsed with the political compromise that resolved the tainted presidential election of 1876. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the Constitution seemingly guaranteed suffrage irrespective of race (women’s voting rights were but an afterthought in national politics in that era). Yet southern governors, state legislatures, law enforcement, and domestic terrorist organizations effectively combined to ensure the continued disenfranchisement of Black citizens.

When Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected to the White House in 1884, Radical Republicans—the most vociferous advocates of Reconstruction and the necessity of Federal enforcement of the post-Civil War amendments against recalcitrant Southern state governments—were determined to use the powers of the federal government to face down this vicious assault on the Black franchise. Cleveland, a New Yorker, was considered less polemical than Southern Democrats—but leaders of the national Democratic party still believed that they could count on him goals to disenfranchise Black voters to aid Republican electoral prospects. Under the direction of Senator William E. Chandler (R-NH), Radical Republicans began to workshop legislation to guarantee federal enforcement of the 15th Amendment. It mandates that “(the) right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude”—and, as many amendments do, it noted that Congress “shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

Chandler, in tandem with neo-abolitionist Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge (R-Ma.), took the latter statement at its word and got to work. When Republican Benjamin Harrison of Indiana, an advocate of federal enforcement of the post-Civil War Amendments, won the presidential election of 1888, the Republican-majority Congress pushed forward with a nascent “Voting Rights Act” that attempted to do in the Gilded Age what the federal government could not deliver until 75 years later. The Federal Elections Bill of 1890 was introduced by Northern Republicans confident that their Senate majority was about to make successful passage of that and many other bills a foregone conclusion.

In the background, a long-term Republican effort to grant statehood to newly organized plains and western states was culminating as Harrison entered the White House. In 1889 and 1890, six states—North and South Dakota, Montana, Washington, Idaho, and Wyoming—were added to the union, advancing Republicans’ partisan desire to reduce Democratic power in the Senate. Since Democrats’ power was regional, focused heavily in the former Confederacy, southern Democrats understood that freezing the number of states in the union was a matter of political survival. Radical Republicans, conversely, understood that granting statehood to existing territories would undercut Democratic power in the minoritarian Senate.

Thus at the outset of the 51st Congress, the Republicans had a small Senate majority that soon bulked up into a near-supermajority (51-35 by late 1891) as new state legislatures added Republican senators. (Senators would not be popularly elected until 1913.) Bolstered by this influx, Northern Republicans pulled few punches as they set about crafting what became the Lodge bill. It gave the federal government sweeping oversight of elections for the House of Representatives—balloting that was then strictly under the supervision of state and local election officials all too willing to enforce Jim Crow laws suppressing and terrorizing the Black vote rather than federal laws to safeguard it. Federal courts, under the Lodge bill, would have the power to appoint election supervisors if 500 citizens of any House district claimed by petition that their constitutionally guaranteed voting rights were being denied locally. Most crucially, and controversially, these supervisors would have the power to call in United States Marshals to enforce election laws when local law enforcement and elected officials refused to do so. It was, in short, a Radical Republican wish list representing the spirit of what Reconstruction was originally intended to accomplish.

Southern Democrats decried the bill in predictable and apoplectic terms. They insisted that it was but the latest instance of Northern meddling in a culture that only (white) Southerners understood properly. They rhetorically rebranded it as the “Lodge Force Bill” to communicate the sense of grievance and victimhood at the hands of a cruel federal government. This was, and remains, a central plank in the white southern leadership caste’s steadfast allegiance to “states rights” politics. Lodge saw in real time that Southern Democrats’ own arguments against the bill amounted to little more than the promise of rebellion, nullification, and racial terrorism. He took to the pages of The North American Review in 1890 to explain as much: “Southern Democrats declare that the enforcement of this or any similar law will cause social disturbances and revolutionary outbreaks. As the negroes now disenfranchised will not revolt because they receive a vote, it is clear, therefore, that this means that the men who now rule in those States will make social disturbances and revolution in resistance to the laws of the United States.” The modern echo of that argument, given the political realities of 2022, is difficult to miss.

It takes some imagination to grasp what a pivotal, if rarely remembered, inflection point in American history this bill represented. Some Since the Lodge bill dealt specifically and narrowly with elections to the House, additional legislative or judicial action would have been necessary to guarantee voting rights in all other elections.of the reforms enshrined in the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts of the Lyndon B. Johnson administration very nearly became a reality seven decades earlier. Creative writers of alternate history fiction have here a scenario rich with possibilities. The political trajectory of the nation, and the Southern states in which disenfranchised Black voters would outnumber those interested in maintaining white supremacy, would have been radically different.

But it was not to be.

