The twenty-sixth Academy Awards ceremony, broadcast in 1954, was a landmark event in two ways: it registered a new era of public recognition for America’s commercial film industry, and the end of a significant period of Hollywood history. It was the second-ever Oscars ceremony to be televised, and the first produced for maximum impact on television. The ceremony also marked the retirement of Honorary Oscar winner Joseph Breen, the longtime head of Hollywood’s Production Code Administration.

The Motion Picture Production Code, widely known as the Hays Code, was a set of “self-regulation” or “self-censorship” practices that ruled Hollywood sets from 1934 to 1968, when Hollywood introduced today’s familiar MPAA ratings. The Code, which was heavily influenced by Catholic ideas of public morality and co-written by a Jesuit priest, sought to inscribe “traditional” values into American cinema by upholding a set of “general principles” that, according to the 1930 version, prized “the moral importance of entertainment” and operated under the assumption that “wrong entertainment lowers the whole living condition and moral ideals of a race.” Some ideals included the veneration of women and the “sanctity of marriage.”

The Code’s second part, its “working principles,” was an itemized list of content it would not allow. It banned films that contained depictions where “evil is made to appear attractive, and good is made to appear unattractive.” Among many things, the Hays code banned portrayals of: sex; homosexuality; profanity; the critique of any religion; “white slavery”; and scatological humor. Although the Code’s strictures were clearly defined, some of the wording was incredibly vague. For instance, the listing forbids obscenity “in word, gesture, reference, song, joke, or by suggestion (even when likely to be understood only by part of the audience).” Of course, the Code’s core notions of “right” and “wrong” entertainment, together with its central mission of divining a mass audience’s sensitivity to suggestive material, were subject to wildly divergent interpretations. Yet censors, like nature, abhor a vacuum, and so Breen and his colleagues at the Production Code Administration accrued great power to define and enforce ironclad notions of how American taste should operate—particularly in the ever-charged realm of racial justice. For instance, though Breen’s office discouraged “daily usage” slurs against Black and Japanese Americans in Hollywood fare, it forbade mention of interracial romantic relationships, known then as “miscegenation.”

No wonder, then, that a Variety obituary published in 1965 memorialized Breen as “the most powerful censor of modern times,” and claimed that “more than any single individual, he shaped the moral stature of the American motion picture.” Thomas Doherty—the author of the 2007 Breen biography Hollywood’s Censor—recounts that in 1936, Liberty magazine described him as someone who “probably has more influence in standardizing world thinking than Mussolini, Hitler, and Stalin…possibly more than the Pope.” With all of that reach, Breen’s departure from the PCA heralded a monumental shift in Hollywood culture, which the TV-savvy Oscars producers set out to document. This melancholy changing of the guard was reflected in the somewhat sanguine energy of the event.

For Breen’s walk-on music, the orchestra played western classic “Don’t Fence Me In”—a symphonic flourish that either was a sardonic callout to the cramped mood of Code-era production lots, or possibly a still more nuanced acknowledgment of how his sensibility gave creators more space to make work inside the confines of the Code. Maybe it was a nod to the fact that, as a newly retired man, Breen was now finally free from all of that.

This Sunday’s Academy Awards ceremony, festooned as usual with ball gowns, tuxedos, and glittering golden statuettes, will bear only a passing resemblance to its 1954 precursor. There are, of course, some parallels: there will still be lots of self-congratulation on display. There will be tributes to the nominated films, insider jokes about Hollywood culture, references to decades-old moments from previous Oscars ceremonies, nods to current gossip, and the inevitable awestruck refrains about the “magic of the movies.” There will be exhortations to praise the nominated films for their dazzling craftwork as well as their social impact. This is where it’s easy to see how very different things are now. This year, the films up for Best Picture Oscars cover, among other themes, gay characters and queer sexuality (The Power of the Dog), climate change (Don’t Look Up), violence aimed at Catholics (Belfast), and feature Black protagonists (King Richard). Almost all incorporate sex scenes.

Yet unquiet shade of Joseph Breen will not be far offstage at this year’s Oscar festivities. Yes, American movies are far removed from the restrictions of Hollywood’s Production Code era—but over the past year of overheated culture warfare, there’s been a prominent resurgence of the rhetoric that enabled the Code’s thirty-four year run. The Oscars’ celebration of movies and their power contrasts with the confusing ways in which the arts both track and diverge from the dominant streams of cultural and political discourse. Now, absent a formal censor, the moral code of the medium is patrolled by a new sentinel: the Republican Party and its lobbying body.

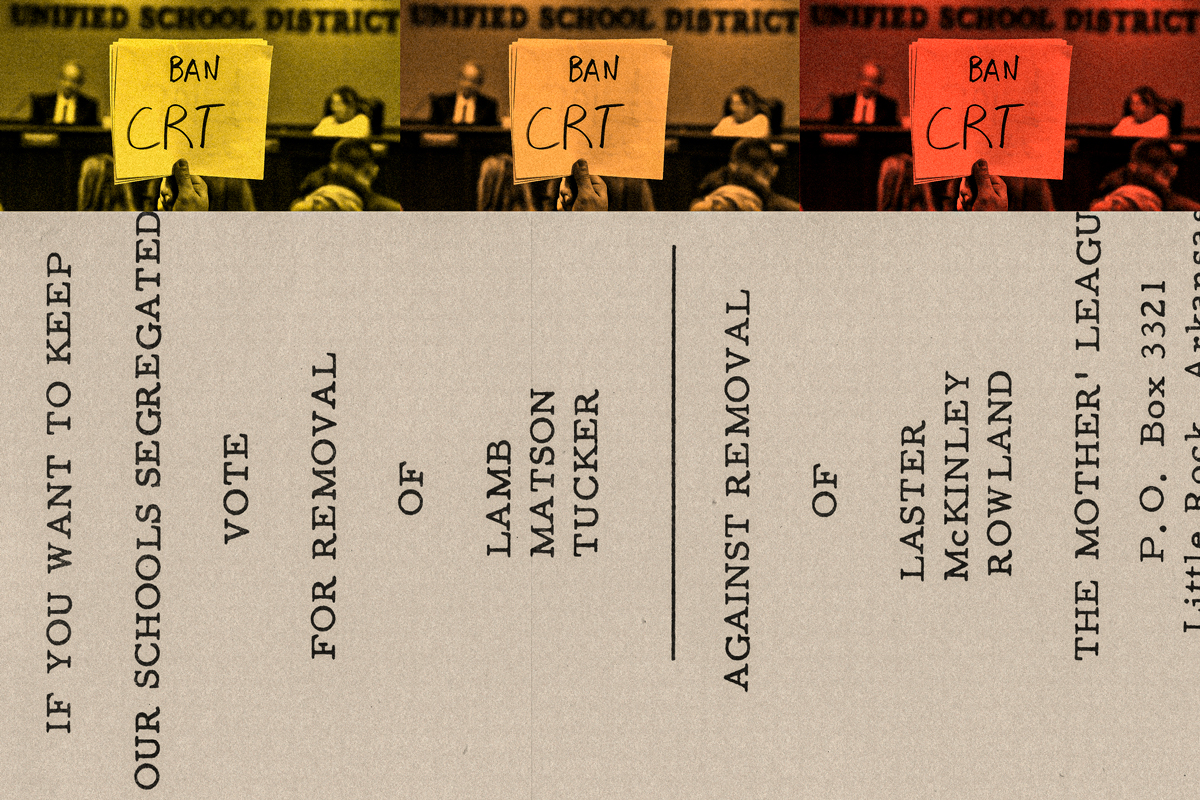

Increasingly, conservatives use critical race theory to frame conversations about restricting the arts, including movies. Critical race theory, broadly defined, is an umbrella term for a legal and academic framework arguing that race is a social construct, one that is upheld throughout major structures of American society. CRT scholars hold that racism is systemic and pervasive, and takes structural changes to eradicate. Critical race theory doesn’t blame white people for the sins of their ancestors, nor does it teach them that they are inherently bad. It does not emphasize individual expressions of racism, instead turning attention toward ways to address structural bias and inequalities.

These inconvenient truths have played no part in the last year’s great rolling moral panic over the alleged un-American attitudes and agendas that lurk within the CRT movement. In 2021, Republican lawmakers took steps to eradicate the teaching of critical race theory in federally funded schools. In May of last year, Republican Congress members, led by Rep. Burgess Owens of Utah, introduced a bill banning critical race theory as well as a resolution against it. Republican Study Committee Chair Rep. Jim Banks of Indiana argued that the framework taught “students to be ashamed of our country.” Other supporters of the bill said “Critical Race Theory aims to indoctrinate Americans into believing our nation is inherently evil,” dubbing it “anti-American revisionist history,” an attempt to “rewrite history through the lens of wokeness,” and “a warped ideology that seeks to divide Americans and relitigate the sins of the past by pinning White Americans against Black Americans.” The politicians frequently used the term “divisive”—a political buzzword that manages to be both incendiary and utterly banal—to describe both the motivations of their left-wing colleagues and critical race theory’s alleged impact. Republican-led legislatures in several states passed or proposed bills banning CRT education in 2021. On the campaign trail in October 2021, Republican Glenn Youngkin, who won Virginia’s governor’s race a month later, said, “What we won’t do is teach our children to view everything through the lens of race,” and vowed to ban critical race theory on his first day in office. In January, Florida’s senate advanced a bill to ban lessons that make white students feel “discomfort,” although it was “indefinitely postponed and withdrawn from consideration” on March 12.

Absent a formal censor, the moral code of the movie industry is patrolled by a new sentinel: the Republican Party and its lobbying body.

The irony of the hubbub surrounding this discourse is that just as critical race theory supposes, rightly, that racism is endemic in American institutions, these lawmakers and other foes of CRT have turned what should be a basic, non-controversial statement of fact into a bogeyman who draws unmistakable and dramatic attention to the pervasiveness of structural racism. Conservatives have started to see CRT everywhere. This means a far more serious division has taken place in our racial politics. There are two narratives in play: one that acknowledges the persistence of abiding structural inequality and presses for a thoughtful and strategic path forward to dismantle it, and the other in which strawmen undermine American progress by obsessing over race. In the bad-faith portrayals of the Trumpian right, critical race theory is a corrupting force, a rhizomatic villain responsible for destroying American souls, calling to mind an ideological Power Ranger formed of “woke” constituent parts.

Crucially, critical race theory is positioned as a tentacular menace that disguises itself in other ideas. As Patti Hidalgo Menders, president of Virginia’s Loudoun County Republican Women’s Club told the Guardian in November, “They may not call it critical race theory, but they’re calling it equity, diversity, inclusion. They use culturally responsive training for their teachers. It is fundamentally CRT.” In a piece called “Critical Race Theory’s New Disguise” published in October, Ayaan Hirsi Ali wrote of CRT’s “remarkable ability to shape-shift into whatever form its advocates choose.” The Heritage Foundation, a right-wing think tank, put together a guide to identify CRT with the tagline “Knowing critical race theory when you see it and fighting it when you can”; the guide asks readers to “become a whistleblower.” In order to vilify critical race theory, right-wingers have repackaged the tactics used to identify conservative dog-whistles, and incentivize spying in states where abortion has been banned.

During “The New Intolerance: Critical Race Theory and Its Grip on America,” a panel discussion hosted by The Heritage Foundation this January, moderator Angela Sailor cautioned, “Critical race theory is the complete rejection of the best ideas of the American founding. This is some dangerous, dangerous philosophical poisoning in the bloodstream.” Another panelist, Christopher Rufo—the Manhattan Institute fellow who launched the anti-CRT moral panic in 2020—warned that proponents of critical race theory were attempting to “inject” academic tenets “into the bloodstream of every institution, from kindergarten to the federal government.” The invocation of blood poisoning could have been an offhand metaphor, but it tracks with the kind of Jim Crow-era figurative language used in legal contexts to reify racial difference—including the “one-drop rule,” anti-miscegenation laws, and notions of “racial integrity”—a phenomenon Daniel J. Sharfstein detailed in a 2003 article for the Yale Law Review. Again, the irony here is altogether crushing: if these panelists had read some of the work they scapegoat, they might have avoided the racist implications of such language.

In a recent essay, Washington Post film critic Ann Hornaday explored the ways that emerging “don’t say gay” and anti-critical race theory laws would limit the accessibility of films like 12 Years a Slave, Selma, Harriet, Judas and the Black Messiah, and The Hate U Give in classrooms. These films all have associated study guides, and are used in schools around the country as teaching tools. Now, due to the capacious and vague strictures of this new cohort of anti-CRT laws, there’s a chance these movies wouldn’t be allowed in schools. “Of course, teachers are facing more pressing issues than movies right now, between the dropping of mask mandates and addressing learning loss during the pandemic,” Hornaday writes. “But they will increasingly be weighing more carefully than ever what books to assign, what ideas to address in their lectures and—perhaps most crucially for generations of students steeped in visual language—what movies to show.” In this regime of repressed speech, Republican politicians, conservative thought leaders, and demagogues like Donald Trump become twenty-first-century versions of Joseph Breen, gatekeeping films based on their personal taste.

Film indeed supplies a powerful idiom for understanding how the CRT panic operates in our mass politics. In conservatives’ rendering of critical race theory, the framework presents the philosophical villain as the sort of insidious bogeyman that has shown up repeatedly and most notably, not only in the imagery of scifi and horror movies, but also in the propaganda films and stereotypical representations of American cinema’s “classical” era. This worldview posits that things that are “fundamentally” critical race theory, to echo Patti Hidalgo Menders, are masked by protective camouflage, which mandates their exposure by whistleblowers. The “enemy within” framing of anti-CRT discourse also revives the familiar McCarthyite figure of the sinister Communist subversive hiding in plain sight, undermining American democracy by means of subterfuge. And the right-wing depiction of such figures administering CRT injections into the country’s “bloodstream” harks back to the sneering, sliding, hiding evil Black man waiting in the bushes of D.W. Griffith’s infamous 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation, attempting to ensnare innocent white women passersby.

These racialized tropes of political fear have long figured prominently in our debates over the acceptable range of expression in American culture. In his 2007 article “Black and White and Banned All Over: Race, Censorship and Obscenity in Postwar Memphis,” published in the Journal of Social History, scholar Whitney Strub details the ways that “race shaped censorship and local definitions of obscenity in Memphis.” He also charts the powerful municipal forces that shaped the city’s public entertainment in the early twentieth century:

A Board of Censors, with power to regulate all motion pictures, plays, and other public exhibitions, was established in 1911 but was not formally codified until a decade later. The Board acted relatively infrequently, though it censored a 1914 film of Uncle Tom’s Cabin on the grounds that it might cause a racial disturbance. That same year, Memphis banned a play based on Klan-adoring novelist Thomas Dixon’s The Leopard’s Spots in response to black protestors who appealed directly to [Memphis mayor E.H. Crump].”

Strub also notes that Memphis banned Vincente Minelli’s all-Black musical Cabin in the Sky when it premiered in 1943:

When Cabin in the Sky, a frivolous musical film with an all-black cast, opened in Memphis that year, city leaders suddenly identified cinema as a potentially destabilizing force that needed to be controlled. A resolution, attributed to “serious public disorders and race riots,” was passed banning the exhibition of films with all-black casts or with “negro actors performing in roles not depicting the ordinary roles played by negro citizens” from being screened for white or mixed audiences.

Strub’s examples are fascinating. It’s notable that in some Southern cities like Memphis, pressure from both Black and white communities could result in censorship. It’s surprising that an outcry from Black citizens meant anything in the South in 1914, but history is comprised of complicated stories. Part of the reason why critical race theory is unfairly maligned is that its structural reasoning stresses facts that present a portrait of America’s complex trajectory. Indeed, Strub argues that “the history of Memphis remains incomprehensible unless seen through the lens of race” and still presents a nuanced look at a compelling, likely underreported regional history of American censorship, in which city administrators, community activism, and oppressive policies all had a dynamic role to play.

Over time, regional battles over racial expression in film, like those in Memphis, gave way to more free-floating moral panics—chiefly over the irrational responses imputed to Black audiences—in the post-civil rights era. At the end of the Reagan years, a pair of high-profile films tackling racial subjects, Dennis Hopper’s Colors (1988) and Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989), were the subject of pitched discourse about riot incitement, artistic responsibility, and historical revisionism.

In 1988, a different red-blue conflict fueled the polarized impressions of race and identity in America: the Crips versus the Bloods. By the late 1980s, the dissemination of crack cocaine into Black communities across the country and the consequent intensification of gang violence were stoking new anti-Black moral panics. It was in the throes of this alarmist climate that Colors premiered. Colors concerns the drug-busting efforts of two LAPD officers played by Sean Penn and Robert Duvall, who have been assigned to the department’s gang violence task force. The movie is remembered mostly as a Sean Penn vehicle (and a footnote in a Vice News story about the expansion of Crips and Bloods into Honduras) though it was incredibly controversial when it was first released.

The “enemy within” framing of anti-CRT discourse revives the familiar McCarthyite figure of the sinister Communist subversive hiding in plain sight.

In an April 1988 article for the Los Angeles Times, writer Deborah Caulfield described the air of paranoia and fear surrounding the film’s release that month. Caulfield quoted an article by another newspaper that featured an interview with Wes McBride, the president of the California Gang Investigators Association, who apparently said that the film “would leave dead bodies from one end of this town to another.” She detailed the perspective of LA police chief Robert Vernon, who claimed his department might limit or ban Colors in movie theaters, and L.A. District Attorney James Hahn, who suggested that theaters could prevent violence by refusing to screen the film. (Neither man had actually seen the movie.) Eventually Hahn saw Colors, and withdrew his earlier censoring recommendations, but the damage had already been done. Caulfield wrote that despite the city attorney’s softening view, “some of the rest of the country’s news media were still dwelling on the original story. It became a one-sentence blurb on the front page of USA Today (‘Police fear movie will spark violence.’)”

In June 1989, Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing also debuted amid an air of controversy and sparked a similar moral panic—this time over the legitimacy and moral limits of Black protest. The movie, which takes place on the hottest day of the summer in late-’80s Brooklyn, concerns residents of a Bed-Stuy block, including neighborhood lush Da Mayor (Osside Davis), single mom Tina (Rosie Perez), pizzeria owner Sal (Danny Aiello), pizza delivery man Mookie (Spike Lee), Public Enemy-blasting Pied Piper Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), and Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), a community gadfly who attempts to boycott Sal’s restaurant (when he could just go to a different spot), because it does not feature Black people on its “Wall of Fame,” which only features Italian Americans. The neighborhood’s racial tensions build to a tragic and violent conclusion.

The film’s anthem, P.E.’s “Fight the Power,” was already under fire for lyrics that lambasted Elvis Presley and John Wayne, as well as for the anti-semitic comments of the band’s Minister of Information Professor Griff. Critics poured gasoline onto the blaze. Writing in New York Magazine shortly before the film’s American premiere, David Denby claimed that Lee “created the dramatic structure that primes black people to cheer the explosion as an act of revenge.” But how did he know what Black people were primed to do? He further warned that the film is a provocation to mimic the uprising in the film’s bloody final act:

Divided himself, Lee may even be foolish enough to dream, alternately, of increasing black militance and of calming it. But if Spike Lee is a commercial opportunist, he’s also playing with dynamite in an urban playground. The response to the movie could get away from him…The end of this movie is a shambles, and if some audiences go wild, he’s partly responsible. Lee wants to rouse people, to “wake them up.” But to do what?

This review is built on the assumption that Black people aren’t intelligent enough to see a film for what it is: a work of art, not an incitement to violence. Other reviews shared this paternalistic view of Black audiences. In the same issue of New York, Joe Klein asserted that David Dinkins, the only major Black candidate in New York City’s 1989 mayoral race, “will also have to pay for Spike Lee’s reckless new movie.” “If Lee does hook large black audiences,” he wrote, “there’s a good chance the message they take from the film will increase racial tensions in the city.” He also ascribed divergent responses to the film and its ending in Black and white viewers (not to mention the scores of viewers of different races). He wrote that what he called the “subtleties” of the film “are likely to leave white (especially white liberal) audiences debating the meaning of Spike Lee’s message. Black teenagers won’t find it so hard, though.” Newsweek’s film critic Jack Kroll called the film “dynamite under every seat.”

Lee’s response to the critical barrage was straightforward, and on point: “That’s irresponsible, to assume that black teenagers are some monolithic mob that’s not able to distinguish what’s real from what’s a movie.” Twenty-five years after the film’s release, Lee was still upset about those incendiary reviews. In 2014, he told Rolling Stone, “I don’t remember people saying people were going to come out of theatres killing people after they watched Arnold Schwarzenegger films.” No, all people did after seeing The Terminator was repeatedly quote the Schwarzenegger character’s catchphrase—“I’ll be back.”

Schwarzenegger’s recurring lethal cyborg—himself a time traveler across centuries—is another apt movie trope here, since in an American culture dedicated to the repression of disturbing conflict, everything comes back. Indeed, our current anxiety about movies featuring racial subject matter can be traced all the way back to Hollywood’s first blockbuster, D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915), one of the most influential films of all time. Celebrated for its technical virtuosity, including the introduction of cinema staples such as close-ups and fade-outs, as well as Griffith’s refinement of the cross-cut, an editing style he’d introduced in earlier films, The Birth of a Nation was an artistic marvel during its time. It’s the movie’s content that proved caustic. The film—adapted from the novel The Clansman, another lament for imperiled white supremacist rule in the South by Thomas Dixon Jr., author of The Leopard’s Spots—is a paean to the Ku Klux Klan, from Lincoln’s assassination to Reconstruction. The film is filled with the kind of stereotypical Jim Crow-era depictions of Black Americans that were even retrograde in 1915. The film is rife with images of lazy, menacing Black men. As film historian Donald Bogle notes in his book Hollywood Black: The Stars, the Films, the Filmmakers (2019), “while The Birth of a Nation was heralded as a technical masterwork, it would also be remembered as perhaps the most racially disturbing and distorted feature in American film history.” The NAACP denounced the film for its racism; Bogle notes that the organization successfully campaigned to ban and censor it in some cities.

In his history of the film, the film history professor Melvyn Stokes observes that no other movie engendered the kind of censorship The Birth of a Nation did, citing its inclusion in at least 120 censorship controversies from 1915 to 1973. But it had already made an outsize impact. Griffith and Dixon organized private screenings for President Woodrow Wilson at the White House, as well as for the entire Supreme Court at the National Press Club (the event apparently featured cheering and applauding throughout the film’s three-hour runtime). A 1915 Washington Post write-up of the Press Club screening records the attendance of Chief Justice Edward Douglass White, Jr., the Secretary of the Navy, and thirty-eight members of the Senate. (It’s hard to imagine a more apt example of institutional racism than this collection of influential figures at such an affair.)

It’s possible that the audience members, including the senators, Supreme Court justices, and cabinet members, had complicated feelings about the film; there’s a chance they privately decried its depictions. Maybe they pulled the director and author aside to critically interrogate the film’s baldly racist celebration of the Southern Lost Cause myth.

But the fact that Griffith and Dixon went to great lengths to effort to organize a private White House screening of The Birth of a Nation suggests that opinions in the room were already strongly aligned behind the film’s message. Wilson himself was a Southern partisan who toed the Lost Cause line in his histories of the United States. Justice White, who fought for the Confederacy, is widely believed to have been a member of the Ku Klux Klan (though some of the evidence for his membership is under dispute). Although Wilson’s exact take on The Birth of a Nation is also disputed, Bogle relays the president’s widely quoted response to the special viewing, an exclamation that the film “is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it all is terribly true.” If this was indeed Wilson’s reaction, he was far from the only aggrieved white viewer to rally to the movie’s white supremacist worldview. As Stokes notes, The Birth of a Nation played a role in bolstering white terrorism: “As the Klan rose and fell in the 1920s, the film functioned as a propaganda and recruitment film”—a practice that continued into the 1970s.

The “lightning rod” of controversy surrounding critical race theory, engineered by the GOP and its fellow travelers, is another way to write history with lightning: it’s a way of effecting lasting change by striking quickly, and neutralizing progressive charges in the cultural climate. Proponents of critical race theory bans in school curricula employ the familiar tactics of regional and national censors. In these hands, history that doesn’t align with the conservative platform might as well be fantasy—and dangerous fantasy at that. This limited conception of CRT likens it to fiction, which is why it then becomes an easy target for culture-war depictions of it as a menacing and subversive narrative, and thus fair game for censorship and banishment.

Indeed, the guiding logic here is not unlike the ritual Oscar-season invocation of “the magic of the movies,” which asks people to suspend their disbelief and buy in. But I believe in cinematic magic. In good movies, filmmakers make their tricks look easy. The positions of the anti-CRT movement are as transparently engineered as poorly done special effects, or an ill-conceived screenplay. Their shoddily constructed arguments are too vague to engage. There’s a reason why The Birth of a Nation was at the center of more than 100 censorship incidents in a sixty-year span: its detractors could point to its depictions and cogently argue against their distortions. They could prove how inaccurate the film’s claims were.

After the Academy Awards anoint its winners this weekend—its own “Wall of Fame,” if you will—it will be instructive to note how those films are immediately framed, and then to watch for changes in the aftermath of all the pomp and circumstance. A movie’s artistic legacy will take some time to properly assess. One day, a Best Picture is 12 Years a Slave, 2013’s top film: thanks to its widely acknowledged excellence, it’s been made available to students around the country; on virtually the next day, its access is imperiled. On another day, an industry-anointed film could be Driving Miss Daisy, which won 1990’s Best Picture Oscar, an award contemporary critics believe should have gone to Do the Right Thing, which wasn’t even nominated in that category. (Best Picture presenter Kim Basinger signaled this controversy with an off-script acknowledgment of Do the Right Thing’s snubbing, just seconds before Daisy’s producers came up to claim the Best Picture award.) Driving Miss Daisy, while often charming and amiable, is an ultimately dull and patronizing film; its Best Picture win is now seen as a product of the backlash generated by Do the Right Thing’s trashcan-through-the-window finale.

Daisy shows Blacks and whites in a more palatable dynamic, getting along in well-worn ways: Miss Daisy (Jessica Tandy) is a wealthy Jewish widow, and Hoke (Morgan Freeman) is her chauffeur. The film presents the 25-year friendship of a white woman and a Black man—take that, Joe Breen—codifying the kind of celluloid togetherness D.W. Griffith, who planted horror at the specter of “miscegenation” at the origins of the American film industry, would never conceive. Driving Miss Daisy’s enshrinement is a product of Hollywood’s ongoing interest in uplifting, post-integration interracial friendship narratives—what critic Wesley Morris calls “racial reconciliation fantasies.” On the other side of critical race theory is the mode of national story-telling that its disparagers prefer: a racial reconciliation fantasy of a past best approached the way one views a just-OK movie playing for the nth time on cable—you might have it on the background for its comfort and familiarity, but you don’t actually watch it.

This imaginary conservative-sanctioned film is one in which historical actors (Black people, of course) have driven Miss Daisy (every Miss Daisy), eventually saved enough to purchase her car, taxi’d for a while, then signed up for Uber—Lyfting oneself up by one’s bootstraps—before ultimately breaking down, as all workaholics do. At that point, they’ll be carried away to heaven, that big old cabin in the sky.

It could well be that Americans, at long last, are getting tired of seeing this movie. To judge by recent school board elections in which rightwing activists trotted out the racial reconciliation fantasy as the stuff of bona fide history curricula, the plot has grown threadbare and the dialog unconvincing. But to ensure that this narrative doesn’t make another Terminator-style return engagement, people interested in telling the truth must heed the model of the NAACP as it fended off the toxic fallout from the debut of The Birth of Nation: We must fight fantasy with facts.

Niela Orr is a writer, a story producer for Pop Up Magazine, and a contributing editor of The Paris Review.