Diary of a Targeted Teacher

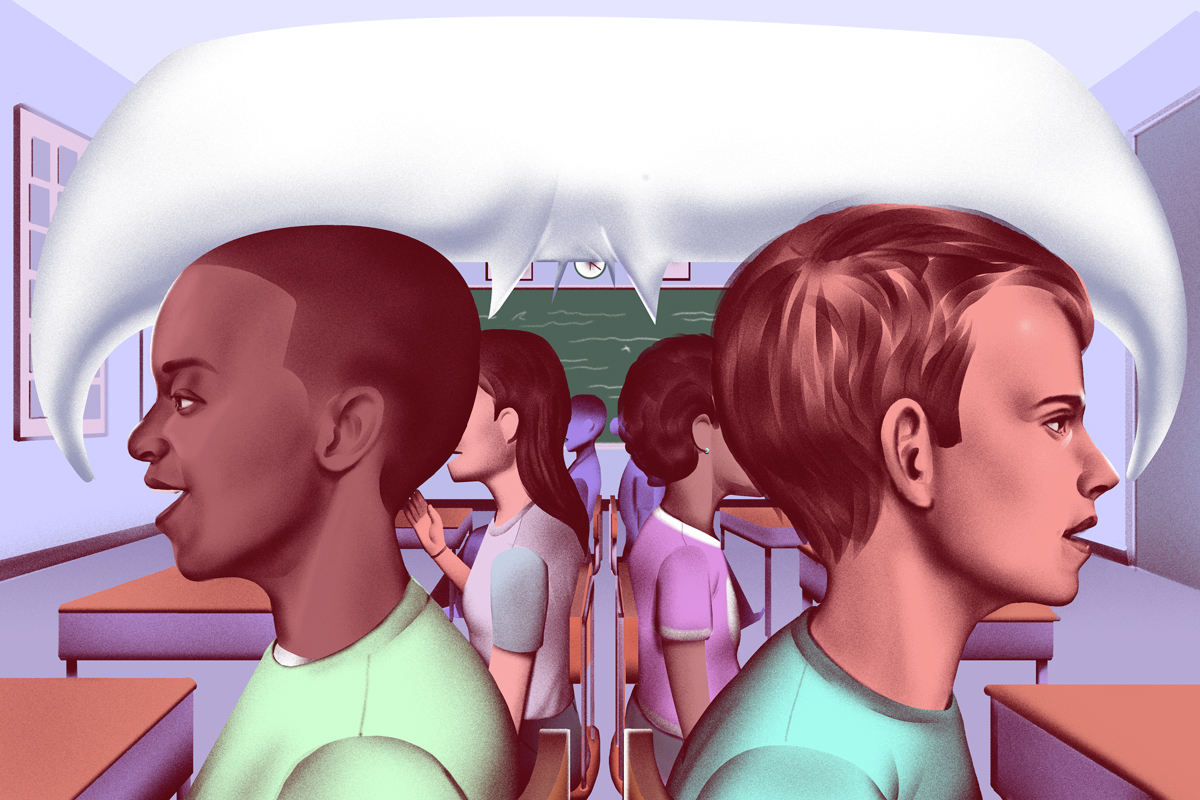

I often ask my white students what it means to be white. And just as often, they have no answer.

“I’ve never really thought about what it’s like to be white,” one student says.

“There’s never been a time in my life when I was conscious about my skin color or felt discriminated against.”

“Nobody’s ever asked me before,” says another.

“It doesn’t really mean anything to me,” says another.

They say this casually, yet such statements are stunning. Part of the curse of American racism is this deep element of not-knowing within whiteness. As white men and women, racism was ours to invent, cultivate and systematize, and we did so with a wicked magic that also allowed us to forget, to remain asleep, to not-know. We suffer from a damning amnesia, an act of willed forgetting that often forms the essence of what it means to be white.

“I’ve mostly lived in all-white neighborhoods and gone to all-white schools, so I don’t really have a racial story,” another white student says.

“I was born in a white family, lived in white neighborhoods. Race is never talked about. It just doesn’t really affect us,” says another.

“I’ve always gone to private schools with other white kids,” says another, “so race was never a problem.”

As white men and women, racism was ours to invent, cultivate and systematize, and we did so with a wicked magic that also allowed us to forget, to remain asleep, to not-know.

Never … a … problem.

Doesn’t … affect … us.

This, too, is part of whiteness: the belief that to be white is to be non-racial. That to live white in America somehow elevates us out of a racial experience. We think we are immune and exempt. Race is therefore about being Black or brown, not white.

Theoretically, my white students could continue such a trajectory forever, arranging their lives so as to avoid any sort of meaningful inquiry, encounter, or examination around race and whiteness. School, college, careers, church, neighborhoods—all of them can be experiences in which a modern form of segregation erases race. In fact, as 17-year olds, they are already finding—however unwittingly—that the momentum in their lives is steering them in such directions. Our school does little to interrupt this.

Never … a … problem.

Doesn’t … affect … us.

I watch Black and brown students in the room as they hear this; for them, such statements reflect experiences that are unheard of, the most fantastical of all fantasies, like traveling to the moon.

“I just want to know for one day,” one Black student responds, “what is it like to be white? To walk around like this? To never have to worry?”

Another Black student speaks up:

“Here, the students are white, teachers are white, those who work on the campus as administrators are white. And, most of the families are white,” he begins. “But, the janitorial staff? They’re mostly Black. A few students here and there are Black. Our teachers aren’t Black. Our administrators aren’t Black. Nothing against white people, but when I can’t find 20 people of my own color compared to 1,000 white faces staring at me every fucking day, it really starts to get to you.”

If whiteness can be synonymous with not-knowing, whiteness therefore involves delusion. Schools often operate on the whiteness of not-knowing, which makes them schools of delusion. A school may win state titles or graduate scholars, yet remain racially illiterate.

I don’t shame or guilt these white students. In fact, I love them. I’m grateful for their honesty. I even see my former self in them. I, too, lived for far too long with whiteness that had no wisdom, understanding or responsibility bound up with it. So I keep asking.

Often we keep looking.

Schools often operate on the whiteness of not-knowing, which makes them schools of delusion.

And often, here is what we find:

Sadness, guilt, an emptiness, confusion, regret, heartache, superficiality, ignorance. In my experience, one reason why white America often misappropriates other cultures is because such cultures have meaning, depth, resiliency, and structured and shared bonds—whereas whiteness often does not.

Yet we also can experience a genuine hunger to be part of the solution. To fix the broken things. To sever the generational racism in our own family tree. To see clearly, love better, build relationships and community. Many white students ache for such things. (And this is all to say nothing, of course, of how Black and brown students can benefit from a public setting where they are seen and heard, and have their experiences validated, on a sustained basis; we’ll explore that facet of teaching race at length in future columns.)

So if we can give white students spaces where they encounter one another in honest, disarming and challenging ways, then the possibilities for relationships, truth telling, transformation and healing occur.

“No other class has affected me more than this one,” a white student says.

“I came into this class unaware of my own ignorance, which can be part of being white. Sure, I could have stayed on this path, and it would have been easier, but it is not the right path,” another says.

“I’d never thought about or questioned race before. Now, my vision has truly changed. It’s remarkable what can happen when people have uncomfortable conversations with each other,” another observes.

“I have been torn down, put back together again in ways that help me grow,” says another.

I do not say this to boast, but rather to report: discussing race reduces delusion, and opens walled-off minds and closed-up hearts. White students often begin to see what they once did not. And they are so thankful for that.

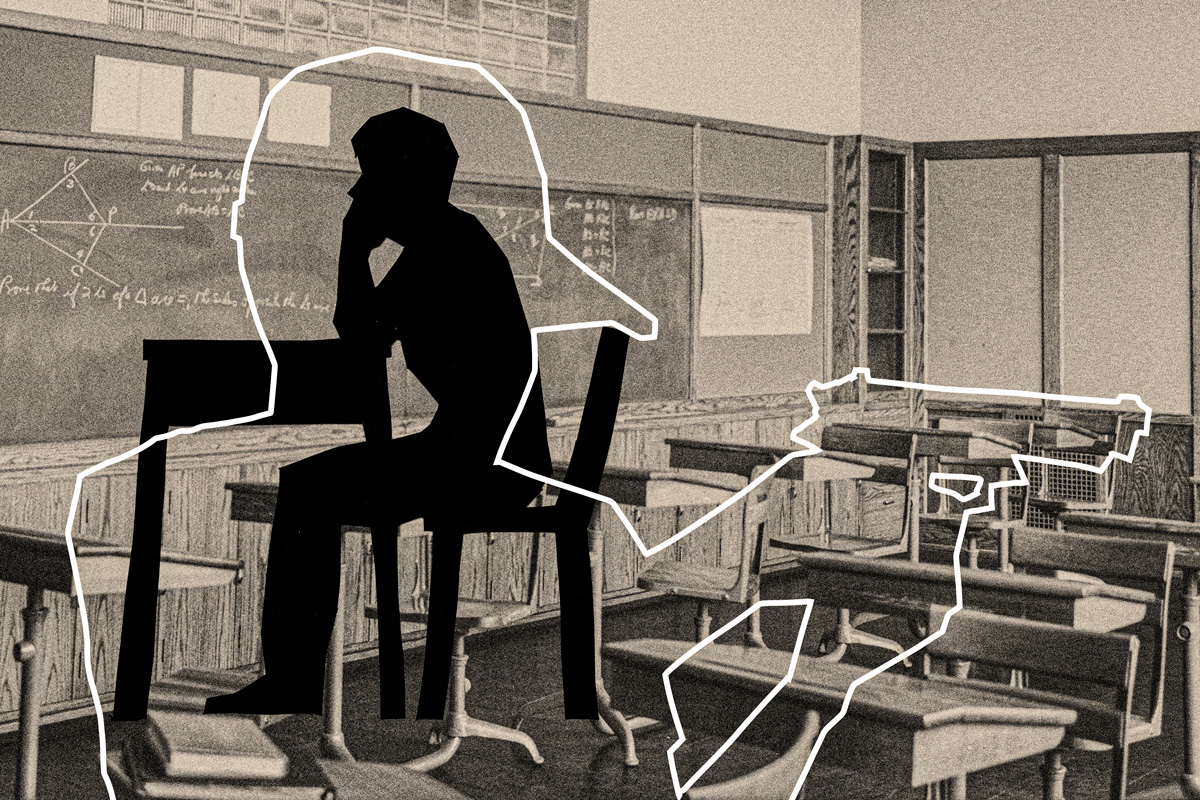

Yet in most places, such teaching remains illegal.

Willie Randall is the pseudonym for an American educator who’s taught race and racial theory at multiple schools in multiple states.