Diary of a Targeted Teacher

It’s not even Labor Day, and we teachers are tired. At least I am.

I begin this new school year already tired of teachers committing to the most fundamentally important and urgent work of any civilization—educating its young people—while simultaneously being demonized, ridiculed and forgotten by those who have no idea what things are actually like in a classroom.

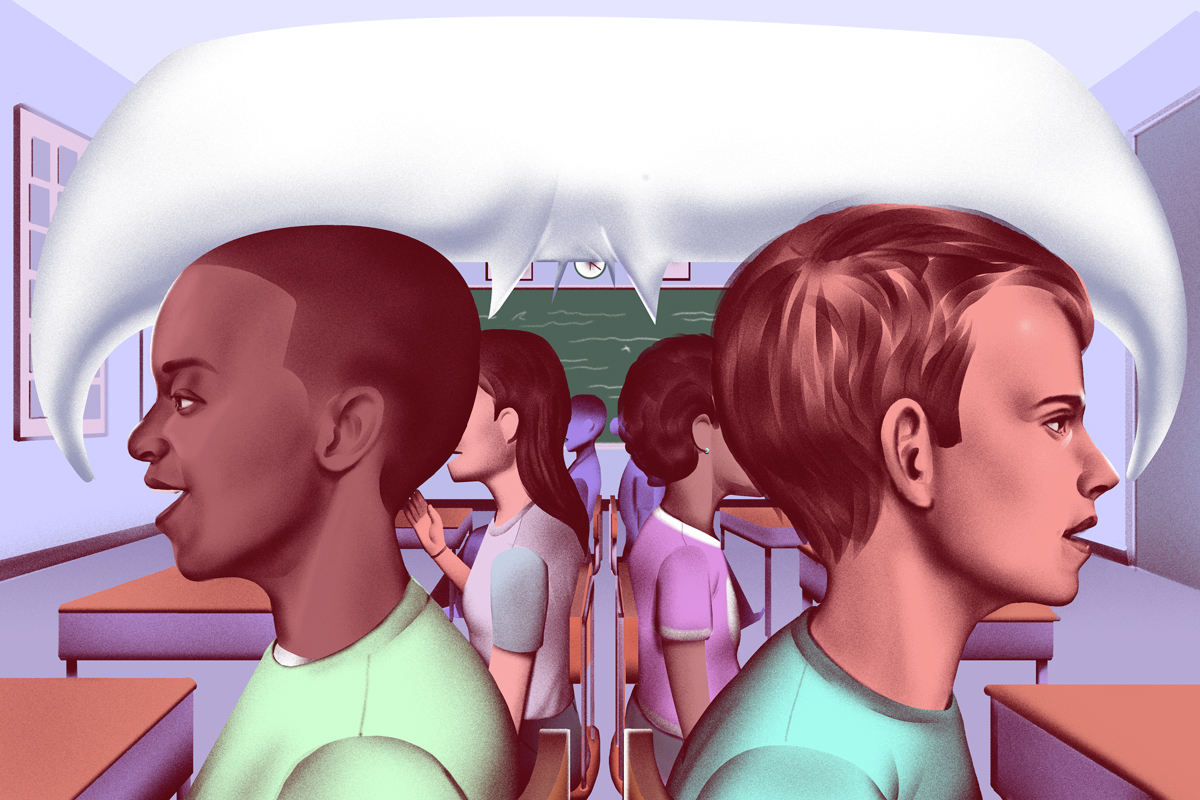

American teachers are projected upon in a thousand ways. We’re labeled as indoctrinators, provocateurs, and idiots; meanwhile, our students are exhausted, starving for meaning, starving for lunch, starving for security in a culture that seems to oppose them at so many turns.

I am tired of the weight that’s strapped onto us before we even step into our classrooms. The feeling that we’re always expected to pull duty as political puppets burdens us, making it seem as if our professional lives were nothing but fodder for political manipulation and cultural warfare. We are all still worn down and wounded from teaching through a pandemic while also trying to survive as living, breathing humans in an American system whose violence manifests itself in so many ways—from school shootings to the fear-based banning of lessons and books. Before all these challenges, we often find that teaching requires more than we have to offer.

I begin to quietly wonder: is this worth it? How long can I keep this up?

I am tired of the extraneous nonsense that seems to get louder, polluting the public square with inanity and insanity. America feels like the Tower of Babel, where so many of our common virtues and social-contract agreements seem split asunder.

Our need for full reservoirs of civic truth and fearless critical inquiry has never been greater, yet our reservoirs have never been more depleted.

“The story of Babel is the best metaphor I have found for what happened to America in the 2010s and for the fractured country we now inhabit. Something went terribly wrong, very suddenly. We are disoriented, unable to speak the same language or recognize the same truth. We are cut off from one another and from the past,” Jonathan Haidt writes in the Atlantic.

Then, America asks us to clean it all up while situating us smack-dab in a system that often contributes to the very mess we are charged with cleaning.

What do I mean by the mess? To begin with, it’s the dissolution of cognitive thinking, critical citizenry, and loving wisdom—the Tik-Toking of childhood innocence and quiet, a materialism that commodifies the needs of the spirit. As Haidt suggests, there is the disruption of central truths, even at the most basic civic level. Could half our graduates even pass a 100-question naturalization test? I doubt it. And my prep school calls itself prestigious.

“How smart does our populace have to be to remain a democracy?” one friend asked.

Our need for full reservoirs of civic truth and fearless critical inquiry has never been greater, yet our reservoirs have never been more depleted. I know teachers with literal bladder infections; they are unable to get to the bathroom during the school day because their classes are so large, and help and free time are so scarce. This is one example of thousands.

Sometimes, it becomes too much. In William Melvin Kelley’s A Different Drummer, a Black farmer in the post-Reconstruction South wages his own private revolution. One day, he slaughters his livestock, salts his fields, burns his house and simply walks away. He leaves. His protest then spurs a mini-Black exodus, as other Black families follow. The entire novel is told through the lens of different angry, defensive, and confused white residents who cannot understand his actions.

I daydream about a teachers’ version of this. Perhaps it’s already occurring. More than half of American teachers are considering leaving, according to the National Education Association, with higher percentages among Black and brown teachers.

We are undergoing a trial by fire, a melting away of the unessential parts of our careers until we are left with one core question, best expressed by The Clash decades ago: Should I stay / Or should I go?

I do not fault any teacher who leaves. One day, I will walk away, too.

Yet for those who stay, we must squarely face our deep motivations. Doing so may help us find a more solid ground upon which to stand.

Perhaps we begin here: with love. Love has always been the most latent force in any classroom. Awakening it turns the classroom experience into something unforgettably transformative; the lack of it turns education sour and irrelevant. Love is not sentimental or maudlin. The love of which I speak is the transcendent, active love that seeks the good in difficult situations—a love that sees our students as repositories of wholeness, that seeks to activate and encourage that goodness in them.

This love is not necessarily a feeling. We may be exhausted, pissed (or need to piss!), run down and bitter, yet we still teach with love every time we show up with the intention of aiding and affirming our students. As many have said, love acts as a verb more than a noun.

“The word ‘love’ is most often defined as a noun, yet all the more astute theorists of love acknowledge that we would all love better if we used it as a verb,” writes bell hooks in “All About Love: New Visions.”

As the poet Galway Kinnell reminds us:

[s]ometimes it is necessary

to reteach a thing its loveliness,

to put a hand on its brow

of the flower

and retell it in words and in touch

it is lovely

until it flowers again from within, of self-blessing

True education must always be countercultural, offering exit ramps from a world that smells seductively like demise into a more beautiful, effective, and whole existence.

Teaching reminds students of their loveliness, goodness, and inherent power. When we remind our students of their goodness, we awaken their intelligence. True education must always be countercultural, offering exit ramps from a world that smells seductively like demise into a more beautiful, effective, and whole existence. Maybe, just maybe, our students can find even the smallest taste of acceptance, care, and ease in our classrooms, where they meet a discipline always motivated by best-interest thinking, kindness and wisdom.

In this way, teachers begin to embody wise American elders, and while the rest of society may ignore this means of grounding ourselves in a shared quest for knowledge and understanding, we can taste the fruits of giving and receiving love through our teaching. The classroom then becomes a virtuously closed system; we are less dependent on the outside world, administrators, or school boards for validation.

No, love may not cure bladder infections, too-full classrooms, or too-empty salaries. And no, I cannot transform American education. Yet I can transform my own classroom, salting down irrelevant, useless dogma and practices, walking away in my own private rebellion from whatever pedagogical delusions I practice. Real education may happen in institutions that range from vocational schools to the Ivy League. As long as the movement is towards freedom and away from captivity, real education may happen in an HVAC 201 or in Philosophy 101.

Within those moments, we create and share a new energy. I feel it, the students feel it, even our ancestors feel it. Such teaching has always been cast as a pedagogical container for freedom, and while few schools are designed for freedom, we as teachers still operate within boundaries that offer us many chances each day of micro-liberation.

The tension contained within these boundaries and our raging school wars may help ultimately to remind us of why we teach, the potential within our teaching, and our own loveliness.

I do not know any other way to teach than this. I only hope that I—and everyone else struggling with these core elements of the real curriculum before us all—will be allowed to keep doing it.

Willie Randall is the pseudonym for an American educator who’s taught race and racial theory at multiple schools in multiple states.