When the QAnon movement first came on the political scene in 2017, its conspiracist claims were so preposterous that few took it seriously. Even for a right-wing fringe long steeped in unhinged conspiratorial speculation on every subject from 9/11 and Sandy Hook to Barack Obama’s birthplace, QAnon seemed a tinfoil hat too far. This internet-bred political theology holds that high-level Democrats, Hollywood figures, and business leaders are operating a global cannibalistic satanic child-sex-trafficking ring of epic proportions. Its mortal foe is said to be movement hero Donald J. Trump, who, at the time of QAnon’s first appearance, was supposedly using the powers of his presidency in a secret plan that would, any minute now, end in a flood of blood when he rounded up the evil-doers and initiated mass executions of them all.

Clues to the plan (known as “The Storm”) and its targets were dropped on the 8-chan (now 8-kun) message board by an anonymous figure known as Q, who is said to have a high-level security clearance, but is working against the “Deep State” from within. Some QAnoners believe Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Michael Flynn, Trump’s first national security adviser and a QAnon-coddler, to be Q—even after ally-turned-nemesis Lin Wood, a QAnon-promoting attorney involved with efforts to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential election, leaked a tape of Flynn saying that QAnon was a disinformation campaign. In July 2020, Flynn posted a video to Twitter of himself and members of his family reciting the QAnon pledge, which includes the movement slogan, “Where we go one, we go all.” (In a lawsuit filed against CNN, which reported on the incident, Flynn’s brother and sister-in-law, Jack Flynn and Leslie Flynn, contend that the quoted phrase coincidentally happens to be the Flynn family motto.)

On the other hand, filmmaker Cullen Hoback, in his HBOMax documentary, posits the notion that the Q character is the fictional creation of Ron Watkins, son of Jim Watkins, who happened to be 8chan’s administrator at the time of Q’s first appearance and went on to own the platform. Today, Ron Watkins is a Republican candidate for Congress in Arizona’s 2nd District, where he is running in an August primary.

Another narrative thread in the Q-niverse asserts that John F. Kennedy Jr. is still alive. The rest of the ever-expanding QAnon ecosystem holds pretty much every anti-semitic conspiracy theory going back to the time of the czars (and beyond, if you count the child-predator theme as blood libel), as well as portents of a coming one-world government and New World Order, in addition to the ever-present communist threat, summoned from John Birch Society lore.

Right-wing leaders aim to turbo-charge the conspiratorial and evangelical thugocracy on which they’ve come to depend in the age of Trump.

Asked in August 2020 how he felt about the QAnon movement’s embrace of him, Trump said, “I’ve heard these are people who love our country.”

When an NBC News reporter pressed Trump on the movement’s claim that he’s fighting a ring of satanic, cannibalistic child-sex predators, the then-president retorted, “Is that supposed to be a bad thing?”

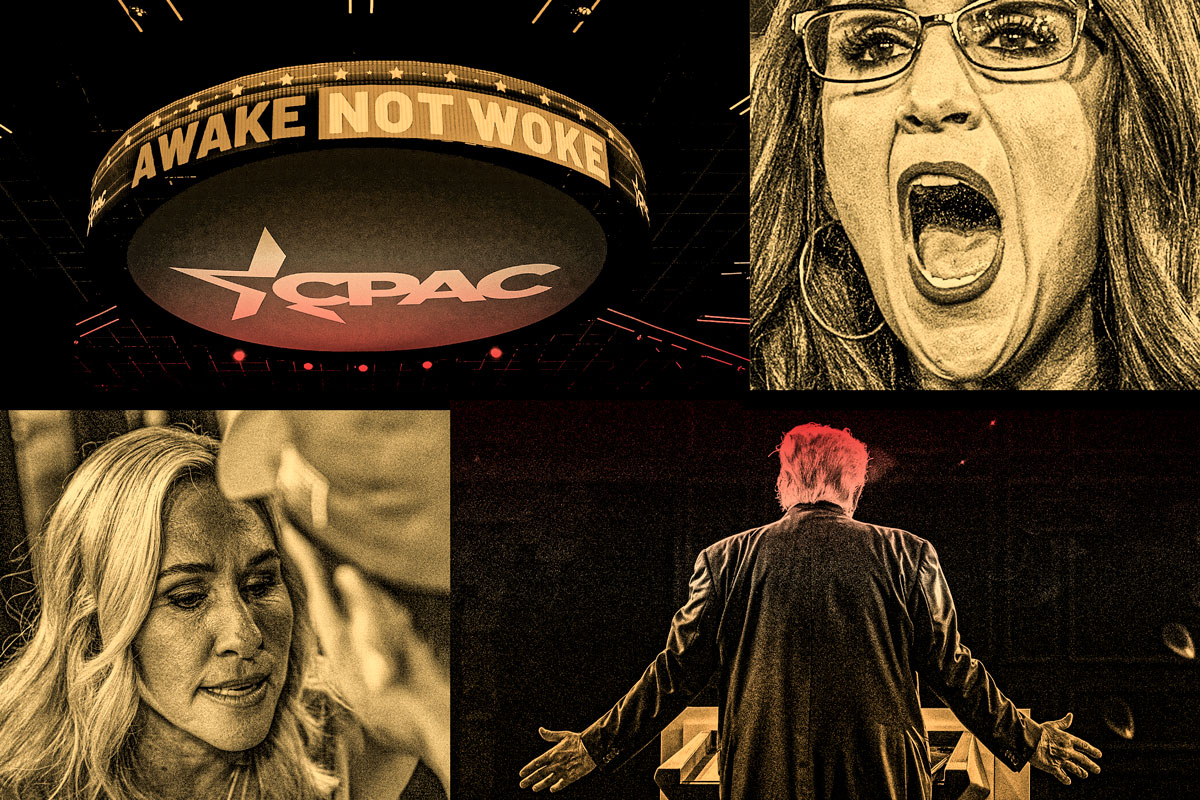

Today, members of Congress are feeding the phantasmagorical narrative—some, like Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, R-Ga., who often delivers fiery Q-friendly orations on the House floor and in the broader mediasphere, have become legislative mascots for the movement. This spring, New York GOP Rep. Elise Stefanik tweeted out an attack on “pedo grifters” in the Democratic Party establishment; in the ensuing flurry of media coverage, her harried aides tried, unconvincingly, to explain that the lawmaker used “pedo” as a reference to children (you know, as in, “The pedos are our future”).

But appeals to the GOP’s burgeoning QAnon base are surfacing in more august and influential settings as well—such as the March confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, which doubled as a forum for insinuating questions and grandstanding speeches about pedophiles from several GOP senators on the Senate Judiciary Committee. This dog-whistle chorus was all too easy for many in the political press and other establishment figures to overlook—particularly since casual followers of right-wing messaging could readily mistake it for traditional “soft on crime” attacks on Democrats, or one more instance of performative racism with an accomplished Black woman as its object.

These more familiar narratives were still very much in play during the Jackson hearings, but it’s crucial to focus on the QAnon subtext here as a vital clue to the kinds of conspiratorial call-outs already favored by the GOP’s most ardent culture warriors. The labored questioning that Jackson withstood about her record in cases relating to pedophilia (including a decades-old law-review article on mandatory sentencing in cases of child sexual abuse) was much more than an inquiry into her judicial philosophy. As the committee’s best-known conservative lawmakers—Sens. Josh Hawley, R-Mo., Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and Lindsey Graham, R-S.C.—homed in on Jackson’s sentencing counsel in such cases, the QAnon subtexts came to the fore; this trio of inquisitors seemed keen to convey to QAnon believers that the senators are on their side in the crusade against liberal child predation. (Never mind, of course, that Jackson’s sentencing record in child sexual-abuse cases was well within the norm for the federal bench.)

Indeed, the accusatory QAnon-coded questions from right-wing senators drowned out much of the actual constitutional mission of the Senate panel. Washington Post columnist Dana Milbank noted that during the confirmation hearings for Jackson, the phrase “child porn” or its variants predominated in the hearing transcript, while other key areas of high-court jurisprudence barely rated any extended discussion:

In four days of Supreme Court confirmation hearings for Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson, the phrase “child porn” (or “pornography” or “pornographer”) was mentioned 165 times. There were also, according to transcripts, 142 uses of “sex” (“sexual abuse,” “sexual assault,” “sexual intercourse,” “sex crimes”), 15 of “pedophile,” 13 of “predators,” 18 of “prepubescent” and nine of general pornography.

