With the World Health Organization’s announcement that the virus long known as monkeypox is to be renamed in less overtly derogatory fashion, it’s worth revisiting the West’s ugly track record of racializing disease—and dehumanizing alleged disease carriers as a result. It’s a centuries-old tradition that’s deployed pop culture and pseudo-scientific inquiry to shore up destructive discourses that fuse reactionary ideas about race, infection, and animalization.

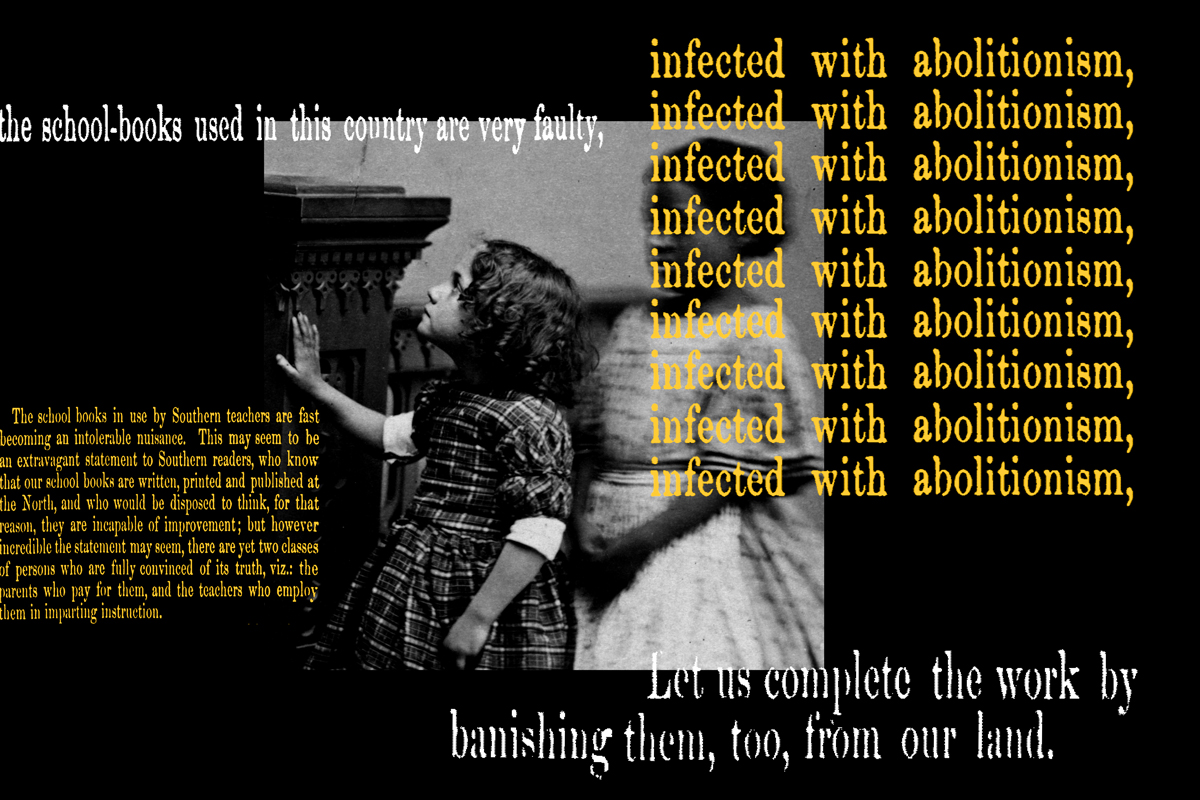

Let’s start with the comics. If you were to pick up the 1931 comic book Tin Tin in the Congo, you would see a shocking legacy of Belgian racism and colonialism: all the Congolese people in the panels of the comic are depicted as monkeys. Tin Tin’s creator, Hergé, did not invent this racist depiction; when the Belgians took over the Congo, they referred to locals as “macaques.” In 1854, Josiah C. Nott (a slaveholder in the American South) and George Gliddon published their pseudoscientific study of anthropology, Types of Mankind, which compared Black people to apes, orangutans, and chimpanzees. Nor is simianization—the depiction or description of human beings as monkeys—a forgotten relic of the colonial past. In the twentieth century, author Edgar Burroughs released a popular series of novels, starting with Tarzan of the Apes, which all featured a white man ruling over a bunch of Black humans who are depicted as bestial and simian. When Barack Obama became president of the United States in 2008, the Belgian magazine De Morgen chose to depict the first couple as monkeys.

