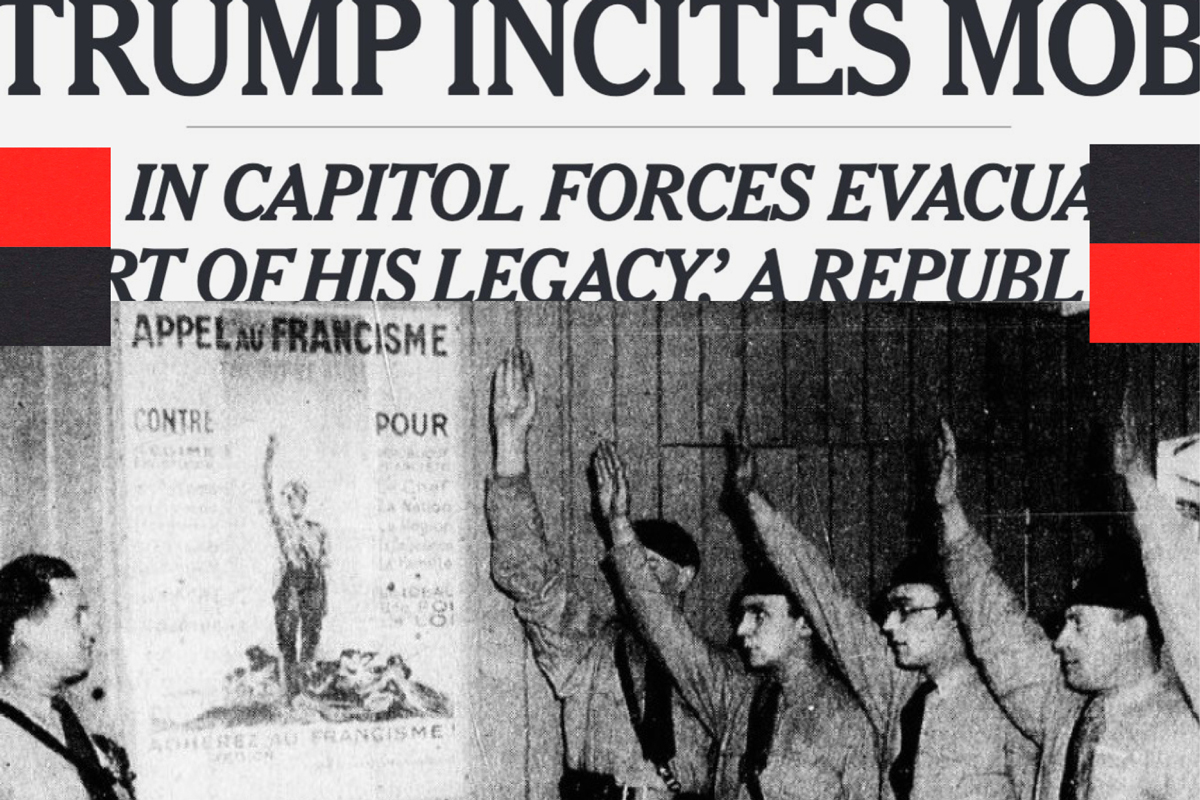

Over the weekend, the Texas Republican Party adopted a platform doubling down on far-right conspiracy theories asserting that the 2020 election was stolen from incumbent President Donald J. Trump. Right-wing political leaders in the Texas GOP thus formalized the adoption of the Big Lie that fueled the January 6 insurrection as a de facto litmus test for aspiring candidates for state and national office. More than that, though, the declaration that Joe Biden is not, in the party’s view, the legitimate president of the United States is part of a far more ambitious strategy aimed at undermining the legitimacy of a growing multiracial coalition committed to moving the state forward. How far the of the Texas Republic Party expect to extend this strategy is clearly signaled in the other extremist policy entries in the platform, which terms homosexuality “an abnormal lifestyle choice,” seeks to abolish public education, proposes mandatory classroom instruction in state public schools on “the humanity of the preborn child,” calls for the deregulation of gun ownership across the state, and demands the abolition of the federal income tax and the Federal Reserve.