There were only 30 mentions of the First Amendment and 12 of the Bill of Rights.

“Judge Jackson’s view is that we should treat everyone more leniently because more and more people are committing worse and worse child sex offenses,” said Hawley at the March 22 opening day of hearings, pointedly adding that “we’ve been told things like child pornography is actually all a conspiracy [theory]; it’s not real.”

Graham piled on, saying, “Every judge who does what you’re doing is making it easier for the children to be exploited.”

Not to be outdone, Cruz said of Jackson’s career on the bench, “I also see a record of . . . advocacy as it concerns sexual predators.”

Others on the committee who sounded the same “child predator” theme during the confirmation hearings include Marsha Blackburn of Tennessee, Tom Cotton of Arkansas, and Mike Lee of Utah.

But please don’t mistake this pandering for mere appeasement of the QAnon component of the Trumpian base. With the midterm campaign season looming into view, the senators are doing more than simply signaling solidarity with the Q-crowd; they aim to turbo-charge the conspiratorial and evangelical thugocracy on which they’ve come to depend in the age of Trump.

Media Matters for America, a liberal research nonprofit, reports that more than 65 QAnon adherents or promoters are candidates for congressional seats in the current round of primary races. (In Ohio, QAnon sympathizer J.R. Majewski won his May 2 primary to become the GOP nominee for the state’s 9th Congressional District.) Dozens more are running in local- and state-level elections, including positions involving the oversight of elections themselves. The mobilization of scores of Q-aligned candidates on the right also foreshadows another militant campaign of potential ballot disruption in 2022, now that the false narrative of election theft is etched in the bones of QAnon believers. Longtime watchers of right-wing direct-action campaigns are already warning against the specter of at least some QAnon-inspired chaos at polling stations this November.

In June 2021, the Brennan Center for Justice, a liberal think tank, issued a report by Michael Dorf analyzing the threat of political violence by those Dorf calls “insiders”—radicalized members of an established political party (namely, the Republican Party). In his assessment, he includes a range of “inside” actors, from members of militia groups to QAnon believers. Dorf’s report, “Disaggregating Political Violence” issues a stark warning:

We are now witnessing a resurgence of insider violence by substantial numbers of supporters of one of the two major political parties. Whereas outsider violence chiefly poses the risk of a breach of the peace, insider violence poses that risk as well as a threat to democracy itself . . . Counterspeech against this movement has limited utility, as the movement aims less to persuade than to intimidate.

QAnon has already shown a propensity for provoking violence in some of its believers, and its central promise is a gory culture-war catharsis culminating in the mass execution of Democrats. Meanwhile, the Public Religion Research Institute found that 30 percent of Republicans, and 39 percent of Americans who believe the 2020 election was stolen from Trump, said they agreed with this statement: “Because things have gotten so far off track, true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

When Trump supporters attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, a striking segment of the insurrectionists were wearing QAnon-themed attire. And in the aftermath of the attempted coup, Republican leaders of both the House and Senate denounced the president for failing to call off the marauders.

The mobilization of scores of Q-aligned candidates on the right also foreshadows another militant campaign of potential ballot disruption in 2022, now that the false narrative of election theft is etched in the bones of QAnon believers.

“President Trump claims the election was stolen. The assertions range from specific local allegations to constitutional arguments, to sweeping conspiracy theories . . .” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., on the floor of the joint session as Congress reconvened on Jan. 6, 2021, after the insurrectionists had been cleared from the chamber.“But over and over the courts rejected these claims, including all-star judges, whom the president himself has nominated,”McConnell added.

For good measure, Graham, a sycophantic Trump fan and grandstander supreme, appeared to signal a long-overdue break with the president: “All I can say is: Count me out. Enough is enough.”

A week later, during the House debate on Trump’s second impeachment, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy seemed to join the growing body of sudden Trump-skeptics on Capitol Hill, even as he argued against impeachment in favor of a censure vote.

