On the morning of Easter Sunday, 1873, they rode toward Colfax, the county seat of Grant Parish, located alongside the Red River, a North-central Louisiana settlement in a region of cotton plantations. In all, they numbered around 165—Klansmen, the local White League, half of them Confederate veterans, some officers—all of them armed for the next fight. They paused at a sugar house not far from town and refashioned a cannon into a deadly field gun. And before they made the final march to the Colfax courthouse, where some five dozen Black men had gathered inside to defend the local, multi-racial officials appointed after Republicans were certified the winners of a violently contested state election, a local Klan leader sought to inspire his men for the battle to come. “Boys, this is a struggle for white supremacy,” said Dave Paul. “God only knows who will come out. Those who do will probably be prosecuted for treason. And the punishment for treason is death.”

Not long after, the vigilante mob surrounded the courthouse, launched cannons, set the building aflame, and drove the Black men outside. Their subsequent surrender launched an evening of bloodshed, hangings, and massacre. When a riverboat anchored in Colfax later that evening, its passengers tripped in the dark over mutilated bodies, “shot almost to pieces,” as Charles Lane writes in his jaw-dropping history The Day Freedom Died. Altogether the massacre at Colfax claimed somewhere between 60 and 153 Black lives, and bystanders reported that they choked over clouds of charred human flesh. Eric Foner, the pre-eminent historian of Reconstruction, calls the Colfax massacre “the bloodiest single instance of racial carnage in the Reconstruction era”; his magisterial study The Second Founding concludes that one key, blood-soaked lesson of the carnage was its demonstration of “the lengths to which some opponents of Reconstruction would go to regain their accustomed authority.”