The editors of De Morgen tried to dismiss the image as a satirical misfire—but the heart of simianization and animalization is serious and deadly. Both remain powerful and ugly forms of racist denigration, and bear testimony to a long tradition of white colonial conquest and racial subjugation—which hinged on the practice of demonizing non-white others as animalistic and therefore inherently inferior.

In light of this long-established and viciously racist history, you’d think international health bureaucracies would take special care to avoid language that keys into the tropes of simianization and animalization. But until recently, they haven’t. On May 13, the World Health Organization (WHO) and other health groups reported that cases of “monkeypox”—a virus that originated in West Africa—had surfaced in the United Kingdom and other European countries. Most published reports on this new viral threat (which in a pandemic-infused world, this means almost every news source) showed a picture of Black hands covered in boil-like eruptions. Since this initial round of coverage, cases of the virus have increased—as has alarm over Africa-bred infection among largely white Western Europeans. Recent data has the United Kingdom reporting the highest number of cases at more than 800, and Spain and Portugal following with more than 500 and 300, respectively.

Nonwhite populations can be readily demonized for bringing the specter of contagion and pestilence into the social orders ruled by white people.

Transmission of the disease usually takes place via sexual contact among infected people, but contact with particles of infected saliva or other bodily fluids can also pass it on. One key symptom of infection is an outbreak of liquid-filled rashes, akin to the smallpox virus, all over the sufferer’s body.

The virus is also not a new disease. On June 8, Tedros Ghebreyesus, executive director of the WHO, noted sardonically that “This virus has been circulating and killing in Africa for decades. It’s an unfortunate reflection of the world we live in that the international community is only now paying attention to monkeypox because it has appeared in high-income countries.”

Ostensibly the virus became branded as “monkeypox” when it was “discovered” in 1958 via two outbreaks in monkey colonies. The Danish scientists studying the monkeys noted the similarity between this disease’s symptoms and traditional smallpox outbreaks, and apparently thought monkeypox was an innocuous descriptor. The first human case of the disease was reported in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

This origin story echoes the familiar pattern of simianized language in white Western culture. The loose rationale for a name that overtly simianizes—connects monkeys and Black Africans who first got the disease—seeks to appear inadvertent, in spite of this language’s all too legible history as a colonialist and racist legacy. Defenders of the nomenclature insist nonetheless that the term “monkeypox” isn’t signifying that Black Africans (as opposed to White Europeans) are more like monkeys. But this is again to ignore all relevant cultural and racial context: The disease led the news cycle in the first place only because it had broken out among white Western European populations. What’s more, advisories from the WHO and other health officials reinforced this unsubtle narrative of racial threat, deliberately noting that these new outbreaks all involve travel among, and contact with, Black people. This discourse verged uncomfortably close to the world of Tin Tin in the Congo, in which a dark-skinned “other” continent is a threat to white conceptions of normalcy and order—only with the additional panic over the licentious and hedonistic sexual practices of animalistic and demonic Black people.

Seen in this light, the name “monkeypox” serves a legitimizing function—a facts-are-facts affirmation of a racist origin story that will likely shadow the disease’s movement through traditional white media ecosystems. There’s another ominous precedent for this sort of associative racial panic: the advent of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, which was also pinned on Black people—and speculative theories of cross-species transmission with primates. That experience is a stark recent reminder of how readily nonwhite populations can be demonized for bringing the specter of contagion and pestilence into the social orders ruled by white people.

Consider one chilling case in point: the plight of Nushawn Williams, who is still doing time in a New York prison. In 1997, the then-21-year-old Williams pleaded guilty to charges of statutory rape (some of his partners, were under 18) and reckless endangerment in Jamestown, a largely white enclave in Chautauqua County in upstate New York. A number of Jamestown women, many of them white, complained of contracting AIDS after they’d had sexual contact with Williams. The State of New York, which had been considering attempted murder charges in Williams’ criminal trial, claimed—without evidence—that Williams had deliberately sought out contact with the women after he’d tested positive for HIV/AIDS.