“The president bears responsibility for Wednesday’s attack on Congress by mob rioters,” McCarthy said in the Jan. 13, 2021, debate on the House floor. “He should have immediately denounced the mob when he saw what was unfolding. These facts require immediate action by President Trump.”

Then something funny happened. Two weeks later, on Jan. 28, McCarthy visited Trump at the now-former president’s Mar-a-Lago compound in Florida. He came back an apparently changed man, willing to give the vanquished leader of his party the benefit of the doubt.

Following the Trump-McCarthy tête-á-tête, Trump’s political action committee, Save America, issued a statement that said the two “discussed many topics, number one of which was taking back the House in 2022.” It went on to assert (in a way that sounded a lot like a threat), “President Trump’s popularity has never been stronger than it is today, and his endorsement means more than perhaps any endorsement at any time.”

McCarthy issued his own statement, saying, “Today, President Trump committed to helping elect Republicans in the House and Senate in 2022,” McCarthy said. “A Republican majority will listen to our fellow Americans and solve the challenges facing our nation.”

McCarthy’s capitulation to Trump’s megalomania and conspiracy-mongering produced dire political consequences on the right. For starters, the Jan. 6 debacle of the Capitol invasion made it all too clear that deferring to Trump’s rampaging persecution complex also meant, at a minimum, giving a pass to the QAnon rank-and-file, and their dangerous, baseless and incendiary claims.

The practical impact of McCarthy’s Trumpward turn didn’t take long to materialize. Four months later, the GOP’s congressional leaders expelled Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming from their ranks with McCarthy’s blessing. (Meanwhile, McCarthy’s counterpart in the Senate, Mitch McConnell, had also quietly relinquished his criticisms of Trump’s flagrant abuses of power on Jan. 6 after the political climate shifted.)

Thus the devastating assault on the Capitol, and American democracy writ large, passed into the political narrative that reliably distanced and diminished dissent over the GOP’s descent into authoritarianism. It could now be safely treated as one more intramural squabble among Republican lawmakers and consigned into the memory hole of horse-race commentary, together with so many other lurches to the hard right over the past four decades. It’s difficult to calculate the costs of this capitulation, since by rights the aftermath of Jan. 6 should have been the perfect moment for the GOP to shake off Trump. Yes, any such moment of reckoning would have forced an upheaval in the party, but it would have been a minimal blow struck for democratic norms and procedural commitment to certain undeniable public truths–starting with the outcome of free and fair elections. Instead, the reckless neglect of party leaders McCarthy and McConnell guaranteed that the apostles of the deranged and apocalyptic QAnon faith would securely remain fastened to the base of the Trump-era GOP. In other words, the Republican party’s leadership caste had now thrown in with white nationalist true believers who spend their weekends trading blueprints for gallows and sharpening the tips of the poles that carry their MAGA flags.

This meant, among other things, that McConnell, McCarthy et al. were leaning into conspiracy narratives that had already started to gain serious traction on the right under Trump. In September 2020, a DailyKos/Civiqs poll showed that 56 percent of self-identified Republicans rated the QAnon conspiracy theories as true or partly true, and a Pew survey from around the same time found that “roughly four-in-ten Republicans who have heard of QAnon (41%) say it is a good thing for the country.” A more recent report by the Public Religion Research Institute shows that support for QAnon beliefs has held steady over the course of 2021. In its year-long survey, PRRI determined that 25 percent of Republicans were full-on QAnon believers.

This prolonged profile in cowardice in the leadership ranks of the GOP helped to fatally tip the balance of power Qward on the right. After all, the Civiqs poll essentially found that at least 44 percent of Republicans did not see QAnon narratives as true, while the Pew survey found that 50 percent of QAnon-aware Republicans thought the movement was bad for the country. Today’s GOP, under the continued sway of the Trump movement, has chosen to bet against these voters, together with any swing voters inclined to shun the racialized paranoia of QAnon.