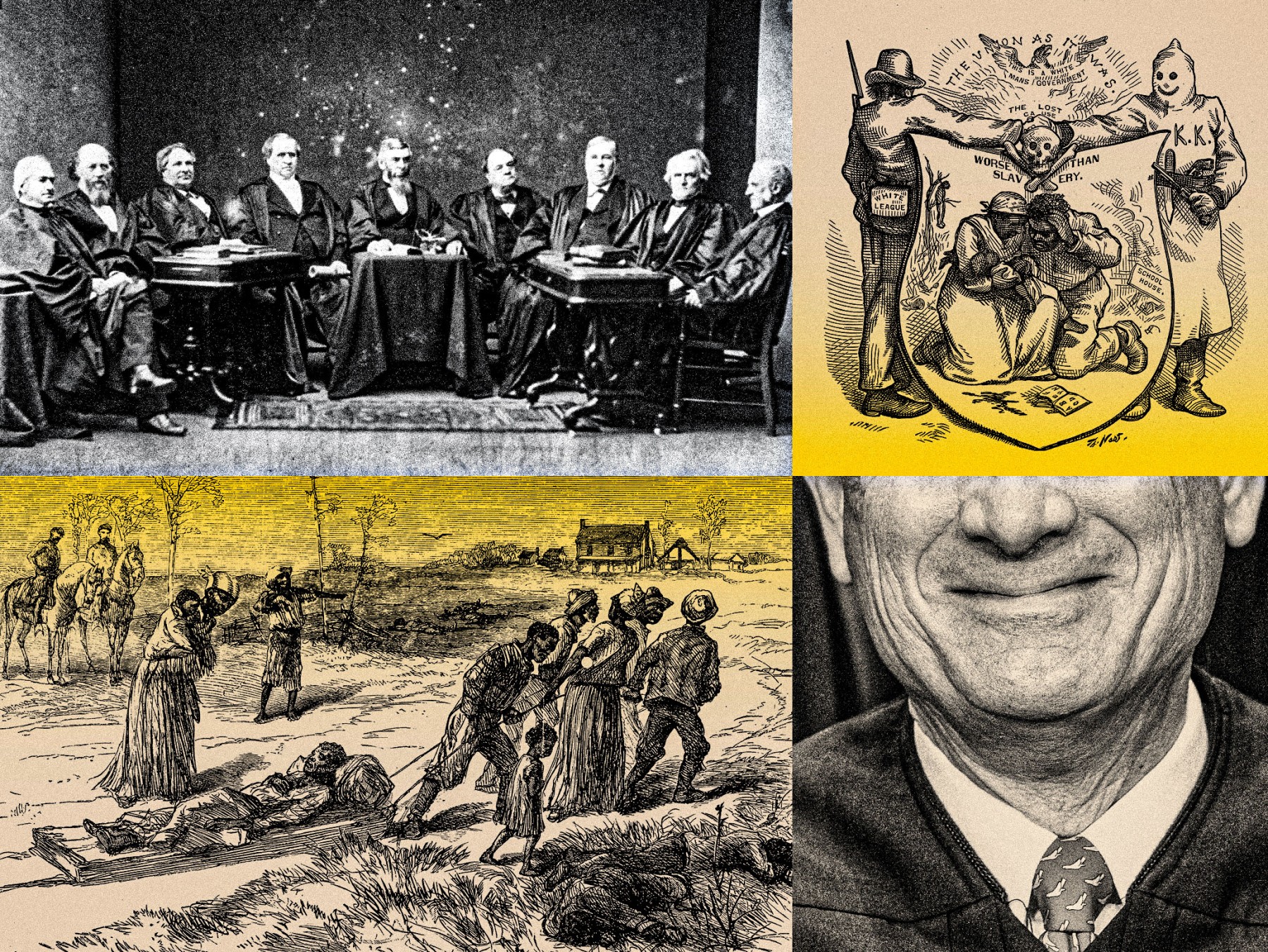

Reconstruction’s enemies had other powerful and robed allies on the U.S. Supreme Court. As Paul imagined that Easter morning before his mob lit the courthouse ablaze, 98 vigilantes were prosecuted for the Colfax massacre. A courageous U.S. attorney in New Orleans, James Beckwith, charged them under the Enforcement Act of 1870. Congress passed the Enforcement Act for this very purpose—in order to defend the constitutional rights of Black citizens awarded by the Reconstruction amendments against violence and intimidation in those states where freed Black citizens risked their lives to exercise these new rights. As a federal statute, the Enforcement Act was intended to provide these core protections regardless of whether the threats came from state and local officials, untrustworthy courts, or terror inflicted by an unchecked Klan.

Some 100 witnesses testified in the first trial, which ended in a hung jury; that proceeding was followed by a second trial that convicted just three men. Then, in 1876, in United States v. Cruikshank, the U.S. Supreme Court not only allowed those three murderers to go free, but also drove a stake into the heart of the Reconstruction dream. The Court declared the Enforcement Act all but unconstitutional, arguing that while the Reconstruction amendments empowered the federal government to intervene if states violated constitutional rights, they could not act against racist violence by individuals or institutions in a state. The decision closed its eyes to racial hatred, and included a plainly delusive disclaimer asserting that “We may suspect that race was the cause of the hostility, but it is not so averred.” As though to drive the point home, the Cruikshank decision stripped the federal government of the power to protect the constitutional rights of Blacks with federal troops, unless state legislatures specifically requested that assistance—an outcome that would occur precisely nowhere in the former Confederacy.

The Cruikshank court lacked intellectual heavyweights—but even the justices in the 5-4 majority certainly understood that the true consequence of this decision would be to green-light decades of Klan and White League terror across the south and southwest. In furnishing that fateful cover of legal impunity furnished to the forces of white supremacy alone, the majority in Cruikshank doomed efforts under the provisions of Reconstruction to register and protect Black voters.

But that was just the beginning. The Supreme Court’s steady erosion of the Reconstruction amendments—together with its evisceration of congressional efforts such as the Enforcement and Civil Rights acts—smothered the civil rights movement in the former slave South. The high court also permitted state constitutions to effectively wipe out Black voting rights, launched decades of Jim Crow suppression of the vote and nullified any hope of civic and socioeconomic equality. The upshot of all this regressive and cruel lawmaking from the bench was to erect a regime of injustice and inhumanity nearly as repugnant as slavery itself.

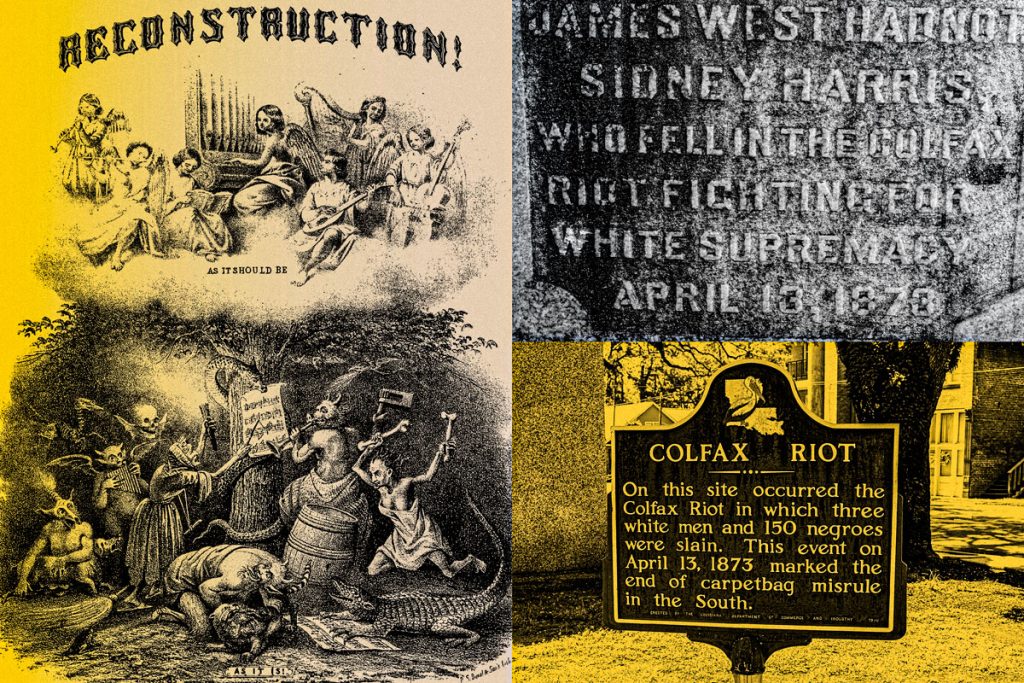

Americans’ awareness of the Reconstruction era is so impoverished that until last year, the historical marker in Colfax could proclaim it the scene of a Black riot that “marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.”

After the disputed election of 1876—in which the Democrats, then the party of white men, used violence and threats of violence to carry southern states where Black Americans were in the majority—federal troops vanished from the South almost entirely. Reconstruction was dead. Black voting would dwindle to almost nothing across much of the South for nearly 100 years. In the wake of Colfax, brutal and deadly white supremacist riots in menaced peaceful Black citizens in Charleston, Tulsa and Wilmington, among many other places. Decades of Jim Crow apartheid rule followed.

Americans’ awareness of the Reconstruction era is so impoverished that until last year, the historical marker in Colfax could proclaim it the scene of a Black riot that “marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.” In the annals of our legal history, meanwhile, Cruikshank, despite the predictable horrors it unleashed, rarely sits alongside Dred Scott, Korematsu, Lochner, and Plessy v. Ferguson on lists of the Supreme Court’s most shameful decisions. Nevertheless, Cruikshank’s parallels to our contemporary era of white minority rule—itself licensed and accelerated by a Roberts Supreme Court that sides with modern revanchist forces better mannered but no less determined than their nineteenth-century forebears—are impossible to miss.

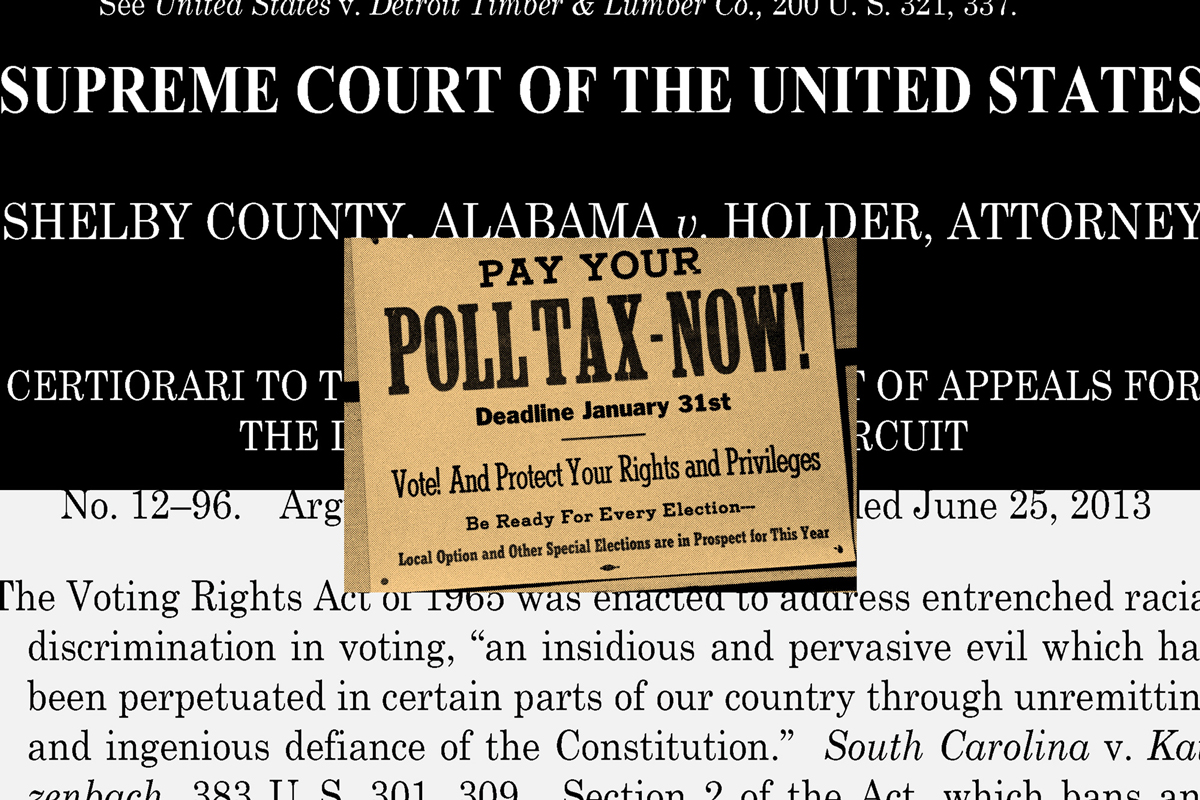

The Roberts Court’s rulings have sealed this reputation in a series of democracy and personal freedom cases. In 2010 came the disastrous ruling in Citizens United v. FEC, which unleashed unlimited dark money into our electoral system. Three years later, the court issued Shelby County v. Holder, which gutted preclearance protections from the Voting Rights Act, and set in motion the dizzying array of state-endorsed ballot-suppression measures that have rendered the simple act of voting an onerous, out-of-reach ordeal for all too many Americans—particularly if they happen not to be white. In the 2018 Abbott v. Perez decision, the Roberts court’s regressive majority reinforced the dismal logic of Shelby, permitting a racial gerrymander to stand on the presumption that it was adopted “in good faith” by GOP lawmakers in Texas, a state rife with Republican-engineered voter suppression. In the 2019 ruling Rucho v. Common Cause, the court further sanctioned extreme partisan gerrymanders and closed the federal courts to litigation protesting them. The 2021 ruling in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee went still further in the systematic dismantling of the Voting Rights Act by rolling back virtually all substantive provisions of its second section forbidding discrimination on the basis of race or language. This summer’s calamitous decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization marked the high court’s first formal repeal of a previously upheld civil right—the right to reproductive freedom vindicated in the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision—and thus stands as an ugly new chapter in the consolidation of an anti-Black, anti-civil rights regime that many, including the president of the United States, have called Jim Crow 2.0.