In the twenty-five years since the end of the Civil War, the nation’s political establishment had lost much of its zeal for upsetting the status quo of racial hierarchy. Respectable outlets of the intelligentsia like The Nation and Harper’s advanced arguments that perhaps it was best to let the issues that animated Reconstruction lie. Even Republican-oriented newspapers ran editorials admitting that the law was within Congress’s authority to pass but should be deferred lest it lead to bloodshed. See DeSantis, Vincent. Republicans Face the Southern Question, 1877-1897. Johns Hopkins, 1959: 199-201.White fears, in 1890 as in 2022, took precedence over Black rights.

Crucially, not all Western and Northern Republicans shared the Radicals’ enthusiasm for enforcing the 15th Amendment by force. True, the 1888 Republican platform endorsed “effective legislation to secure the integrity and purity of elections”—but many congressional Republicans stopped well shy of endorsing voting rights as a top priority. Southern Democrats, sensing the opportunity to chip away at an otherwise lopsided Republican Senate majority, sprung into action to make deals with various Republican factions to undermine Lodge.

Northern Republicans sought Democratic votes to push through the Tariff Act of 1890 (called the McKinley Tariff, after its House sponsor who would be president within the decade). And Western agrarian Republicans were eager to pass the Sherman Silver Purchase Act (1890) to promote a national currency no longer solely reliant on the gold standard. In both regions, these locally important economic issues took precedence over almost any other political controversies of the day. Farmers struggling under mountains of debt sought “free silver” to increase the money supply and ease their repayment burdens, while Northern urban financial and industrial interests strongly embraced protectionist trade policies sure to be bolstered by stiff tariffs. To the extent that these factions supported election reforms to secure Black voting rights, that issue was easily consigned to a secondary position behind their more immediate self-interest. The terrorization and oppression of Southern Black voters was abstract in Wyoming or in New York, an issue that affected other places and other people—other Black people, specifically, who were easy for white politicians catering to mostly-white voters to throw under the bus.

If—and it remains a big if—Democrats manage the historic feat of squeaking past the midterms with small majorities intact, there can be no greater priority than advancing their stalled efforts to pass voting rights reform.