Some political observers greeted news of the new platform as evidence that the Texas GOP had strayed beyond the pale of reasonable and respectable political opinion. In reality, though, the state’s extremist policy wish list is wholly in line with the hard right make-up of contemporary Republican politics—and a clear extension of Texas’s own tradition of deploying racial reaction and backlash as the basis for resurgent conservative rule. Another key demand in the platform was the formal revocation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act—a process that’s already well under way, as a practical matter, in many Texas districts.

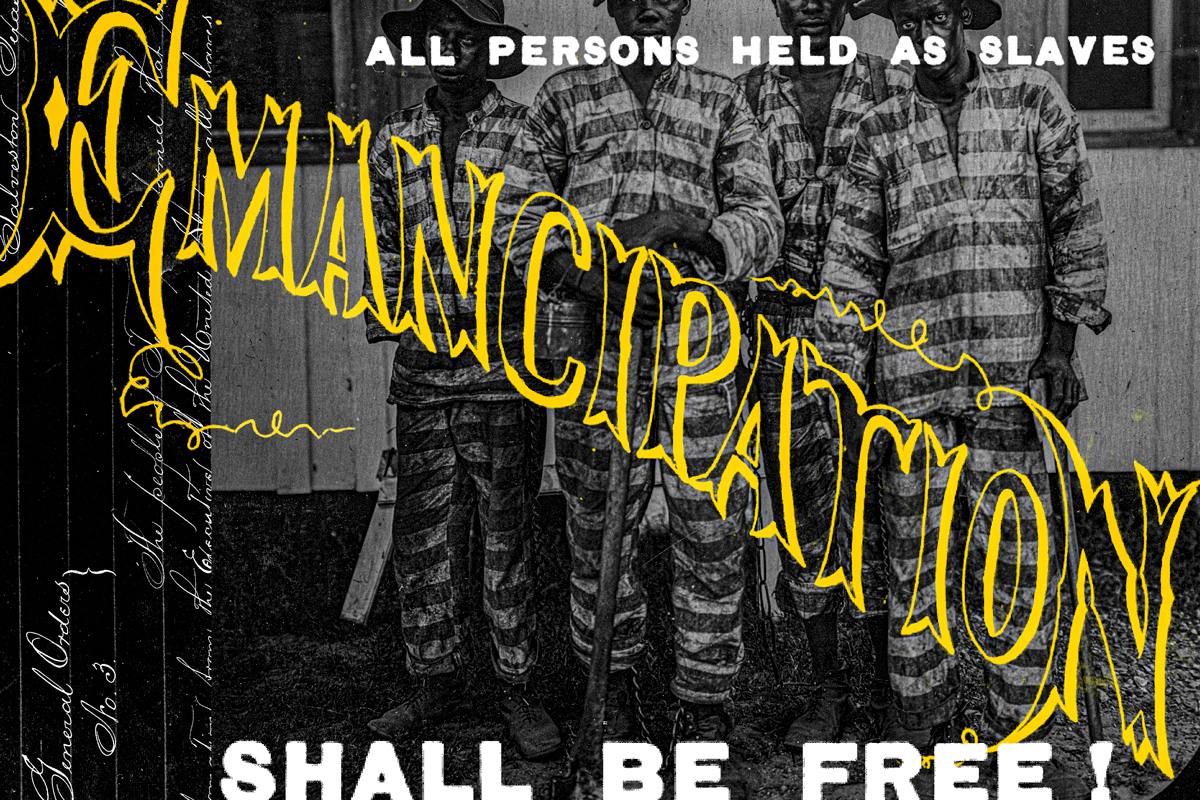

This, too, is largely business as usual in the Lone Star state. Denying Black enfranchisement and self-determination has been the story of racism in Texas since before the Union Army promulgated news of emancipation in Galveston, and launched the Black American commemoration of Juneteenth. With the opportunity to create a new state of possibility at the end of the Civil War, state leaders continued on the course that had launched Sam Houston’s white settlers’ republic in the first place: seeking to dispossess indigenous and Mexican communities of their birthright while denying freedom to enslaved Africans.

