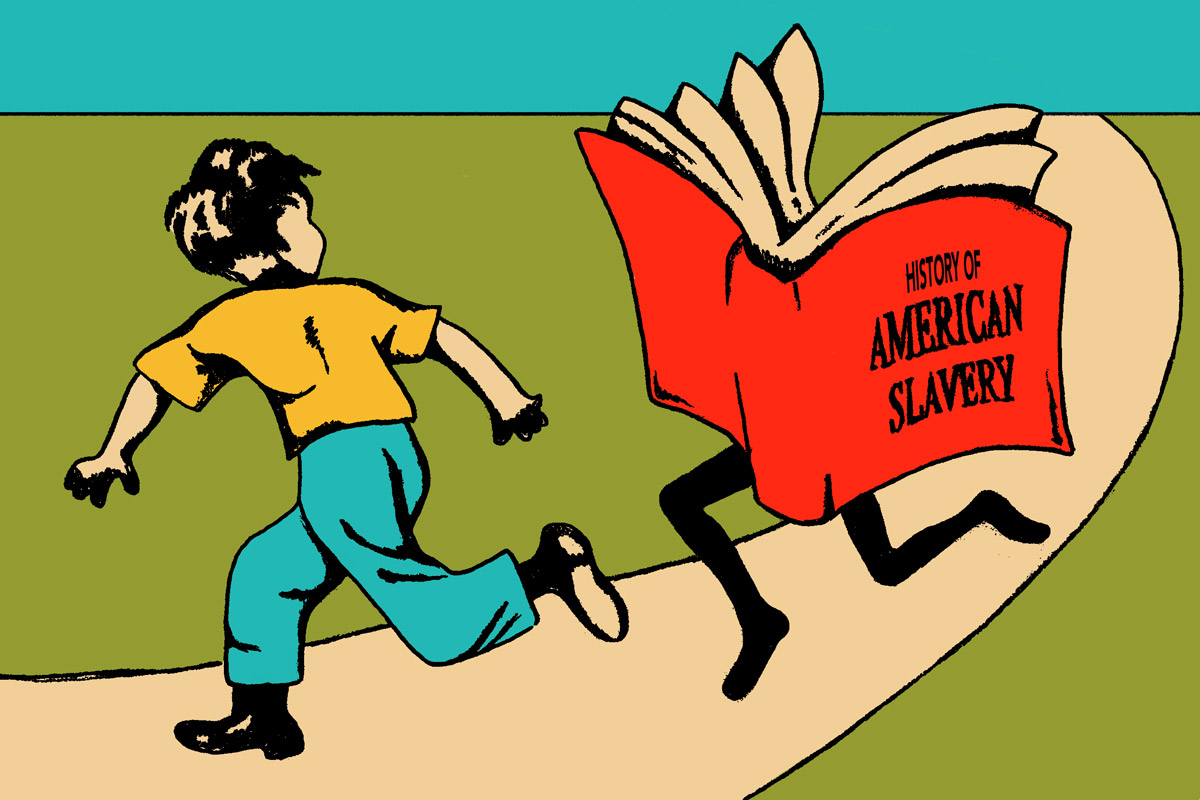

Reactionary panics about what children learn in school are about as old as time. And they won’t ever go away. So if you want to fight bans of LBGT books, Florida GOP Governor Ron DeSantis’s lunatic crusade against math texts supposedly pushing social-emotional learning, or panics about the teaching of America’s true history that somehow supposedly teach white children to “hate themselves,” you really have no choice. You have to put Twitter or the TV aside. You have to start at the very beginning.

For as long as there have been villages, there have been young people who chafed at their confines. They strike out for the wider world. Having seen something of elsewhere and its strange ways, rejecting some, embracing others, the prodigal returns, and perhaps evangelizes: Instead of hunting and/or gathering this way, why don’t we try it like that?

Think of the elder who responds with a frantic, paranoid horror as history’s first conservative. Comes the modern world, and the condition of the village prodigal becomes universal: everyone is bombarded by challenges to settled ways, unspooling remorselessly, year in and year out. Old hierarchies shift. Sometimes the changes are tectonic: African Americans, once chattel, become citizens; women, once defined socially as extensions of their fathers or husbands, become legal individuals; people who desire those of the same gender sexually, once seen only as devils in human form, become trusted neighbors and friends. This is what Martin Luther King Jr. was talking about when he said the moral arc of the universe is long, but bends toward justice—though sometimes these changes can feel, to those who experience them as dispossession, like they happen overnight.

The word for this flattening of hierarchies of authority is “liberalism.” And it drives those who didn’t find anything wrong with the old hierarchies of authority in the first place—whom history came to call “conservatives”—quite berserk. They are the kind of people, as the mission statement published in the first issue of National Review in 1955 put it, who seek to stand “athwart history, yelling Stop.”

Another defining feature of modernity is the emergence of a class of individuals who specialize in figuring out how the world works—scientists; and of the integration of the knowledge thus derived into new ways to experience, manipulate, and master the world—technology. Inexorably, science and technology spur changes in long-settled habits and understandings that made perfectly good sense when our knowledge of the world and our ability to manipulate it were very different. Take, for example, the notion that the sun revolves around the Earth. Or the taboo against having sex outside of marriage—for how else to ensure the care of the child that might ensue?

Schooling, done properly, is the opposite of conservatism. So is it any wonder it frequently drives conservatives berserk?

Over time, such vestigial habits and understandings may have solidified into moral norms—even after the arrival of telescopes and birth control pills means the old ways no longer make objective sense. If you are a conservative, preserving the norm may nonetheless come to feel like an end in itself. And you will soon end up a very angry person indeed. For the word that the rest of the world that is not conservative attaches to these processes is “progress,” and the non-conservative world judges it an inherently desirable thing—the kind of thing the powers that be require children to learn about in school.

Public schools are where young people encounter ways of being and thinking that may directly contradict those they were raised to believe; there really is no way around it. Schools are where future adults receive tools to decide which ideas and practices to embrace and which to reject for themselves. Schooling, done properly, is the opposite of conservatism. So is it any wonder it frequently drives conservatives berserk?

The panics have unfolded like clockwork, in just about every decade of the twentieth and twenty-first century. You can see it in the titles of books and pamphlets going back a hundred years: Hell and the High School (1923); They Want Your Child! (1948); Brainwashing in the High Schools: An Examination of Eleven American History Textbooks (1958); What They Are Doing to Your Children (1964); Is the Schoolhouse the Proper Place to Teach Raw Sex? (1968). Even the dry bureaucratic version propounded by Ronald Reagan’s most conservative cabinet member, Education Secretary William Bennett, sounded the same high-pitched culture alarms when it declared in a report on school performance that the United States was A Nation at Risk (1983).

Really, the only thing mysterious about this long tradition of backlash is why, every time it has happened in our own lifetimes, does it feel as though liberals are responding like it’s the very first time, with no effective playbook to draw on to fight back? They tend to respond, well, like liberals, with open minds: maybe these conservatives sort of have a point? So perhaps some good-faith negotiations are in order: maybe if we accept certain of their proposed reforms that seem sound, society and its schools will emerge even stronger, and then some of the acrid divisions will abate . . .

To understand the problem with this reasonable-seeming solution, consider a case study from more than forty years ago, with the cultural earthquake of the 1960s still visible in the rearview mirror and the Reagan presidency just over the horizon. It can help us understand how reasonable reform is never the goal of these crusades. Give them an inch, and they will take a mile. Because ultimately, what they’re after is crushing the power of their children—and all of ours—to choose their own life: to, in other words, acquire the ability to become free.

Connaught “Connie” Marshner was a young staffer at Young Americans for Freedom in the early 1970s when she successfully launched a grassroots letter-writing campaign that helped spur President Richard Nixon to veto the only bill for a national childcare system ever to pass Congress. The language of this anti-daycare campaign presaged that of the “pro-family movement” (Marshner’s coinage) that took shape later in the decade, led by the Rev. Jerry Falwell and the Moral Majority, which helped Ronald Reagan get elected. Sending children off to state-sponsored institutions, at ever younger ages, intoned Nixon in his 1971 veto message, would subvert “the family in its rightful position as a keystone of our civilization,” committing “the vast moral authority of the national government to the side of communal approaches to child rearing over against the family-centered approach.” Seven years later, Marshner—now a staffer at the Heritage Foundation—published her first book, whose first chapter included the following passage:

Mothers have long observed that after the child starts school, the rest of the family starts catching more colds and flus. But other forms of disease are not so evident.

What about the personality traits that start developing? What about the dissatisfaction with family rules and routines? What about boredom with learning loss of curiosity about ideas and the world at large? Why do children suddenly begin to complain about responsibilities toward little brothers or sisters? Why do they resent doing accustomed chores? Why does off-color language or unfamiliar slang suddenly crop up in a child’s conversation?

As childhood yields to preadolescence and adolescence, and the condition gets worse, parents are told that these symptoms indicate normal stages of maturation. But when a mother is told by her high schooler, ‘You don’t know what’s right and wrong for me’ or ‘You don’t really care about me,’ she knows in her heart that it is something more than youthful Sturm und Drang that is causing the anguish. It is not biologically mandated for human offspring to turn against their parents. But all the kids on the block are acting that same way, so Mrs. Middle America figures she must be oversensitive . . . until something provokes her to take a closer look at her children’s public schools.

The book was called Blackboard Tyranny, and its roll call of horrors uncannily echoes that of all those frenzied books, articles, and pamphlets going back at least a hundred years—right up through the hippie-punching sloganeering of right-wing parents today. Marshner’s next section takes on “The New Illiterates,” supposedly turned out by today’s public schools (a pet theme of A Nation At Risk, and the kicker of one of Newt Gingrich’s best-known doom-laden nineties talking-points: that “It is impossible to maintain civilization with 12-year-olds having babies, with 15-year-olds killing each other, with 17-year-olds dying of AIDS and with 18-year-olds getting diplomas they can’t even read”).

Marshner was just warming up. Her next chapter, “Education As Social Reform,” laid out just how far afield public education had drifted from the simple verities of the sort of pedagogy that should be making America great: “Ancient history used to consist of facts, with appropriate illustration in the textbook, of pyramids, the Nile, and so on,” she lamented. “How does a typical lesson in today’s ancient history class run? It discusses at great length the miserable position of the Egyptian slaves, how exploited they were, how they had no rights and no means of redressing grievances.” (Critical race theory, anyone?) And through all this indoctrination, Marshner breathlessly reported, children were coddled into a state of intellectual suffocation by what Christian fundamentalists of her time dubbed the “messianic state.” “Fifteen years ago, nobody had heard of something called ‘learning disability’; by 1975, at least five million children in America were considered ‘learning disabled.’ What does it mean? Nothing, except that the child in question is different from most children.”

And at the heart of all this cunning social engineering and malevolent brainwashing, needless to say, was a shadowy cabal—an “education Establishment” that exhibited a vicious, all-devouring will to power. “What Happened to Local Control?” Marshner demanded in a chapter heading that could double as a Glenn Youngkin campaign slogan.

Then as now, any responsible good-faith investigator could surely find plenty of verifiable practices at some individual schools—and even school systems—that might seem unreasonable, perverse, and irresponsible. Then as now, some liberals, presuming good faith among ideologues like Marshner, could be expected to earnestly wonder whether conservatives didn’t have a bit of a point. Maybe the Democrats did lose the 2021 Virginia governor’s race because this whole critical race thing has gotten out of control. And all their culture-war opponents are asking for is “parents’ rights”—to be able to look into what their own kids are learning. What’s so dangerous about that?

The long passage I quote above from Marshner, though, gives the game away: there is no good-faith negotiation to be had.

The only thing mysterious about this long tradition of backlash is why, every time it has happened in our own lifetimes, does it feel as though liberals are responding like it’s the very first time?

There isn’t a parent on earth who doesn’t experience some trauma when sending a child off to school for the first time . . . and, just so, there’s also no parent who, thirteen years later, will send a kid to college without fearing that someone unrecognizable would come back. Define a liberal as a parent who manages to get over it. Define a conservative as, well, someone like Connie Marshner—who reserved her most frenetic prose for the claim that the “constitutional right to family privacy” was under siege by school practices intended to, God forbid, preserve and enrich children’s mental health. “‘Self-actualization’ is jargon; ‘doing your own thing’ is the popular translation.”

In the primary literature of the 1970s and ‘80s Christian right, you will rarely find more passion exercised than when the subject is psychologists in schools. That’s why the most fire-breathing partisans of the right-wing school wars kept on introducing versions of a bill that, in its 1978 form introduced by Senator Orrin Hatch, was called the Protection of Pupil Rights Amendment. It sought to ban any actions in any federally funded school that “infringe upon or usurp the moral or legal rights or responsibilities of parents or guardians with respect to the moral, emotional, or physical development of their young children.” In other words, it sought to kill off any possibility that anyone outside the home might give children the tools to become themselves.

And as usual, a reasonable response is to grant that folks who think this way sort of have a point. I remember a shrink once told me, “A parent’s job is to do themselves out of a job”—to spur individuation; to make us autonomous selves; to let us do, think, feel, and act however we want, whatever the patriarchs who handed down the ancient moral codes may say about it. Love them, sure; but also leave them. And this, to a conservative parent, is the ultimate terror—it’s why they dream they can somehow stand athwart their own child’s individuation process yelling “Stop!”

That, ultimately, is what the school wars are all about. It explains why the molten core of this year’s eternal return of the public school culture fracas is “social-emotional learning.” In real life, this phrase denotes a paradigm to improve children’s self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, social awareness, and relations skills that has been proven again and again to produce better educational outcomes and student behavior. But in the dreamscape of right-wing strategist Christopher Rufo, the field marshal of this particular crusade, social-emotional learning is a sinister virus burrowed deep within the messianic state’s math textbooks. And what is its ultimate aim? To “soften children at an emotional level, reinterpret their normative behavior as an expression of ‘repression,’ ‘whiteness,’ or ‘internalized racism,’ and then rewire their behavior according to the dictates of left-wing ideology.”

It will always be something. It can be teaching kids evolution; teaching kids how bodies get pregnant and how to prevent it; teaching them how the moral arc of history may be long, but that they can help bend it toward justice. To some conservatives, it all will just sound like one more way the cruel world connives to snatch their babes from their arms and take them far, far from the home. They’ll call it “the therapeutic state invading the home,” as Connie Marshner did in 1971 when she was organizing against government-sponsored preschools. Or “an insidious attempt to replace our periods with their question marks,” as a fundamentalist parent told Village Voice reporter Paul Cowan in 1974 when he came to Kanawha County, West Virginia, to investigate why right-wing terrorists had dynamited the local school board building and thrown firebombs into empty classrooms to protest the imposition of liberal textbooks. Or force teachers to “serve as psychologists,” as Rufo now brays, “which they are not equipped to do.”

The education of children must always be somewhat painful for a parent: it does them out of job. And for conservatives, this invitation for children to think for themselves will always be a virus. It will always feel like “indoctrination.” It will always be some establishment conspiracy arrayed against them.

That’s why I don’t think conservatives, at least some of them, will ever stop trying to burn down public education. Sometimes they even admit it: “I hope to see the day when, as in the early days of our country, we don’t have public schools,” Jerry Falwell said in 1979, though he denied it when confronted with the quote. “The churches will have taken them over again, and Christians will be running them.”

There is only one way to answer this attitude—an answer that can never be negotiated away: Assert with pride that the purpose of public education in our republic is to make us free, self-determining individuals. For some of us, that process will send us running far from our natal villages, never to return. That’s just life. That’s the real world. Although for some people, it will draw them closer to the world we came from than they’d imagined possible. It may even graduate them as conservatives. Conservatives should welcome the risk—for an identity that is freely chosen will always be stronger than one that’s produced under compulsion. And once they savor this sort of freedom for themselves, perhaps they’ll be less histrionic about granting it to others in turn.

Rick Perlstein is a historian and author of Reaganland: America’s Right Turn, 1976-1980.