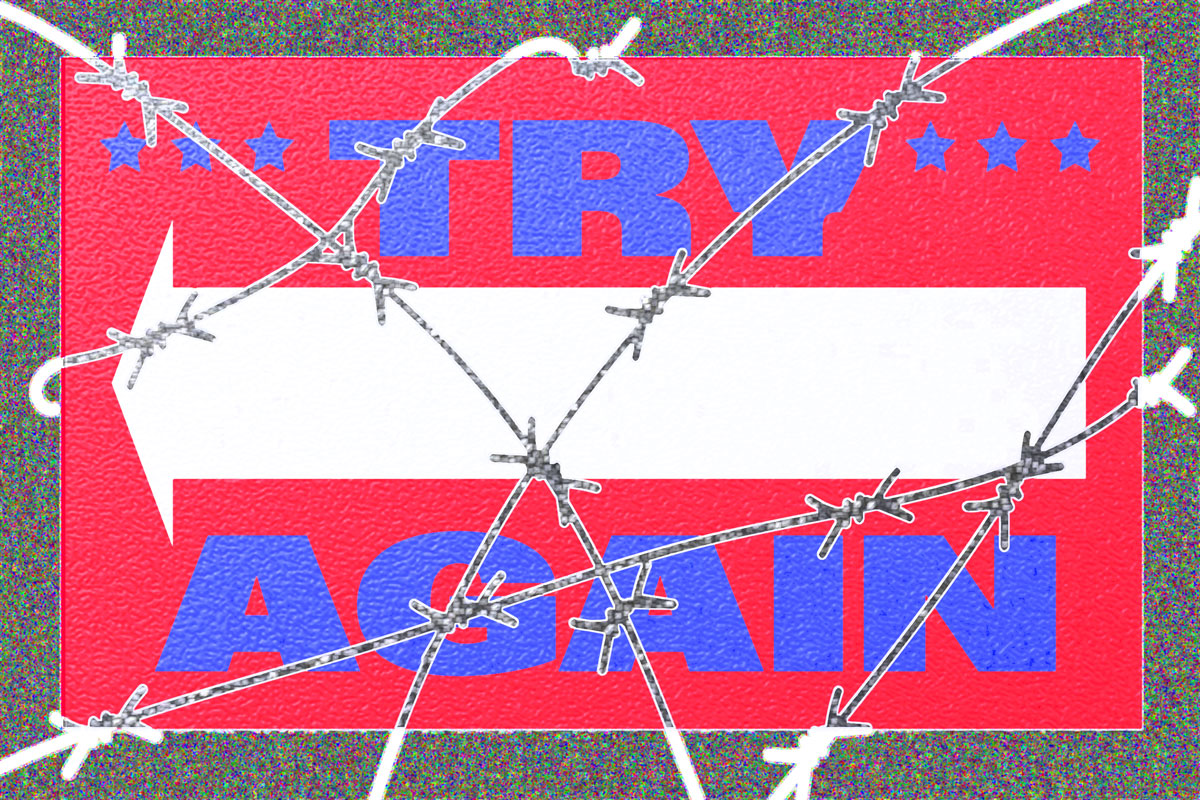

The final nail in the Lodge bill’s coffin also resonates today. As Jamelle Bouie explained last year in the New York Times, the ultimate failure of the Bill lies at the feet of the Senate filibuster. After the Republican-led House passed it by a slender five-vote margin, the Senate began debate and demonstrated in short order just how effective it is shoring up the status quo. Despite the Republicans’ healthy Senate majority, just enough individual Republicans were swayed to prevent a three-fifths vote for cloture—i.e., a vote to override the filibuster. The potentially transformative legislation died the prosaic, procedural kind of death that legislation so often does in the Senate. It died because of a rule that needn’t exist—the Senate is by its very makeup counter-majoritarian, and needs no additional layers of rules to make it more so—after individual senators for whom Black voting rights were ultimately not that important casually exchanged them for other political priorities.

That the United States and American politics are vastly changed since 1890 is unquestionable. Yet the death of the Lodge bill demonstrates how little some things have changed.

Senator Kyrsten Sinema has prominently advanced the nonsense argument that any action on voting rights must be bipartisan. With the Lodge bill, its proponents understood from the moment the idea was conceived in 1884 in response to Democratic nominee Grover Cleveland winning the White House that any legislation that would effectively protect Black voting rights would be slandered as partisan. As the historian Thomas Adams Upchurch emphasizes in Legislating Racism: The Billion-Dollar Congress and the Birth of Jim Crow, any such bill would “be by definition partisan and sectional” because “Democrats and white southerners (would call it) a ‘Force Bill’ no matter what it actually said, for by their preconceptions it would be written strictly to force. . . .Republican rule upon the South.” Radical Republicans behind the legislation saw Southern concern-trolling (a term not yet in use in 1890, of course) for the attempt to dilute and undermine the bill that it obviously was. That the lessons of history are so utterly lost on some of today’s legislators is inconceivable; appeals to the necessity of bipartisan or nonpartisan solutions are transparently anti-democratic, or at best provide useful cover for anti-democratic motives.

Republicans around the country have been engaging in all manner of voter suppression for decades, and they have not been subtle about their intent even as they bury their goals under mountains of rhetorical sludge about (nearly nonexistent) voter fraud. But that was merely a warm-up for the current Trump-led push to radically empower state and local election officials driven by little more than their own febrile conspiracy theories to invalidate votes. This militant corps of right-wing intimidators is poised to alter after-the-fact election outcomes wherever voter suppression fails to achieve outcomes favorable to the right. Appeals to the conscience of “good Republicans” are as likely to change their approach as any other wishful thinking. History suggests that the Democratic Party—the party of the incumbent president—should lose ground in the upcoming midterm congressional elections. Unbelievably, they may instead be poised to expand their hold on the Senate, slightly. Holding the slim House majority will be an even more difficult task, but it’s one that no longer looks impossible nor necessarily implausible. The Republicans, it seems, have done everything possible to ensure that even voters disappointed with years of ineffectual Democratic leadership have reasons to “vote blue no matter who” in November.

If—and it remains a big if—Democrats manage the historic feat of squeaking past the midterms with small majorities intact, there can be no greater priority than advancing their stalled efforts to pass voting rights reform—and to revive the District of Columbia statehood bill that passed the House behind President Biden’s endorsement and floundered, predictably, in the Senate. The lessons of 1890 are many, but none is clearer than the need to use every institutional tool at the Democratic party’s disposal to disempower its anti-democratic opponents. Because there can be no delusions about what the Republicans are and what they are trying to do. They are, like their conservative Southern Democrat forerunners in the nineteenth century, openly trying to achieve a stranglehold on political power independent of the outcomes of a fair election with universal suffrage. If the Senate filibuster remains an insurmountable obstacle, we have all the lamentable historical evidence we need to remind us of the consequences of prioritizing norms and legislative procedures over the rights and lives of actually existing human beings.

Ed Burmila is the author of Chaotic Neutral: How the Democrats Lost Their Soul in the Center (Bold Type Books).