To see this point clearly, it’s crucial to highlight the racial dimensions of the Big Lie now at the core of the reactionary putsch in the state GOP: While the attack on the legitimacy of the Biden presidency may seem a tossed-off concession to the vast Trumpian cult of personality that’s enveloped the GOP, it signals a far deeper attack on Black and Latino voting rights. All the many bogus claims about voter fraud in the 2020 balloting focused on districts and precincts with sizeable African-American electorates—and fabricated tales of mass voter fraud on the part of undocumented immigrants. Just as the white settlers who controlled the state in the nineteenth century worked to marginalize and disfranchise Black, Native American and Mexican citizens, white nationalist leaders of the state Republican Party view the rise of multiracial organizing to build a functional democracy that works for all people as a clear threat to the governing edicts of white supremacy.

That’s why, for all the Texas right’s rhetorical commitment to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, the state party remains unyielding in its strict adherence to the original language of the United States and Texas constitutions. Slavery and the systemic dehumanization of Black people were built into these documents—and the modern course of Texas conservatism has remained steeped in this foundational dynamic, from the battles over school desegregation in the wake of the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision down through today’s rolling inquisition against critical race theory in Texas public schools.

The attack on the legitimacy of the Biden presidency signals a far deeper attack on Black and Latino voting rights.

Alleged signs of “growing” diversity within the Republican party in states like Texas don’t alter this structural state of affairs. Indeed, the new GOP platform makes a point of continuing to demonize critical race theory, even as it professes to support a “common American identity, which includes the contribution and assimilation of diverse racial and ethnic groups.” The notion of a “common American” identity plainly translates in this context as “white”—just as the cursory invocation of racial inclusion succumbs promptly to the mandate of “assimilation,” which in the Texan and American past alike means subordination to pre-existing racial hierarchies. The platform essentially says that the state GOP will limit opportunities for the advancement of non-white groups so as to ensure they will not infringe upon the alleged freedoms of the party’s white majority. The spirit of the entire platform, including the anti-CRT rhetoric used to enrage white parents, would limit advancement for Black and other people of color by virtue of prioritizing its view of Americanness through a white supremacist lens.

To help sanitize this agenda for public consumption, the state party leadership has been careful to provide cover for such regressive policy agendas by cultivating a surface appearance of diversity within its ranks. At the forefront of this initiative is rising GOP star and Black congressional candidate Wesley Hunt. He drew strong right-wing support in the Republican primary for the newly created 38th congressional district centered in the suburbs of Houston. While Hunt courts a more diverse electorate, he also echoes the party’s dishonest assault on CRT, and endorses hard-line anti-trans and anti-abortion sentiments. Not surprisingly, Hunt has won the endorsement of former President Trump, which makes him a shoo-in for the safely Republican district he’s seeking to represent.

Texas’s new GOP platform also includes language supporting a potential statewide referendum on secession in 2023—an especially mordant development over the Juneteenth holiday weekend. Of course, the Confederate outlook in Texas wasn’t extinguished overnight on June 19, 1865. Indeed, In between the words of the Union Army’s General Order No. 3 announcing emancipation of the state’s formerly enslaved population is a clear indication that emancipation would not mean equality in all matters: “The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages,” the order announced. “They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.”

This effort to preserve the existing limits on Black Texans’ geographic and economic mobility clearly helped set the stage for the Black codes created in 1866, which severely proscribed the rights of newly freed Black people. And forced labor continued after the issuance of General Order No. 3–just as it did after the ratification of the 13th Amendment.

As noted by the Library of Congress, many plantation owners refused to acknowledge the end of the Civil War or the validity of General Order No. 3—meaning that some Black people remained enslaved despite its illegality.

In the language of the order, freedom and equality are only defined in relation to Black citizens’ ability to work in, and remain at, their “homes”—places where newly freed Black people had been previously held as property. Overcoming their antebellum status as property did not render Black Americans anything close to the status of equals in the eyes of their white neighbors or the law.

In “Racial Violence and Reconstruction Politics in Texas, 1867-1868,” Gregg Cantrell wrote that Texas stood out in the former Confederacy “as one of the strongholds of Southern intransigence.” An estimated 408 Freedmen were murdered between 1865 and the first half of 1868. Cantrell noted that while some of the violence may have been politically motivated, the widespread hatred of Black people in the state overrode other rationales for white vigilantism.

