Detroit has been represented by at least one Black member of Congress since 1955. That’s four years before Berry Gordy founded Motown Records, three years before Ozzie Virgil became the first Black man to play for the Detroit Tigers, and 17 years before General Motors hired its first Black automotive designer in 1972. The tradition of Black congressional representation in Detroit predates even the launch of the Edsel and the gospel album recorded here by 14-year-old Aretha Franklin.

Now that long, proud run is nearing an end. After this November’s elections, Detroit—nearly 80 percent Black, the largest percentage, by far, of any major American city—will likely be left without any Black representation in the U.S. House. An era that covered parts of eight decades, and the careers of heavyweights such as Rep. John Conyers and Rep. Carolyn Cheeks Kilpatrick, a former chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus, will close.

How is this possible? This is a story about redistricting, good intentions and unintended consequences, about population loss and suburban growth. It’s about the cold, unforgiving math of our political system, and the way overcrowded primaries divide votes and distort outcomes. And it points to the electoral reforms we desperately need—especially ranked-choice voting, but also an end to single-member congressional districts—if we’re to avoid having the nation’s largest Black majority city lacking representation that looks like the majority of its citizens.

In a winner-take-all primary, Black voters could be punished for producing multiple candidates and having to choose among them.

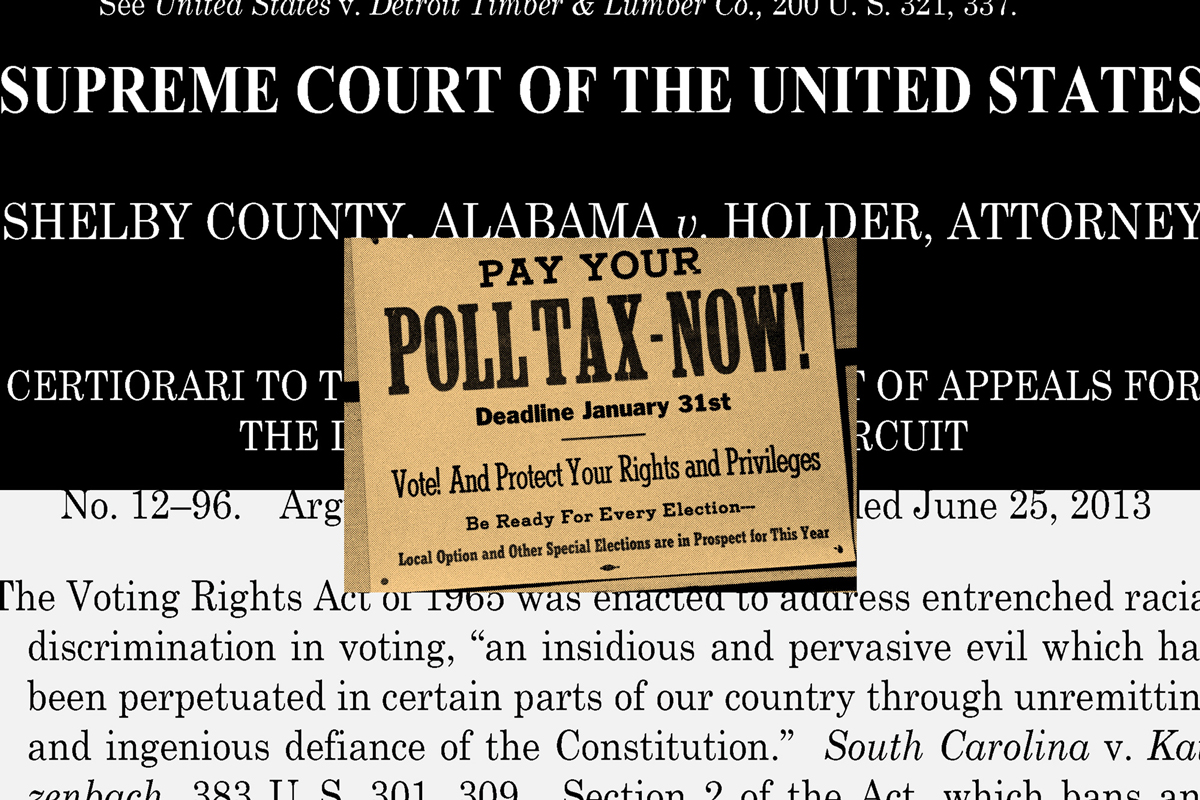

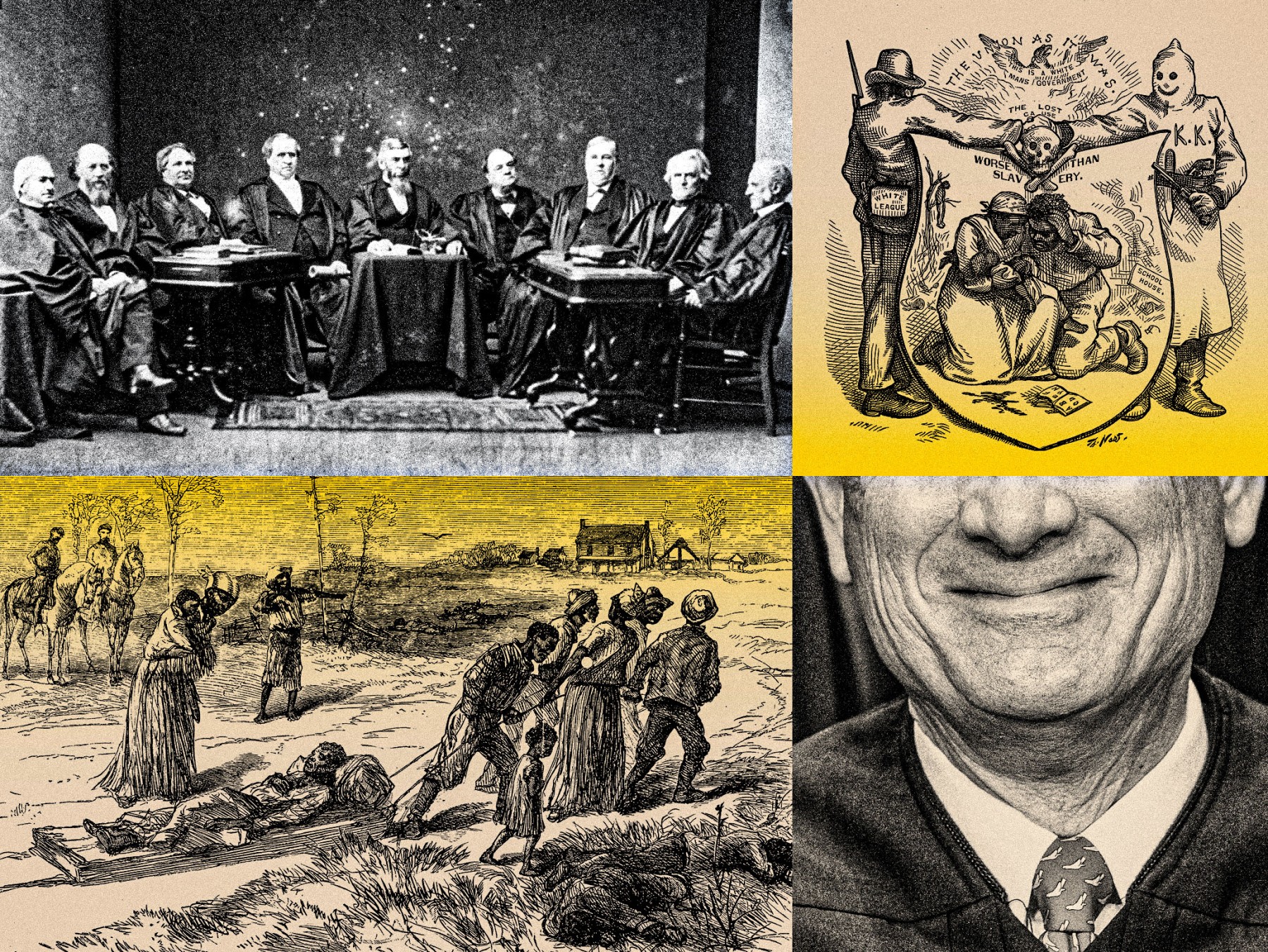

Let’s start here: Every congressional map in the nation gets redrawn every 10 years, post-census, to account for population changes. When Michigan’s maps were redrawn in 2011, Republicans held the pen and sought as many red districts as they could get away with, while also drawing up the fewest possible that might go blue.

Any gerrymander involves two key tools: Cracking and packing—the art of either spreading the other side’s voters thinly across many districts, or packing them into as few as possible. In Michigan, Republicans packed Black voters—who tend to vote heavily for Democrats—into two wildly contorted, even snake-like districts, then carved the Detroit suburbs into a pinwheel of whiter, GOP-friendlier seats.