Reporters in New York’s tabloid press hyped the story as a classic study—yet again—of unlicensed Black behavior as a menace to white safety, peace, and order. Headlines labeled Williams an “AIDS MONSTER.” As Philp Alcabes recounted in a Virginia Quarterly Review piece, other racist dispatches tagged Williams as an “AIDS-predator”, a “maggot”, “a bogeyman incarnate,” and a “dirtbag.” Still other panicked reports alleged that Williams had “preyed on schoolgirls” and had “hundreds of partners.” Here, in short, was “a guy who shot a number of people with a different kind of bullet” as one among countless lurid commentaries on the case put it. And once Williams was on the verge of completing his full 12-year term in prison in 2010, New York Attorney General Andrew Cuomo sent him back, citing his legal authority to condemn certain inmates to “indefinite civil detention.”

Williams’ case is an object study in how far white-led institutions, legal structures, and media outlets will go to reinforce the racist image of Black people as sinister and subhuman aliens, poised to contaminate white societies with disease. Nomenclature aside, it is no great stretch to see the ugly precedents set by the Williams case overtaking the present panic over the Congo-based virus that’s spreading in Western Europe. All the basic elements are already in place, with more health officials and media outlets conspicuously fretting over a pestilence from licentious Africans coming to menace the unassuming white populations of the UK or Spain. And as was the case for Williams, the alarm over “monkeypox” is likely to have a potent legitimating function, as a mass white media audience conditioned to think the contact with Black people could be a mortal threat can go on to adopt a whole body of related racist beliefs.

The name ‘monkeypox’ serves a legitimizing function—a facts-are-facts affirmation of a racist origin story that will likely shadow the disease’s movement through traditional white media ecosystems.

The racist logic of this public discourse is also likely to dictate the public health response going forward. As WHO Director Tedros observed when he noted the western press’s belated and self-interested attention to the disease, most of the resources now earmarked to stem its spread will not go toward saving Black people in the Congo or elsewhere; they will go to protect white people who are seen as the real innocent victims of an emerging endemic.

The specter of disease—and the overlapping mandates to fight it, protect ourselves from it, and follow protocols determined by it—looms over virtually every facet of our daily lives. In this sense, the alarm over “monkeypox” is moving in tandem with a battery of Covid-19-dictated restrictions, such as ethically dubious and racially motivated travel-bans. If this virus continues to spread, into white-dominated societies, there could be many Nushawn Williamses: Black men convicted of “reckless endangerment” because they are assumed to have known their status as a carrier of a life-threatening illness who would be alleged to use that knowledge like “a different kind of bullet.”

Singular acts cannot eradicate racism in a world that has subsisted on the demonization of Black people for centuries. Changing the name of “monkeypox” to something else will not eliminate the racist beliefs and practices that still determine which public health measures are funded and who is protected. At the same time, such a change in language will help draw attention to the entrenchment of racism within the predicates of public health policy making. Winnie Byanyima, head of the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS and UNAIDS, cited the panic over monkeypox to observe that racism is entrenched in our development institutions and that racism was created to justify slavery.

Old habits and beliefs die hard. For hundreds of years, white people whose wealth and comfort has relied on the enslavement of Black people required a whole pseudoscientific belief system in order to dehumanize them. If someone is not human—if they are more a monkey or an ape—then they cannot claim the consideration afforded to a biological equal.

The virus long known as “monkeypox” is dangerous for many reasons. One of the most insidious and enduring of these dangers is its tacit racism, which once more casts the original Black people who got the disease from monkeys as animalistic, simianized others, whose lives are simply not as valuable as those of real, white-skinned humans. A name is not everything, but it is something. We can at least hope that changing this one will register the long-overdue refusal to continue indulging the tropes of the garish and dehumanizing racism of the modern West—the real disease, in other words, that demolishes our collective humanity.

Rafia Zakaria is the author most recently of Against White Feminism (W.W. Norton, 2021). She is also a columnist for The Baffler and Dawn (Pakistan).