The grim history of post-emancipation violence points up the continued brutality and oppression that sustained white supremacy into the modern era. Now, as then, the purpose of such violence is to enshrine white control and domination at all costs—another throughline that connects the Texas GOP’s absolutist stance on individual gun ownership with its expansive white nationalist agenda.

And here, too, the surface appearance of diversity in leadership ranks does nothing to alter the underlying political appeals to untrammeled white impunity, which has lately graduated from dog- whistle rhetoric to outright clarion calls. Black Republicans such as Hunt and former Texas GOP Chairman Alan West harmoniously share their political platform alongside people such as Rep. Chip Roy, who carelessly alluded to lynchings as “justice” during a hearing aimed at addressing anti-Asian violence. After facing criticism for his bigoted incitements, Roy doubled down on the rhetoric of racial terror, saying that bad guys deserved it.

It’s again important to attend to the political traditions that such talk keys into. For decades on end in Texas and the rest of the country, free Blacks and Latinos were the “bad guys” in the high-paranoid reveries of influential white political leaders on the right who imagined themselves besieged by demographic and ideological threats on all sides. The open tolerance of such talk has always been a license to preserve a racist status quo: white supremacist rhetoric does not hinge on announcing specific intents, but inheres within the broader frameworks of racialized threat that continue to shape policy and govern communities.

The hard truth, today as in 1865, is that people benefit from their proximity to white supremacist power.

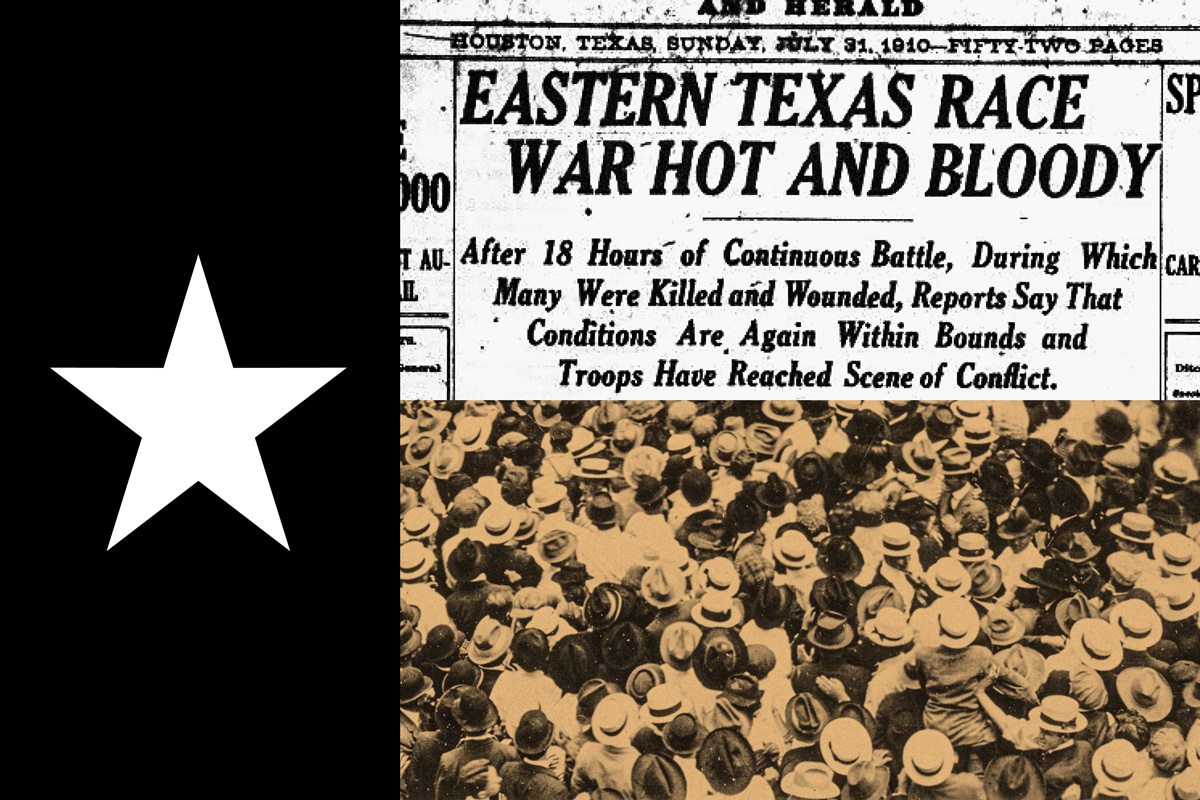

Under this brief of unchallenged racial impunity, armed white mobs and vigilante law enforcement snatched away Black lives at will, often in overt public collusion. Incidents such as Texas’s 1910 Slocum Massacre displaced Black citizens who escaped mob violence by forfeiting property and land holdings to racist whites.

In many ways, these campaigns of violence against Black people by southern racists were enabled by influential whites in national politics seeking to downplay or dismiss the realities of racial terror—as when Georgia-born President Woodrow Wilson sought to wish away the crucible of the Civil War as a “quarrel forgotten.” In the same vein, as the Zinn Education Project has reported, Black religious leaders wrote to President William Howard Taft asking for help after the Slocum Massacre. But Taft and his allies made it clear that no such federal aid–let alone anything like justice or reparations for the massacre’s victims—would be forthcoming.

Today, it’s all too easy for Democrats and “good white people” to point fingers and shake their heads at Texas as a racist state, but such rhetorical self-distancing works to perpetuate the conditions that allowed the Texas right to veer into such extreme territory—namely, the unwillingness to directly challenge white supremacy head-on. The hard truth, today as in 1865, is that people benefit from their proximity to white supremacist power and would rather maintain the status quo over the uncertainty of supporting efforts to build multiracial political power.

With Texas’s all-too-legible historic investment in the disenfranchisement of Black people and the dispossession of indigenous communities, the Texas right’s militant commitment to an originalist interpretation of Texas’s constitutional order sustains and extends an undemocratic legacy of brutality and oppression.

And the brittleness and rigidity of this commitment bespeaks a genuine fear of multiracial democracy that’s important to underline in the struggles ahead. Texas Republicans clearly regard Black liberation and equity, coupled with multiracial organizing across historic ethnic, racial and religious lines, as an existential threat, one that mandates the renewed subjugation of communities of color. As Texas Republicans and their acolytes fight to retain power in a white supremacist order, groups like the the Texas Organizing Project (TOP) are mounting a powerful counter-organizing effort, seeking to forge new coalitions to sustain and defend multiracial democracy.

“The only path to a progressive Texas—a true Texas for all—is through authentic engagement in Black communities,” TOP Co-Executive Director Briann Brown said in a statement commemorating the Juneteenth holiday. “On this day, we recommit ourselves to dismantling the structures designed to deny Black people their freedoms and instead create systems and conditions in which we can thrive because Black lives do matter. We do this by organizing and building power in the communities in which we reside.”

As the new GOP platform makes clear, these crucial grassroots mobilizations have to meet a whole battery of hard-right enclosures on equality and autonomy that always translate into racial marginalization. Texas is already notoriously home to one of the two most restrictive anti-abortion laws in the country, complete with bounty hunter-style provisions offering cash rewards to citizens reporting on people getting abortions. The criminalization of bodily autonomy disproportionately harms Black and Latinos, who face acute structural and economic obstacles to abortion access—which in Texas will mean they must also reckon with unnecessary and life-altering interactions with the criminal legal system. Since it relies on individual reports, the Texas abortion bounty-hunter law breeds racial discrimination, given the stereotyped image criminality that widely stigmatizes Black Americans and other people of color.

“These actualities . . . sadly show us just how much farther we have to go to end white supremacy and the lingering, systemic harms of enslavement in this country,” said TOP Board Member Kevin LeMelle. “The fight to fully realize the promise of Juneteenth continues—a fight I will not retire from until we, as Black Americans, are truly free.”

Anoa Changa is a southern-based movement journalist and editor at NewsOne.