Michigan’s 13th (56 percent Black, 34 percent white) and 14th districts (57 percent Black, 31 percent white) overwhelmingly elected two Black representatives to Congress for much of the decade, usually with 80 percent or more of the vote and little organized opposition. The gerrymander worked as expected—and with so many blue voters packed into those two seats, Republicans held nine of the 14 seats in this bluish swing state for several consecutive election cycles. The state legislature, drawn with the same intent, also produced reliable GOP majorities, even when Democrats won more votes.

Frustrated citizens, recognizing correctly that their votes didn’t really matter, demanded a fairer approach to redistricting. In 2018, 61 percent of Michiganders supported an amendment to the state constitution that would take the line-drawing power away from politicians and put it in the hands of an independent citizen commission that included voices representing many ethnicities, ideologies and geographic backgrounds.

The members of that citizen panel did a tremendous job. They held public hearings across the state, worked openly and transparently, consulted experts on the Voting Rights Act—and drew the fairest and most equitable state legislative and congressional districts that Michigan has seen in several decades. Nonpartisan experts graded the maps highly for partisan fairness and competitiveness. This fall, the party that wins the most votes will, in almost every likelihood, win the most seats.

And yet: This decade Michigan lost one of its seats in Congress to faster-growing states. Detroit’s population plunge accelerated, as the census recorded 10.5 percent fewer residents. Some of that decline could be attributed to Black residents moving from Detroit into its nearby suburbs. Conyers, a five-decade veteran Black lawmaker, died. And the Voting Rights Act experts retained by the commission produced a study showing that there was enough “crossover” or coalition voting in metro Detroit such that Black voters could still elect a member of their own choosing even if the overall Black voting-age population was less than 50 percent.

But those experts missed something crucial. Black voters, along with white crossover voters, might still elect a Black candidate in the general election. Yet a primary election in a Black political stronghold, where several strong candidates might seek office and divide votes, could be something else entirely. Black voters, in that case, could be punished for producing multiple candidates and having to choose among them.

This shouldn’t have been a theoretical concern. It’s exactly what happened in the 2018 primary, after Conyers’ retirement. Four Black candidates—including the Detroit city council president, a state senator, a former state representative, and Conyers’s son—earned 55.6 percent of the primary vote among them. The winner, Rashida Tlaib, won the race with just 31.2 percent of the vote, defeating Brenda Jones, the council president, by 900 votes.

The same thing happened in the Democratic primary this year. Eight of the nine candidates for the new 13th district seat were Black. They divided 71.7 percent of the vote. The winner, Shri Thanedar, captured Michigan’s last-remaining Black seat with 28.3 percent of the vote.

If Michigan adopted ranked-choice voting for primary elections, and required any winner to earn at least 50 percent support, there would be no spoilers.

There’s a better way to do this—one that would allow more Black candidates to run without fears of dividing the vote, provide fair representation to the communities represented by Tlaib and Thanedar, and also guarantee that more votes mean more seats.

If Michigan adopted ranked-choice voting (RCV) for primary elections, and required any winner to earn at least 50 percent support, there would be no spoilers. RCV works much like an instant runoff; if no one earns 50 percent on the first round, the last-place candidates are eliminated and second choices come into play. This would allow multiple Black candidates to run from a community that has many potential leaders, without fear of vote splitting. And while Thanedar, for example, assured Black voters he would be their representative too, RCV would have pushed him to campaign more within Black communities and work for second choices, rather than best a deeply divided field with a mere 28 percent plurality victory.

Better still, we could end gerrymandering altogether and fix one of the core problems in our politics if we moved from single-member congressional districts to larger, multi-member seats, under a plan currently before Congress called the Fair Representation Act. Under this measure, Michigan, for example, would have the same 13 members of Congress—but they’d be elected from districts of five, four and four members. A five-member district with metro Detroit and its suburbs at its heart would likely elect at least two Black Democrats, Tlaib (one of only two Muslims in Congress), and perhaps as many as two Republicans.

Under a more proportional system such as this, communities of color and communities that include diverse political perspectives are not pitted against one another. Instead, everyone receives the representation they deserve, according to the number of votes they earn. The side with the most votes would receive the most seats, But everyone would have a voice. This would put an end to our poisonous zero-sum, winner-take-all politics, in which politicians cater to their base, by providing strong new incentives for leaders to talk to every voter and work together in Washington.

It’s outrageous that Detroit lacks any Black representation in Congress. But it’s an outrage that makes clear how damaging plurality primaries and single-member districts have become. Detroit’s story shows how the imbalances and vote-rigging that plague our voting system distort and interfere with equitable representation—and vividly points up the harm they create for voters who ought to be able to choose among multiple Black candidates without fearing that their community will lose representation altogether. Fortunately, it’s an outrage that can be fixed.

David Daley is the author of Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn't Count and Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy.