Diary of a Targeted Teacher

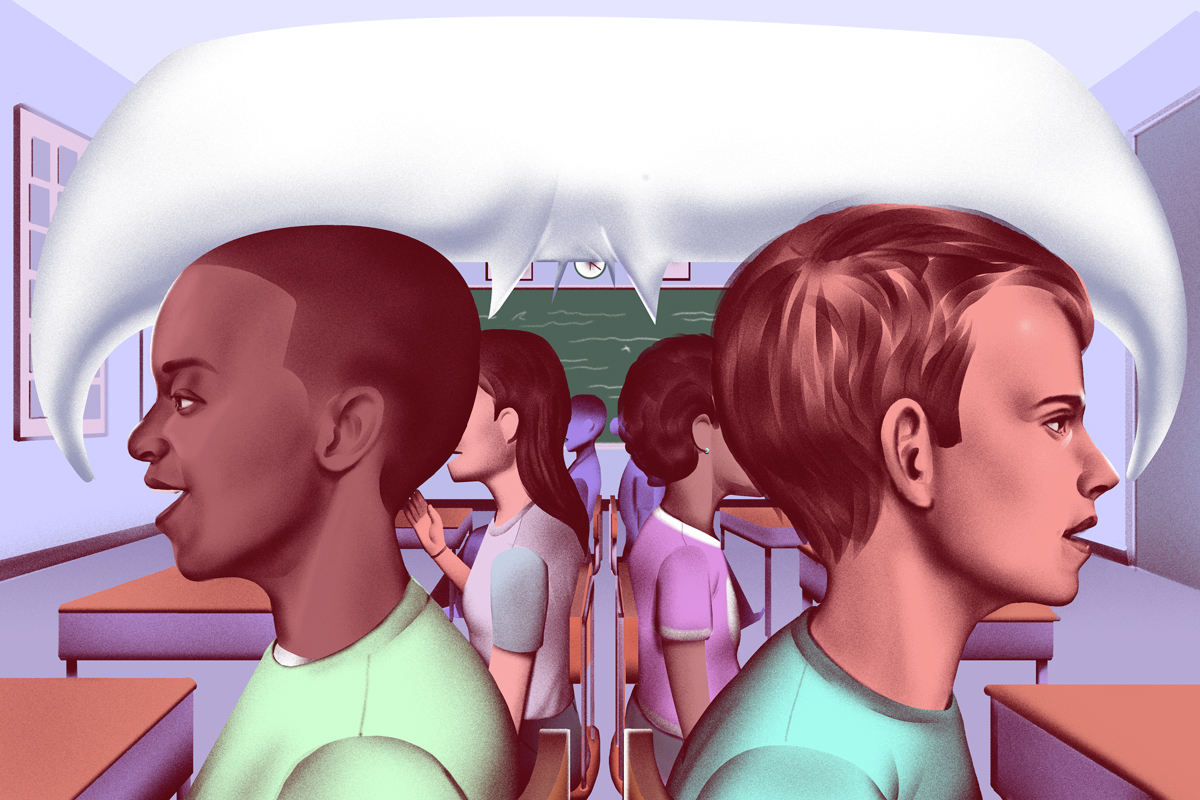

What does it mean to teach race in a classroom? Many in America believe such work is akin to indoctrination. In my experience, nothing could be further from the truth.

To teach race, I ask questions. I craft these inquiries to be a gentle knock on the heart’s door. Indoctrination bullies and backs us in corners, funneling students toward rigidity and orthodoxy; questions disarm and invite, throwing open all windows and doors to reveal many paths to knowledge.

But before posing questions, I do two things: build trust and remove fear. Nothing sunders or damages the spirit of a classroom more than fear. As their teacher, I do not agitate, insult, demean or embarrass my students; through my presence and actions, I communicate respect, love and trust. So, when the questions come, students know I am in their corner, on their side, with them every step.

We start with two.

What race are you?

How do you know?

My students have been asked ten thousand questions in their academic lives, but never these. They freeze, squirm, chuckle. A few lean forward, as if hearing something for the first time.

I ask again.

What … race … are … you?

“I’m white,” one student says.

How do you know?

More chuckling; isn’t it obvious? Here, trust becomes my collateral; they’re willing to follow that trail, however ridiculous the first steps may appear.

“I’m just white,” he answers.

Yes. I know it sounds silly, but trust me. How do you know you’re white?

He pauses. He looks at his arm. “My skin,” he says. “I look in the mirror.”

Thank you, I say. Then: Are there any other white people in the room?

More laughter. The room is nearly all white.

Race takes the unfathomable diversity of the pigmentry of the human skin and reduces it into the most boring and narrow of boxes.

How do you know you’re white?

“Our skin. We look white,” they say.

Are there other reasons?

A pause.

“Our history. We come from places with white people. You know, our ancestors,” another says.

They tick off locations: England, Scotland, Germany, all European countries. (Later, a Black student, who’d just finished an ancestry project for history class, tells her classmates she’s unable track her ancestors; as the descendent of slaves, her history has been erased.)

“I’ve always been told I’m white,” one student volunteers.

Outstanding answer. Are there other races in the room besides white?

“I’m Black.”

“I’m Pakistani.”

“I’m Chinese.”

“I’m Hispanic.”

How do you know?

Same answers emerge. As they talk, I summarize on the board:

- Skin color.

- Location/ancestry.

- That’s what we were told.

It’s a flimsy house, this thing we call race. When we look carefully, we see it’s made up of sand and shadows; there’s nothing of substance here. Yet we have built empires upon its foundations, sold families into bondage, denied futures and normalized nightmares. All based on nothing.

Skin color? There’s no such thing as white. I’m not white, and neither is anyone else. White people may be pale or light-skinned, but absolutely and utterly white? Or Black? Race takes the unfathomable diversity of the pigmentry of the human skin and reduces it into the most boring and narrow of boxes. Standing before my students, I roll up my sleeve: how much darker before I’m Black? We reference celebrities or well-known Americans who are dark-skinned Asians. Are they Black? One Black student holds out her bare arm next to an Asian classmate, who’s darker, but does not identify as Black. The Black student is lighter, but also Blacker.

Racial terminology is inconsistent. You may identify as Chinese, yet the person next to you calls herself white. One is a location; the other, a color. Does race refer mostly to geography? Or skin tone? All those places you mentioned—England, Germany, Italy—are locations, not colors. To define yourself by the heritage, history, culture and location of your ancestors is not race. We already have a name for that. It’s ethnicity.

Look, I’m not asking you to be stupid or naive, I tell them. Yes, people look different. Fly in a jet plane to Taiwan then Siberia then Burkina Faso then Honolulu, and in each place, people generally will appear very different. Color exists in obvious and beautiful ways. But that isn’t race. It’s years of evolution. We mistake physical differences and ethnicity for this thing called race, which is an inherent and structural act of comparison originating in greed. Race will always lead to domination and hierarchies because that is what it is meant to create.

“Race is the child of racism, not the father,” Ta-Nehisi Coates writes. “And the process of naming ‘the people’ has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy.”

It’s an invention, I tell them. A scientific fiction. It’s bogus. I’m not white. I am a light-pale-skinned American whose people came from England. There is no “white” gene in me; scientists can’t look at my DNA and find a genetic strand of whiteness.

We mistake physical differences and ethnicity for this thing called race, which is an inherent and structural act of comparison originating in greed.

“The mainstream belief among scientists is that race is a social construct without biological meaning,” declares Scientific American.

“Race is a biological myth,” Dr. Alan Goodman, professor of biological anthropology at Hampshire College, explains to PBS. These five words require a tremendous paradigm shift. “It’s like seeing what it must have been like to understand that the world isn’t flat.”

At this point, it’s like the red-pill-blue-pill scene in The Matrix. The rabbithole is nigh. I’m sensitive to what’s happening: everybody okay? Is this confusing? Difficult? Let’s breathe for a moment and get our bearings.

They look at me, these 17-year-olds conditioned so fully and thoroughly to believe in race. What the hell is this guy talking about? Of course, I’m white. Of course, the world is flat.

One more step to go. We look at statistics and graphs. Black-to-white inmate populations. Black-to-white poverty ratios. Black-to-white household savings and home ownership rates. Here in our city, whites earn twice as much as Black families. This biological illusion is also a social reality. This genetic fiction also killed, enslaved, raped, redlined, mutilated and segregated. Nobody is telling you not to see color. Nobody is saying there’s no social difference between Black and white and brown. It isn’t a small world, after all.

I’m asking them to hold two different truths in their hands: race is both unreal and nightmarishly real. Yet I teach under no assumptions that this lesson will stick. These students are operating under nearly two decades of life woven into the gears of the machine of American conditioning some 400 years old. Two little questions seem no match for this.

Yet what else can I do? Can education dismantle such a leviathan? Can anything?

These are the questions I cannot seem to face or answer.

Willie Randall is the pseudonym for an American educator who’s taught race and racial theory at multiple schools in multiple states.