This was all a flashback to the grim spectacle of 2016, when Republican leaders lined up behind Trump once he won the nomination. Sure, Trump was dangerous, party leaders reasoned back then–but the danger he posed could redound to the GOP’s benefit, mobilizing new militant partisans of race-themed culture warfare, who might otherwise be prone to skip voting. In the wake of such cold political calculations, it’s no great surprise to see the enduring appeal of the follow-on prostrations of party leaders in the aftermath of Jan 6. In raw structural terms, it’s difficult to see how the GOP, a minoritarian entity, can continue to maintain (let alone expand) its power without injecting fear—not simply into its base, but into the whole of the body politic. The party’s freshly mobilized fear-motivated white base could be stoked by anxieties over the prospect of losing its place in society’s pecking order, while the chaos fomented by the true believers of the Big Lie of the stolen 2020 election could work to depress and discourage turnout among saner and less excitable voting demographics. Fear is contagious—and with Trump embracing QAnon and endorsing QAnon-linked candidates, the danger posed by the authoritarian, conspiracy-driven movement became all the more potent. The de facto slogan of GOP leadership became: If you don’t have the courage even to try to beat ‘em, join ‘em, and turn their malice to your electoral favor.

Danger is the Republican brand—not only in stoking existential fears among the party faithful, but in inspiring a posture of violent culture-war confrontation.

A scant month after the January 6 insurrection, the Atlantic’s Ronald Brownstein asked historian Matthew Dallek to compare the standing of QAnon within the GOP to the challenge the party faced in 1964 with the injection of the John Birch Society’s conspiracy-theory narratives into Republican campaigns:

There were a lot more Republican leaders, and their constituents, who attempted to push back then than there are now,” says Matthew Dallek, . . . the author of an upcoming history of the John Birch Society. “To a large extent, the people who have inherited the Birch legacy today, I think, are more empowered [and] more visible within the Republican Party. There is much less criticism; there is much less of an effort to drum them out; there is a much greater fear of antagonizing them. They are the so-called Republican base.

The embrace of militant conspiracy extends well beyond QAnon. Indeed, if you look at the cultural identifiers of today’s Republicans, many pose real life-or-death dangers to their fellow Americans: permitless gun-carrying rights, defiance of public health measures during a deadly pandemic, attempted repeals of legislation through which millions of Americans obtain health insurance, forced pregnancies despite the existence of safe procedures for ending them, health-care bans specific to the needs of transgender young people. Add to that the current QAnon-influenced campaign to smear public school teachers and queer people as “groomers”—a term associated with the coercive behavior of pedophiles—and you have mainstream political leaders on the right collaborating in a campaign of orchestrated political slander that could readily prompt some believers to consider killing the designated targets of such slander. Election officials who dissent from other articles of MAGA orthodoxy are also facing death threats. It would not be an exaggeration to say that “danger” is the Republican brand—not only in stoking existential fears among the party faithful, but in inspiring a posture of violent culture-war confrontation toward people belonging to the movement’s rapidly burgeoning list of cultural and political outgroups. When they shout “Freedom,” think “danger.”

The exploitation of fear and conspiracy speculation is nothing new in modern politics. But the GOP’s embrace of QAnon represents a dramatic ratcheting-up of the American right’s half-century-long persecution complex–and is now steeped in much the same bedrock outlook of highly aggrieved racial resentment.

As outlandish as the core doctrines of QAnon may have seemed when they first emerged on the political scene, they didn’t come out of nowhere. The history of right-wing extremism teems with many influential figures who have updated and modernized the paranoid neo-Confederate mindset of what was formerly known as the paleoconservative right for deployment in today’s openly racialized culture wars—but one key player at the heart of this transformation was the petroleum magnate and right-wing paterfamilias Fred Koch. Early in the postwar mobilization of the conspiratorial right, the patriarch of the Koch Industries fortune was one of the founding members of the John Birch Society (JBS)—a right-wing movement organization that mass-produced a vast, rolling conspiratorial persecution complex through the publications and activist campaigns of JBS leader Robert Welch, Jr. Under Welch’s guidance, the Birch organization detected the insidious threat of communist takeover at every conceivable turn in American life; indeed, Welch published a book-length tract arguing that no less an eminence than President Dwight D. Eisenhower was a duly authorized agent of communist subversion. With the advent of school desegregation and the first wave of civil rights activism, Welch also mounted a libertarian assault on the ideals of racial equality—a campaign that would coincide with Barry Goldwater’s capture of several key southern states in his otherwise crushing loss to Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964—which would, in turn, supply the roadmap for Richard Nixon’s successful capture of the White House four years later with the infamous “Southern strategy” tailored to fan the flames of racism for political gain.

Like QAnon, the John Birch Society was dismissed in most respectable circles of elite opinion. But like today’s paranoid right, the belief system of the Bircher faithful was nestled alongside the operations of the conservative mainstream—and gradually, their intellectual legacy came to overtake the institutions safeguarded by their erstwhile antagonists. The elder Koch’s own legacy traces this shift in the critical world of political funding and movement-building. Fred’s two chief heirs, the brothers Charles and David Koch, took up the mantle of their father’s paranoid libertarianism—together with the racialized resentment that stoked Bircher activism at the grassroots—providing the infrastructure for the Tea Party movement at the outset of the Obama presidency.

Under the umbrella of the Koch-funded group Americans For Prosperity, the central elements of the Tea Party movement came together under a well-orchestrated and potent theology of political victimization. The nascent network of Tea Party activism attracted a hard core of followers who espoused all manners of resentment-based conspiracy-theory claims, including the notions that then-President Barack Obama was a closet communist, and that the birth certificate of America’s first Black president was a fraud—a cause taken up with unmistakable racialized rancor by Donald Trump.

By the 2010 midterm cycle, the Tea Party had consolidated its position as the focal point of movement energy on the anti-Obama right. And in remarkably short order, the Koch network supplanted the legacy infrastructure of the Republican Party, leaving the GOP dependent on its data operation, dark money networks, field organizing and electoral strategy: pretty much everything, in short, that any right-leaning political candidate might need.

At a 2009 Americans For Prosperity event, David Koch took care to highlight the pivotal role that AFP was already playing in galvanizing opposition to Obama’s governing agenda. His analysis was spot-on: AFP had stormed to the vanguard of organized resistance to the passage of the Affordable Care Act, a backlash response to Obama’s election that used racism and paranoia about health-care reform to stoke the rage of the movement’s self-styled “patriots.” As Congress debated the healthcare overhaul, AFP organized right-wing activists to disrupt the town hall meetings conducted by members of Congress in their respective districts and states. The disrupters’ behavior often bordered on violence; many Tea Party backers showed up to town halls armed and shouted threats to Democratic lawmakers and their supporters.

The GOP’s embrace of QAnon represents a dramatic ratcheting-up of the American right’s half-century-long persecution complex–and is now steeped in much the same bedrock outlook of highly aggrieved racial resentment.

After the GOP retook the House behind a wave of Tea Party activism, this new mood of belligerence in the face of alleged sinister liberal plots to take over the hallowed institutions of the American market order became the standard rhetorical stock in trade on the right. In 2010. In short order, a new network of Tea Party organizers arose to take advantage of the momentum built by the Koch political funding combine. In an essay for Newsweek, conservative writer Jonathan Kay described his experience at a 2010 convention of Tea party activists in Nashville:

Within a few hours in Nashville, I could tell that what I was hearing wasn’t just random rhetorical mortar fire being launched at Obama and his political allies: the salvos followed the established script of New World Order conspiracy theories, which have suffused the dubious right-wing fringes of American politics since the days of the John Birch Society.

This world view’s modern-day prophets include Texas radio host Alex Jones, whose documentary, The Obama Deception, claims Obama’s candidacy was a plot by the leaders of the New World Order to “con the American people into accepting global slavery.”

And as the newest iteration of the conspiratorial right was coalescing, it attracted some policy entrepreneurs from past orchestrated campaigns of right-wing conspiracy-mongering. The career of culture-war-provocateur Jerome Corsi is a revealing case in point. The one-time correspondent for Alex Jones’s enormously influential and disinformation-spewing InfoWars radio franchise first made his mark as a co-author of 2004’s Unfit for Command: Swift Boat Veterans Speak Out Against John Kerry, a right-wing campaign hit job that targeted Kerry’s leadership as a lieutenant in the U.S. Navy during the Vietnam war. By 2007, Corsi was breathlessly chronicling the supposed plot to abolish American sovereignty and launch a nebulous, elite-run trading bloc called North American Union in its place—a pet conspiracy flogged by the Birch Society in Robert Welch’s heyday–in a title-says-it-all tract called The Late Great USA: The Coming Merger With Mexico and Canada. By 2008, Corsi was devoting himself to finding the true story of presidential candidate Barack Obama’s birth certificate. He would go on to play a go-between role on behalf of self-described dirty trickster and Trump ally Roger Stone in gleaning information on Wikileaks founder Julian Assange’s plans for the hacked campaign emails from Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

In September 2008, veteran right-wing organizer Howard Phillips told me he was in frequent touch with Corsi, who was in Hawaii doing alleged birth certificate research. (Corsi also wrote a book for the 2008 presidential election season, The Obama Nation: Leftist Politics and the Cult of Personality, which reached the top of the New York Times Bestseller list for a time.)

On New Year’s Eve of 2017, Corsi appeared on Alex Jones’s InfoWars show to discuss QAnon with the host—and marshaled his own conspiracy-spotting credentials as alleged inside confirmation of the Q movement’s unhinged worldview:

“QAnon is clearly an intelligence source of one kind or another—has inside information,” Corsi said to Jones. “I mean, I’m able to decode it because of the background I’ve got in intelligence, and QAnon is validating the things you’ve been saying for years. And that’s where the affinity comes; there’s background here that validates all the points you’ve been making about the globalists.”

The nexus of Tea Party leadership on the right took center stage in the build-up to the January 6 insurrection seeking to overturn Joe Biden’s Electoral College majority in Congress. Amy Kremer, the famously combative former chair of the Tea Party Express, a PAC that leveraged the Tea Party movement for donor dollars with a traveling road show in 2009, was a principal organizer of 2021’s so-called Stop the Steal rallies. Less than a month before the 2021 insurrection, Kremer’s Trump-backing organization, Women For America First, staged a rally in Washington, D.C., that featured QAnon fellow traveler Michael Flynn as a star attraction. Women for America First went on to sponsor the Jan. 6, 2021 rally on the Ellipse where Trump told his supporters to “fight like hell,” and Trump attorney Rudy Giuliani suggested that Trump’s enemies would be subjected to “trial by combat.”

Another key Stop the Steal leader was alt-right impresario Ali Alexander, who also cut his teeth working for Tea Party candidates. Alexander is tight with Jack Posobiec, who in 2016 promoted the Pizzagate conspiracy theory, which helped launch QAnon’s claim of a massive pedophile ring made up of prominent Democrats.

On March 22, during Jackson’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing, Pizzagate promoter Posobiec tweeted a false description of Ketanji Brown Jackson’s testimony regarding her sentencing criteria for consumers of child pornography. On Mothers Day weekend, he issued a strange series of tweets about the demise of Pizza Hut dine-in restaurants as a metaphor for the decline of American culture, perhaps harking back once more to QAnon’s Pizzagate origin story.

The power of conspiracy theories is seductive to those who feel their lives to be somehow out of control, or who construe changing demographics and social trends as a threat to their own precarious social standing. There are countless stories of how QAnon and related conspiracy theories have ripped up families when one family member falls down the QAnon rabbit hole. It’s not just a handful of crazies who pose this danger; it’s the legions of regular people who subscribe to the conspiracy narrative.

In his oft-cited but routinely misunderstood 1964 essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” historian Richard Hofstadter began his piece with a none-too-subtle nod to the Goldwater-bred derangements in Republican politics:

[T]he idea of the paranoid style as a force in politics would have little contemporary relevance or historical value if it were applied only to men with profoundly disturbed minds. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant.

Today, by contrast, Republican leaders are taking their cues from the “more or less normal” rank-and-file members of the QAnon movement, rather than from the ravings of a latter-day Goldwater or Robert Welch seeking to choreograph the course of public opinion from the top down. And that’s precisely why QAnon is dangerous, in a way that Hofstadter and other mid-century students of the radical right could never have anticipated.

Danger is the main feature of today’s Republican brand. As they telegraph open support for the movement’s pet conspiratorial delusions, party leaders are apparently set on breaking the most basic guarantees of the American social contract–together with the minds of true-believing culture warriors on the right.

Adele M. Stan is a writer on many subjects and a long-time chronicler of the modern American right.