Neither the Roberts court nor the Reconstruction-era court was blind to the democratic decay and inequality that its disastrous decisions unleashed. Both courts, in the 1870s and the 2010s, were eager to declare victory over racism and end new federal protections of the vote in the name of a color-blind society only they could see. In this benighted parody of actual historically informed moral reasoning, one simply had no need to safeguard anyone’s rights in an allegedly harmonious and color-blind social order.

The parallels continue. Justices on both courts viewed protecting the right to vote as a racial entitlement that gave undue preference to Black citizens. Both courts disingenuously encouraged citizens to win change in state legislatures and sent them back unprotected to engage with an electoral process that the same courts debased and rigged to benefit the white supremacist status quo. And the consequences of both courts’ decisions were visible immediately—yet neither one backed down or changed course. It’s almost as if these were the outcomes they desired.

Taken together, the Reconstruction Court’s disgraceful and obviously disastrous decisions licensed violence against Blacks and created decades of white minority rule. It did not require a crystal ball to understand that southern state legislatures, given an end-around the federal Constitution, would take it, no matter how deadly or vicious the results might be. Cruikshank abandoned Black citizens to the Klan, and the Reconstruction-era civil-rights cases green-lit new state constitutions across the South that enshrined white supremacy and overrode the Reconstruction Amendments with poll taxes, literacy tests, and other barriers to the ballot box. With Court-sanctioned threats and intimidation keeping Black voters from the polls, Louisiana’s white legislature—in a Black majority state—passed a new court-sanctioned constitution in 1898 that made it so difficult for Blacks to vote that the number of registered Blacks dropped immediately from 130,000 in 1897 to fewer than 5,000 by 1900.

Likewise, the Roberts Court’s treatment of democracy, leaving it to states where the largest growth industry seems to be manufacturing new “race-neutral” laws that still keep Black and Latino voters from the ballot box, uses the vague doctrines of federalism as a cover for the new Jim Crow. In his 2013 opinion in Shelby, Roberts created an entirely new and extra-constitutional doctrine of “equal sovereignty” among the states as he ended the practice of “preclearance” under the Voting Rights Act—the process by which those states with the worst history of racial prejudice in voting laws had to win federal approval before making any changes to election policies and procedures. Roberts cherry-picked his data points, noted the nation had elected its first Black president, and with barely any pretense to consult historical and next-generation patterns of voter suppression, insisted that “things have changed dramatically” in the South.

It would be difficult to imagine a more obviously disastrous misreading of America, the South, or the state of our nation. Roberts was proven wrong that very afternoon, when Texas enacted a Voter ID bill that preclearance had previously blocked. It required forms of identification that the state knew some 600,000 Latino voters lacked. It allowed hunters and militiamen to vote with their gun licenses—but prevented students from voting with a college ID. Similar voting laws that disproportionately affected Black and Latino voters followed in short order in Georgia, Florida, North Carolina, Mississippi, and Tennessee.

Things had changed in the South? Dramatically? That claim only passes the laugh test if one assumes that by “changed,” Roberts meant they reverted to the way they’d always been. The South post-Shelby freed the old forces of racial animus set loose by Cruikshank and the Reconstruction civil rights cases and tamed only by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The only salient difference was that this time, Jim Crow possessed a nice suit, sophisticated computers and an advanced degree in partisan mapmaking and data science. Perhaps he had a law degree from a fancy college and sported a far more respectable black robe behind a bench. But his job—disenfranchising voters and enforcing white minority rule—remained the same.

Such is the gruesome face of legal power in today’s America. But if you want to understand the true deviousness of the hard right strategy to rule under near-permanent conditions of minority rule and judicial supremacy, you have to approach these cases as the conservatives and the Federalist Society have: together, as part of a focused, long-term effort to stack the courts and weaponize the counter-majoritarian structures of our system to entrench themselves in power, no matter how few their numbers, no matter the election results. The multi-racial coalition that elected the nation’s first Black president in 2008 terrified the GOP; many of its most savvy strategists recognized it could be a minority party for a generation. They also recognized that while the Obama election might have been historic, the midterms, in a census year, could be much more consequential. In 2010, the Citizens United decision loosed unlimited dark money from shadowy donors; Republicans routed $30 million—peanuts now, but a giant investment down ballot at the time—into a strategy called REDMAP, short for the Redistricting Majority Project. The strategy went all in on down-ballot races, funding otherwise ignored state legislative contests in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, Florida, North Carolina and many other states. Democrats overlooked this mobilization entirely and have not held power in those state legislatures since. The following year, the GOP gerrymandered themselves maps that produced Republican majorities for the entire decade—maps that withstood massive blue waves, maps on which they could not, and did not, lose.

