The Federal Reserve announced last week that it would be raising interest rates again—this time by 75 basis points, or three-quarters of a percentage point. This high-profile move was the Fed’s latest bid to curb rampant inflation, which now rests at 9.1 percent. With this increase, benchmark interest rates are currently between 2.25-2.5%, the highest they’ve been since 2019, before the Fed decided to flood the economy with cheap money to keep the U.S. economy afloat during the Covid-19 crisis and the ensuing economic downturn.

Under the guise of a generalized war on inflation, however, the Fed has adopted a monetary strategy that’s explicitly antagonistic toward the needs of poor and working-class people, a disproportionate number of whom are people of color. The reasoning here is as blunt as it is destructive: Fed Chair Jerome Powell has himself admitted that nothing in the successive rate hikes will directly address the spiraling costs energy, food, or housing—i.e., the productive sectors now experiencing the most acute inflation, and the spheres in which working Americans suffer its worst effects. While energy prices are showing signs of falling, there are no such signs for food or housing prices.

What’s more, the Fed is using interest rates to “cool” the economy by making investment more costly, a policy course that risks continuing economic contraction, and even triggering a recession. Powell continues to insist that this is not the Fed’s intent, and that a recession is not inevitable. But the fact remains that a “cooling” of the economy is a downturn by any other name—and, as a key component in the Fed’s obsessive pursuit of interest rate hikes, it is likely to harm the very people who currently benefit from a tight labor market: working-class Americans.

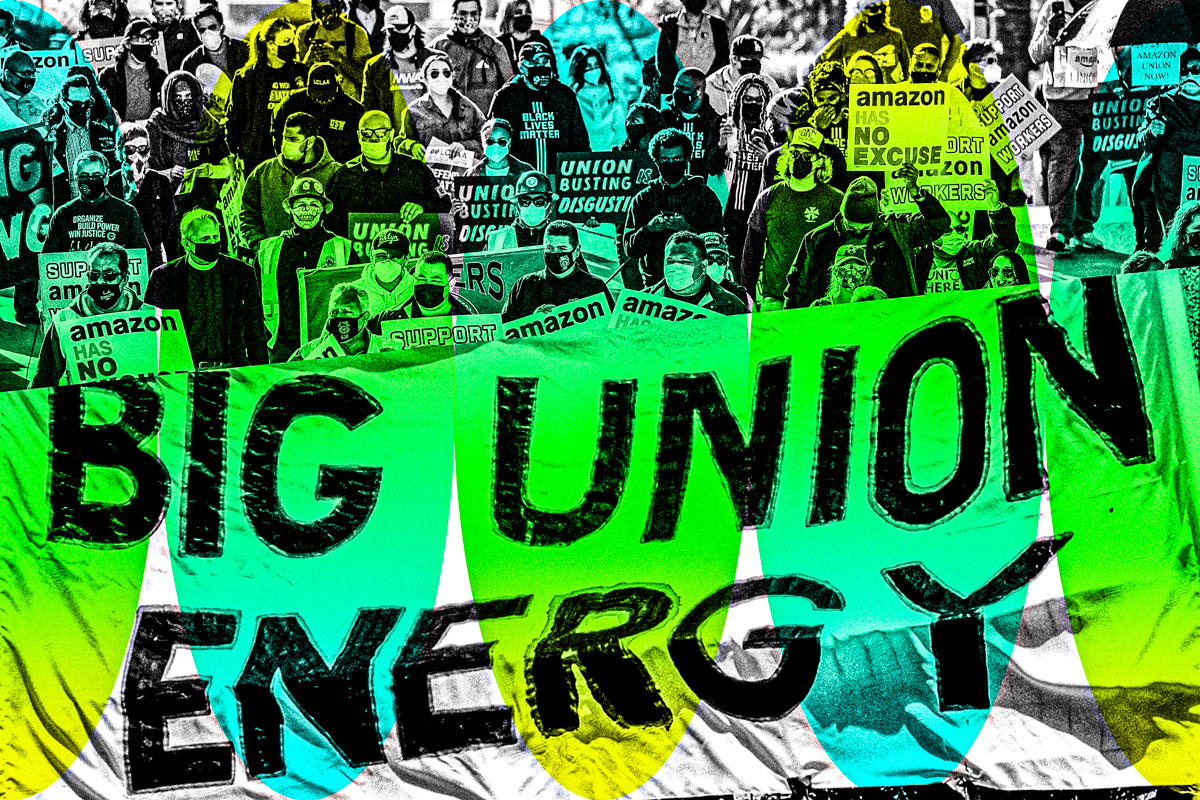

This is far from an abstract point in debates over monetary policy, for the very moment at which the Fed is moving to tamp down wages and slower growth in the anti-inflation cause, American workers have embarked on a historic run of labor organizing. And the broad economic conditions stoking this surge of unionized workplaces have to do with the increased control workers have over tight labor markets.

One apparent key ingredient of the present union surge is something we’ve rarely encountered in the U.S. political economy: wage growth.

Tight labor markets shift bargaining power to employees because the overall labor economy has many more jobs going begging than there are workers willing to accept these jobs. The added pressures of a tight labor supply force employers to offer better wages and benefits in order to compete for employees. Add to these structural shifts a generational pandemic with yet-to-be-determined long-term health effects, and it becomes clear that workers are especially unwilling to accept terms of employment that they find inadequate.

These trends are what’s behind the wave of new organizing now in the once-moribund American labor movement. According to recent data from the National Labor Review Board (NLRB), more union petitions were filed during the first nine months of Fiscal Year 2022 (October 2021-June 2022) than in all of 2021 combined.

This is a crucial step forward for American workers, since unionization has long been the primary vehicle for them to improve their living standards. Employers, too, are acutely aware of the potent impact of unionizing and have long enlisted the long arm of the state to suppress demands for greater workplace power and representation on the part of workers.

Another apparent key ingredient of the present union surge is something we’ve rarely encountered in the U.S. political economy: wage growth. Over the past fifty years, wage growth in the United States has stagnated even though, over the same period, productivity—or per capita economic output—has steadily increased. What this means for the real economy is that while the capitalist returns on investment have grown, workers have received a dwindling share of that growth—a principal driver of explosive inequality in American life.

And this structural inequality is, in turn, a direct outgrowth of business’s seventy-year war on organized labor. Since peaking at just shy of 35 percent in 1954, union membership in the United States has been steadily declining. This was no accident. As linguist and political activist Noam Chomsky reminds us, business elites are constantly fighting a vicious class war against working people. Since cheap labor costs are a sure-fire way of securing greater profits, businesses have a vested interest in paying workers as little as possible, while also ensuring that workers have no defense against their exploitation. It should come as no surprise, then, that major corporations like Amazon and Starbucks—ground-zero for the current labor movement—have run sustained campaigns on behalf of their shareholders to undermine unionization.

Amazon is, you might say, a prime offender. Since the Amazon Labor Union (ALU) formally chartered itself on April 1, the mega-corporation has poured vast resources into a union-busting initiative seeking to dissuade its enormous, viciously exploited workforce from joining the union.

Amazon’s Pacific Northwest neighbor Starbucks is working from the same playbook as it pursues its own anti-union agenda, via punitive measures such as withholding new benefits from workers at unionized stores. Consistent with the long history of anti-union crackdowns, Amazon, Starbucks, and other marquee employers in the retail and service economies want to maintain an unorganized, disempowered, and—most important—underpaid labor pool.

This broad anti-labor agenda chimes in unison with the recent Fed policy aimed at reducing wages while leaving many cost-of-living increases essentially untouched by monetary policy. Never mind that wage growth is now well outpaced by inflation. As Fed chair Powell has repeatedly stressed, the Fed believes that wage growth must be slowed if inflation is to be brought to heel.

The Fed is on course to undermine workers’ demands for better pay, benefits, and a more democratic workplace.

Though the Fed has sent mixed signals about whether it is trying to trigger a recession, it has all-too clearly indicated that for inflation to be tamed, interest rate hikes have to loosen the tight labor market. In other words, supply and demand within the labor market, in the Fed’s view, must be brought “closer together.” And since workers now enjoy more power than they have attained for decades, the Fed is on course to undermine workers’ demands for better pay, benefits, and a more democratic workplace.

If the Fed’s hawkish inflation stance reduces overall growth, workers’ renewed bargaining strength will likely begin to erode. But as the old industrial labor movement recognized, there is both strength in numbers and power in a union. That’s why it’s been heartening to see major organizing drives continue apace amid the Fed’s successive interventions to “cool down” the labor economy. Just last month, employees at two Chipotle restaurants—one in Maine and one in Michigan—filed a petition with the NLRB to schedule a union vote. Workers at a Washington, D.C. Lululemon store decided to do the same. And in late July, employees at a Trader Joe’s in Hadley, Mass., voted to unionize, with Trader Joe’s workers in Minnesota and Colorado looking to do the same. If the union gains at retail giant Starbucks are any indication—clocking successful organizing drives at more than 200 stores in fairly rapid order—these efforts can take off at warp speed once the wheels are in motion.

This burgeoning wave of organizing in the U.S. labor movement should excite anyone committed to justice, especially given that much of it has taken place in the so-called service industry. This sector typically offers low-paid work with limited benefits and other workplace protections—and not surprisingly, it’s also a lead sector in which people of color and women are disproportionately employed.

Still, the road ahead will not be easy. For all the proven efficacy of unions as an engine of trans-sectoral bargaining strength and wage-and-benefit gains, the modern American labor movement was also riven with internal strife and division, particularly in the quest for racial justice in the workplace and beyond. Contemporary organizers are aware of these historic shortcomings, and have developed innovative and inclusive news organizing campaign to build interracial solidarity.

In addition, today’s new cohort of labor organizing faces key structural challenges, such as workplace retention. Many workers often view service work as temporary rather than a long-term career, often because of poor pay and benefits. As a result, service employees might not consider a struggle against powerful, monied interests to be worth it in the end. Still, especially amid the emerging Fed-orchestrated campaign to create employer-friendly conditions of economic contraction, it’s imperative that organized labor stands firm—and keeps expanding.

Jared Clemons received his Ph.D. in political science from Duke University, where he studied race and political economy. He is a postdoctoral research fellow at Princeton University’s Center for the Study of Democratic Politics.