I was talking with a former Black Panther, who, after a lifetime of struggle and resistance, remains militant. In our state, many Black children attend mostly white schools where, according to lawmakers, discussing anything resembling critical race theory—or much of racial history, for that matter—is illegal.

Diary of a Targeted Teacher

She had an idea on how to solve this.

“Segregate our schools,” she said. “Let Black families and Black teachers teach Black children and let whites deal with whites.”

Bans on teaching racial theory and history are layered with harm; not only did white America institute the very prison and prism of racism, it now also outlaws the discussion on where to find keys to freedom. And, in the worst of cuts, it does so under the guise of protecting white children.

“I don’t want my child to feel bad about being white,” parents say. “I don’t want them to feel shame or guilt about something they didn’t do.”

No parent does. Yet such statements—however emotionally honest—reveal a complete misunderstanding of race and racial theory while also admitting a most painful one-sided partiality: we only want to protect the feelings of our white children.

But what of the feelings of Black and brown children? Are they not worthy of protection, too?

The outlawing of racial instruction ostracizes children of color by heightening and emphasizing race as their problem, not ours, as if to say: if only you weren’t Black, then we wouldn’t have any problems. My friend’s suggestion? Let us care for our own. Our children are being harmed by attending schools like this. Whiteness is making things worse.

In my classes, we do, in fact, discuss, examine and question race and American racism. Yet many days, I am left wondering: who benefits?

Who are such classes and discussions designed to help? White students? Black Students? Brown students?

The outlawing of racial instruction ostracizes children of color by heightening and emphasizing race as their problem, as if to say: if only you weren’t Black, then we wouldn’t have any problems.

Is it possible to create a racial curriculum where all students benefit? I once said yes. Now, I’m no longer sure.

Certainly, Black students benefit in classrooms that make visible what is invisible. When we bring into the light what was kept in the shadows, there is an alignment. Telling the truth is integral to the process by which we become free. If we can create places where students of color may speak openly—in safety, community and understanding—about their experiences, then there is a lightening, an alleviation of the burden of suffering that comes in so many forms, large and small.

“At least we’re talking about things,” one Black student said. “In so many places, people aren’t even talking.”

White students, too, can benefit from this. To borrow a phrase from the Gospels: as the scales fall from our eyes, and we begin to see the world in ways previously unseen. And our own lives may shift as we begin to realize freedom from our own racial conditioning, moving toward relationship and allyship, not ignorance. Our lives become less harmful. Color is no longer something we’re oblivious to, and this awakening happens by encountering stories and experiences unlike our own. For us to hear what has previously gone unheard challenges us, and calls us into self-reflection and rectifying action aimed at justice.

“Being Black in America means that as everyone else takes one step, I must take three,” one Black student tells her classmates. “Being Black is about preservation in a country where you were once hated and, even today, may still be hated.”

Yet what happens when there is no hearing? When things are offered, yet not received?

“Can we talk with you after class?” one Black student asks.

He and three others stay behind after everyone else leaves. They are unsettled.

“Things aren’t working,” they say. “This isn’t working.”

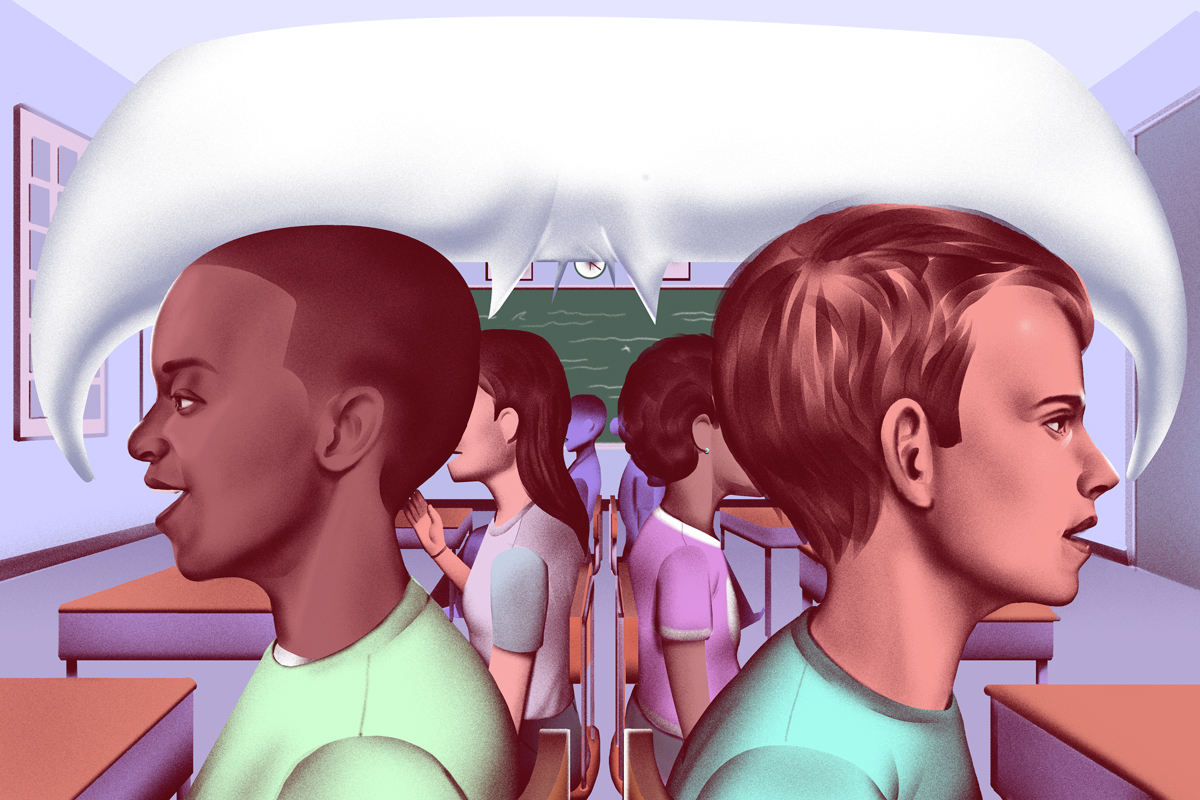

They describe a frustration, a rejection of sorts. Each day in class, they wade bravely into the waters, opening up, describing experiences and pain, from white teachers brazenly touching their hair, to cops pulling their fathers over for no good reason, to hearing the N-word on a routine basis. They want white classmates to see, to roar in rage, to weep, to . . . do something.

“They just sit there,” one student says. “Why do they just sit there?”

Let me be clear: many white students don’t just sit there. They experience an awakening of sorts, and their hearts and minds respond with an urgent energy as a critical feedback loop begins: Black students, heartened by such a response, open up more, while white students, both angry and responsive, lean toward the pain instead of away from it.

Yet this is not always the case. Some white students seem trapped in a type of paralysis. These Black students who hung around after class? They are suffering from yet another form of broken-heartedness, a low point reflecting yet another blow dealt to the illusion of substantive progress toward inter-racial understanding. As we continue talking, it becomes clear to me that these Black students once walked into class seeing it as a panacea, and now no longer do.

I call this the Myth of Difficult Conversations. It’s pedagogically fashionable these days, this notion of difficult conversations. Teachers are trained to foster and guide difficult conversations with students, which is certainly good educator training, but often feels like code for: how the hell do we teach when all around us nobody knows what to believe? As we try to talk honestly with one another, we’re also grappling with all sorts of baleful influences outside the room we’re talking in: conspiracy theories, devolving discourse, the Tower of Babel that is social media.

The pedagogical idea of the difficult conversation is to create space in a classroom where conflicting or differing viewpoints can be expressed, shared and understood safely. It is a noble ideal, both democratic and spiritual, one that’s often proffered as a medicinal tonic for our fracturing society.

I used to believe in the difficult conversation. Now?

Within a mixed racial space such as a school or classroom, Black safety and security are often yoked to the levels of white understanding. So it’s crucial to cultivate white consciousness as a baseline foundation of the difficult conversation—yet if we are starting from scratch, the effort to shore up white-based understandings of race can be quite harmful and difficult.

Again, I want to be fair and encouraging: so many white students respond with open hearts and brave minds, moving away from delusion and closer to the experiences of their Black and brown classmates.

Yet others can’t. Or won’t.

And even if every white student opens up to racial reality and pain, the process often creates a dynamic fraught with dysfunction and damage. If this is the first time many white students have ever seriously considered race, then their questions, comments and actions, however well intended, are still clumsy and ignorant. It’s not unlike a mixed classroom of readers, where some are AP scholars and others are barely literate. If so, the whole course of inquiry here can be triggering for Black and Brown students, who are then forced to endure the experience of being teachers, victims and survivors, all at the same time.

The whole course of inquiry here can be triggering for Black and Brown students, who are forced to endure the experience of being teachers, victims and survivors, all at the same time.

And for me as a teacher, it can be overwhelming and exhausting, the never-ending tightrope of trying to protect the sanctity of vulnerable Black voices in a white room while encouraging white hearts and minds to stay open, not shut down from shame, guilt or confusion.

I think of Reni Eddo-Lodge’s “Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race.”

I’m no longer engaging with white people on the topic of race. Not all white people, just the vast majority who refuse to accept the legitimacy of structural racism and its symptoms. I can no longer engage with the gulf of an emotional disconnect that white people display when a person of colour articulates our experiences. You can see their eyes shut down and harden. It’s like treacle is poured into their ears, blocking up their ear canals like they can no longer hear us. . . .

Even if they can hear you, they’re not really listening. It’s like something happens to the words as they leave my mouth and reach their ears. The words hit a barrier of denial and they don’t get any further. . . .

So I’m no longer talking to white people about race. I don’t have a huge amount of power to change the way the world works, but I can set boundaries. I can halt the entitlement they feel towards me and I’ll start that by stopping the conversation. The balance is too far swung in their favour. Their intent is often not to listen or learn, but to exert their power, to prove me wrong, to emotionally drain me, and to rebalance the status quo. I’m not talking to white people about race unless I absolutely have to. If there’s something like a media or conference appearance that means that someone might hear what I’m saying and feel less alone, then I’ll participate. But I’m no longer dealing with people who don’t want to hear it, wish to ridicule it and frankly, don’t deserve it.

As Anthony Conwright declared recently in The Forum, real racial work can be detoured by whites who center themselves—excuse me, ourselves—in the discussion, thus shifting real structural change from the front to the backseat. He calls it the “Trouble with White Fragility Discourse” and it was only a hop, skip, and jump for me to retitle it: “The Trouble with Classroom Discourse.” Conwright references Bayard Rustin:

In a talk before a gay student group at the University of Pennsylvania in 1986, civil rights leader Bayard Rustin said, “our job is not to get those people who dislike us to love us. Nor was our aim in the civil rights movement to get prejudiced white people to love us. Our aim was to try to create the kind of America, legislatively, morally, and psychologically, such that even though some whites continued to hate us, they could not openly manifest that hate.”

In my experience, it is through honest conversations that relationships are forged and understanding achieved. As a white man, I saw my own awakening hastened in such ways. Yet as a white educator attempting to teach race, am I committing the same transgressions Conwright and Rustin describe? Am I subtly sacrificing Black experiences in order to gain white awakening? Hoping more for good-feeling relationships than actual and structural change?

Again: who benefits?

I find myself lingering on the suggestion of my friend the former Panther: “Let Black families and Black teachers teach Black children, and let whites deal with whites.”

If Eddo-Lodge represents countless Black voices when she refuses to speak to white people about race, does the duty therefore not shift and fall upon my own shoulders? My own white shoulders?

And who is there in the room with me?

Willie Randall is the pseudonym for an American educator who’s taught race and racial theory at multiple schools in multiple states.