The Shelby decision freed politicians to once again pass laws designed to prevent the voters they didn’t want at the polls from casting a ballot; in their more ambitious guises, these new Jim Crow laws required voters to leap hurdles while running a marathon simply to make their voices heard. Across the South, and across the purple states dyed an indelible REDMAP red in the wake of the 2010 midterms, next-generation suppression efforts proliferated and multiplied. It was a competition between Big 10 and SEC states that previously saved warfare for Saturday football games in the fall: Voter ID bills, precinct closures, voter roll purges, new limitations on early and absentee voting, stringent new registration requirements aimed at students, and punitive measures tailored to enable criminal prosecutions of nonprofits conducting voter registration drives.

Both the Reconstruction and the Roberts courts, in the 1870s and the 2010s, were eager to declare victory over racism and end new federal protections of the vote in the name of a color-blind society only they could see.

In 2016, Donald Trump lost the popular vote but carried the Electoral College by fewer than 45,000 votes in three states deeply gerrymandered in the wake of REDMAP—which all made voting more difficult between 2010 and 2016. Trump’s three Supreme Court appointments pushed the number of justices selected by presidents who lost the popular vote from two conservatives all the way to a majority of five.

Each of the Roberts court’s landmark rulings on voting rights and civil rights has thrust the idea of free and fair elections a little deeper underwater as it circles the drain. After Shelby, Arizona, which has an ugly century-long history of suppression efforts, quickly passed laws that had been blocked under preclearance. Among its most effective new vote-suppressing measures was a ban on third-party ballot collection and new penalties for out-of-precinct voting. The state enacted both laws, despite overwhelming evidence that they disproportionately targeted and burdened minority voters who live in communities where mail service is unreliable—or who had their precincts moved so often by the state that the search for a legal balloting station creates tremendous confusion and exasperation. Less partisan courts put an end to these laws.

But the Roberts Court was undeterred. In its majority opinion in Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, written by hard-right Associate Justice Alito, the court determined that anything a legislature did in the name of fighting voter fraud must be given the benefit of the doubt. (Reader, there was no voter fraud—neither in the case under review in Brnovich, nor in the hundreds of cases of alleged Democratic voter fraud relentlessly publicized by the minoritarian hard right.) So to return to the big picture: eviscerating the Voting Rights Act’s section five—the preclearance provision struck down in Shelby—led to new laws that then allowed the Court to gut the antidiscrimnation provisions of the Voting Rights Act’s section two. The immediate practical upshot of that decision was to make it harder for minorities to vote in a state where the 2020 presidential election was decided by fewer than 10,500 votes. Rinse and repeat in Georgia, where fewer than 11,800 votes made the difference. In short: election of 1876, meet election of 2024.

Some federal courts have resisted at least part of the new wave of vote-suppression putsches in state legislatures. They declared gerrymandered maps unconstitutional in Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, North Carolina and Maryland, and ordered them redrawn to reflect the will of the people. Yet here again, Roberts and his wrecking crew sprang into action—countermanding the judgements of more than a dozen federal judges, appointed by presidents of both parties. All these presiding justices recognized the urgency of securing genuine ballot access in a democracy, and believed federal courts had the neutral tools necessary to identify when a gerrymander broke faith with free and fair elections.

These lower court judges observed lawmakers locking themselves into virtually unchallenged and unending power with ultra-sophisticated technology and recognized the judiciary needed to step in because no one else could. But in 2019’s Rucho v. Common Cause, Roberts shrugged, pointed to a gerrymander that voters somehow managed to unwind 40 years ago in Pennsylvania, and insisted the courts couldn’t possibly pick political winners and losers. The ruling, of course, locked in his party as the winners in nearly all of those states, securing a second decade of minority rule in otherwise competitive states, while making it impossible to challenge similar rigged maps in Texas, Georgia, Florida and so many other states. Rucho v. Common Cause is the authority presiding over the rolling bacchanalia of greedy gerrymanders passed nationwide this year. (It is worth noting here that Roberts himself launched his legal career as a Reagan-era Justice Department lawyer specializing in voting-rights challenges accruing to the maximum benefit of Republican mobilizations of electoral power; it’s also worth recalling that, together with his colleagues Neil Gorsuch and Amy Coney Barrett, he was part of the Bush-Cheney legal team dispatched to Florida in the deadlocked presidential election of 2000 to deliver the presidency to the GOP in the flagrantly antidemocratic Supreme Court ruling in Bush v. Gore.)

The combination of Shelby plus Rucho plus Abbott v. Perez has empowered GOP lawmakers to adopt an extreme partisan and racial gerrymander of both state legislatures and the congressional delegations—all without preclearance by the government, and without any recourse for citizens seeking remedies to electoral abuses in the federal courts. Yet more absurdly, this trifecta of anti-voting-rights decisions essentially mandate a presumption of good faith in reviewing the efforts of lawmakers to rig district maps throughout the country so as to reduce Black and Latino political power. In Texas alone, these efforts have created nearly two-thirds white-majority seats in a state where white voters are approximately 40 percent of the population.

From their gerrymandered fiefdoms, state legislatures in Texas, Oklahoma, Ohio and a dozen other states have moved to end abortion access in the days after Dobbs, either via new legislation or the enforcement of previous anti-abortion laws from the pre-Roe era. There is nothing that voters can do about this.

This brings us to the big lie in Dobbs—that the high court was deferring to democratic deliberation in the states over against the dangerous judicial social engineering enshrined in Roe. Justice Alito’s decision, which actually drew from English law of the 1250s, wasn’t just medieval cosplay. Alito modestly proclaimed that by overturning Roe, the Court simply returned a contentious issue to the democratic process. “We thus return the power to weigh those arguments to the people and their elected representatives,” he proclaimed, noting that “women are not without electoral or political power” and insisting “we do not pretend to know how our political system or society will respond.”

Such eager blame-shifting is nothing more than trolling from the bench. One is tempted to respond in kind and suggest that Alito put down his thirteenth-century law books and engage with the way that partisan gerrymandering has severed the connection between the people and their elected representatives in swing states such as Wisconsin, Ohio, North Carolina, Florida, and Georgia. He might then consider how Republican vote-rigging has built firewalls against changing demographics in Texas and Arizona, and pushed policy further right than voters’ actual positions indicate in one-party states such as Oklahoma and Alabama.

Alito’s disingenuous reasoning in Dobbs is designed to ignore all this. He isn’t about to endorse any reapportionment of political power that would return these arguments to the people and their elected representatives. No, he’s returning them to gerrymandered legislatures in states where the majority cannot change their government even when they win hundreds of thousands more votes.

And this, in turn, is possible because the U.S. Supreme Court has also shuttered the federal courts to partisan gerrymandering claims, ruling that gerrymandering was a nonjusticiable political issue–one that (yes) is best left to the people’s elected representatives to decide. Alito might bask in the abstract proposition that he’s returning abortion rights to the people—but in reality, he’s returning them to a political system he has already helped rig in order to create the anti-majoritarian policy preferences he then enshrines in constitutional jurisprudence. Medieval law, indeed.

You might begin to sense a theme here. The court subverts majority rule and tilts the playing field to favor a partisan team and its body of pre-existing political-cum-ruling agendas. The court then upends long-held constitutional rights and hands them back to states where they’ve made it so majorities have no influence. The justices in the court’s right-wing majority then innocently proclaim that they have no idea what will happen next—even as the states they have rigged for permanent minority rule rush to pass laws most people in those states disagree with in anticipation of the high court’s decision. Then the justices applaud themselves for enhancing democracy when in fact they have gutted it and reduced majoritarianism to the wishes and whims of ideologues without any semblance of accountability to the people—and a life-time appointment to boot.

In championing their minoritarian agenda, today’s conservative justices even sound like their nineteenth-century forebears.

And in many ways, the high court’s new hard-right supermajority is just getting started. This fall, the Supreme Court will hear a case from North Carolina called Moore v. Harper, which involves a crackpot theory known as the Independent State Legislative Doctrine. This is phony originalist nonsense that suggests state legislatures should have unfettered control over all election laws and procedures—free from pesky vetoes by governors or supervision by state constitutions and state supreme courts—because the word “legislature” appears in the U.S. Constitution. This doctrine pointedly ignores that the same document, for example, also contains the Elections Clause, which states clearly that “Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such regulations”—let alone the decades of precedent that has established that “legislature” in the Constitution’s usage actually means the legislative process.

The case involves North Carolina’s gerrymandered congressional map, and you won’t be surprised to see how it fits into the big picture of the Court dismantling every single ground-up provision that has helped bolster the ever embattled project of achieving truly representative democracy in this country. Roberts’s decision in Rucho, which closed the federal courts to gerrymandering claims, emphasized that state courts were the proper venue for all such challenges, blithely asserting that state constitutions provided ample protections of the right to vote. So citizens protesting rigged maps duly took their claims to the state supreme courts, which cited state constitutions in overturning the maps. Another regressive Roberts court ruling in Moore v. Harper would now close even that avenue of unreliable redress. Four justices have already signaled their support. It will only take just one more to hand gerrymandered legislatures unprecedented and unlimited control over how federal elections are conducted.

The Dobbs decision, along with the egregiously partisan decisions in the Roberts court’s voting rights cases, has badly damaged the Court’s credibility among the public. Large polled majorities now view the justices not as arbiters of neutral wisdom but the most reliable and unaccountable of partisan hacks. This much, at least, is progress. But it is only the beginning of what must be an entirely changed understanding of the high court.

Progressive faith in the Court is largely based on that small 1950s and ’60s window when the Warren Court expanded rights and stood for political equality. This largely unearned and romanticized view of the high court as an ally to multiracial democracy has obscured its much longer, far less democratic, racially regressive and oligarchy-enabling actual history. In championing their minoritarian agenda, today’s conservative justices even sound like their nineteenth-century forebears. During oral arguments in the Shelby case, Associate Justice Antonin Scalia bemoaned “the perpetuation of racial entitlements. Once you enact them,” he said, “it’s very hard to get out.” During Cruikshank, the high court’s justices also fretted that the 15th Amendment created a racial entitlement; Scalia’s concerns echoed those of Justice Nathan Clifford, who responded to the government’s case with angered disbelief. “Then colored men have more rights in the United States courts than white men!” Clifford said. Cruikshank’s own lawyers, meanwhile, told the court that “The shackles will have fallen in vain from four millions of blacks, who were born slaves, if fetters more falling are to be riveted on so many millions of whites, who were born free.”

Later in those arguments, the attorney suggested that any Black man deprived of his right to vote could seek restitution in state court: “If eight hundred thousand voters cannot secure the rights to which they had been declared entitled, then that is the best argument that they are not worthy of them.” As Lane writes in his epic history, “No one on the Court disputed the point.” It is, of course, nearly as straight a line from Cruikshank to decades of Jim Crow, as it is a well-trod path from there through the reasoning in Shelby, in Rucho and then in Dobbs. Fix it electorally, says a court that knows all too well no such thing is possible, in part because of its own rulings.

Three white men died in Colfax that bloody spring weekend of 1873. Many years later, white townsfolk erected an obelisk in their honor. “In loving remembrance,” it began, “erected to the memory of the heroes Stephen Decatur Parish, James West Hadnot, Sidney Harris, who fell in the Colfax riot fighting for white supremacy.” It’s as honest a monument as you’re ever likely to find. One can readily imagine future generations of belligerently entitled white nationalists in America erecting a similar one to today’s U.S. Supreme Court.

David Daley is the author of Ratf**ked: Why Your Vote Doesn't Count and Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy.