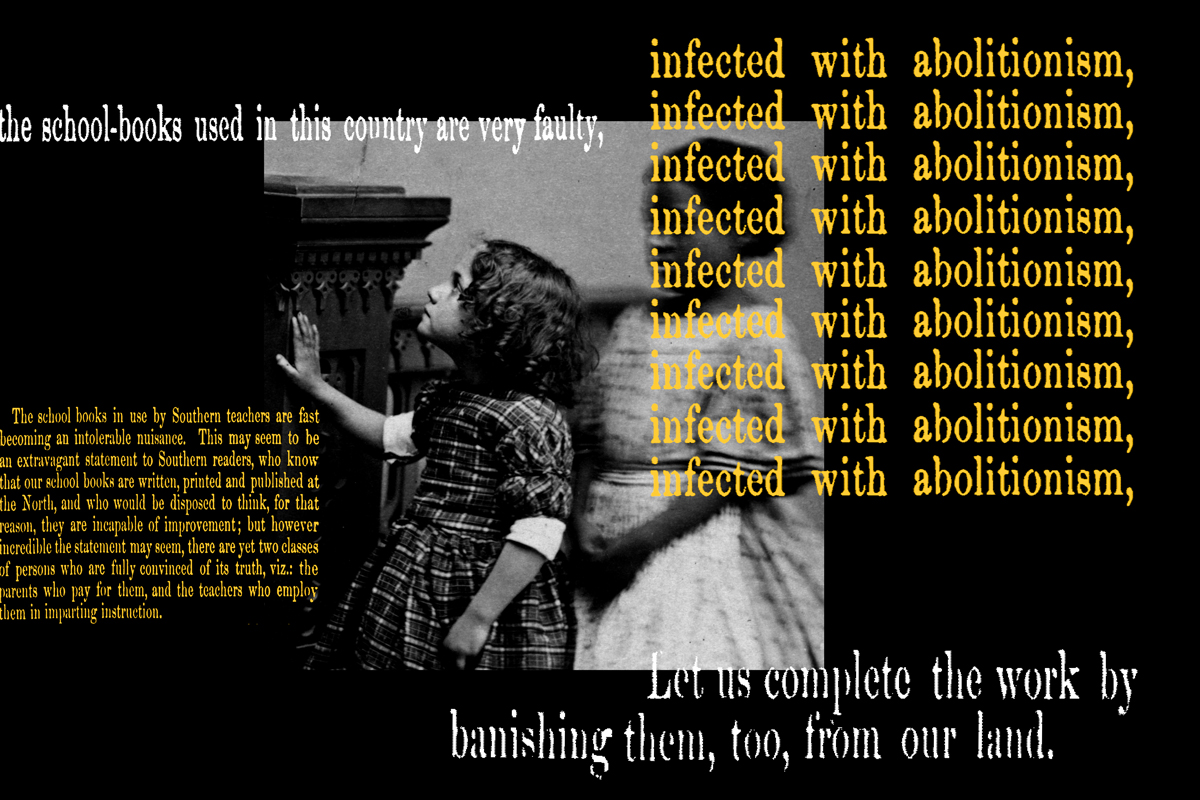

“Oppressive language does more than represent violence; it is violence; does more than represent the limits of knowledge; it limits knowledge. Whether it is obscuring state language or the faux-language of mindless media; whether it is the proud but calcified language of the academy, or the commodity-driven language of science; whether it is the malign language of law-without-ethics, or language designed for the estrangement of minorities, hiding its racist plunder in its literary cheek – it must be rejected, altered and exposed. It is the language that drinks blood, laps vulnerabilities, tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism as it moves relentlessly toward the bottom line and the bottomed-out mind. Sexist language, racist language, theistic language—all are typical of the policing languages of mastery, and cannot, do not permit new knowledge or encourage the mutual exchange of ideas.”

—Toni Morrison, Nobel Lecture, December 7, 1993.

Almost thirty years have passed since these words were first spoken—and it seems as though not much time, if any, has passed at all. We’re no smarter about, or better prepared for, Toni Morrison’s admonitions than we were back when the Internet was still an unsubstantiated rumor in most households, Donald Trump was considered no more dangerous to our democratic way of life than any other recurring guest on what was then still “Live with Regis and Kathie Lee,” and politicians on both sides of the aisle generally agreed that getting tough on Black-on-Black crime was a bigger priority for achieving social justice than directly addressing racial inequality.

Now it’s Morrison, three years since her death at 88, who’s being stigmatized by the thought police she’d warned us against in Stockholm; the “oppressive,” “malign” language aimed at “limit[ing] knowledge,” “designed . . . for the estrangement of minorities”; that “tucks its fascist boots under crinolines of respectability and patriotism…” and so forth. It’s almost as if in accepting her Nobel Prize, she’d summoned up from beneath several rocks the hysteria that propelled Republican Glenn Youngkin to the Virginia governorship last fall in a demagogic panic over how novels like Beloved, Morrison’s groundbreaking 1988 masterwork about a onetime slave haunted by killing her two-year-old daughter to spare her the horrors of bondage, were being taught in the state’s public schools.

The furor opened a new front in the ongoing culture wars waged by the right, though it’s really an old hoary front of prohibiting access to books deemed offensive to whatever communities feel threatened by their…what, exactly? Their politics? Their sensibilities? Their existence? It can’t be their content, precisely, as there are some Beloved assailants who admit they haven’t read it or any other of Morrison’s books similarly under attack—notably her breakthrough 1970 novel, The Bluest Eye about a young Black girl growing up during the Great Depression believing that having blue eyes will subdue her deep sense of inferiority. Besides racism, there are subtexts of incest and child molestation in The Bluest Eye that have aroused the ire of school boards like the one in Virginia Beach, Va., one of whose members said she’d read pages of that book that transported her into “utter disgust.”

But not, apparently, the whole book—and selectivity, or at least a dearth of either context or specific details, appears to be the norm in these battles over books. As with just about everything else within the intersection of politics and culture these days, “feeling” holds primacy over “thinking” about anything. Last fall’s brushfire during the Virginia gubernatorial campaign over Beloved in Virginia was apparently first set off in 2013 when the school-aged son of a Fairfax County woman told his mother that Beloved gave him “nightmares.” The woman, Laura Murphy, gave this account in a TV ad for the Youngkin campaign and her son Blake, who in the near-decade since has become a lawyer working for the Republican National Committee lobbying for greater parental control over what students read in school, told the Washington Post he thought Morrison’s book was “disgusting and gross” and “hard for me to handle.”

One thinks of the line from Beloved, “Watch out for her, she can give you dreams” that the late literary critic and Morrison advocate John Leonard borrowed for the title of a review of her 1992 novel, Jazz. Novels, if they’re worth your time, are supposed to give you dreams, good and bad, and the complaints by Blake Murphy and his mother make one wonder if it’s the images in Beloved (which is, after all, a ghost story) that were so deeply troubling—or whether it was what those images say about America’s savage history. Because the public discussions on such matters never dig beyond the rhetoric of fear and righteousness—“calcified,” to borrow an adjective from the Nobel Laureate’s address—we’re never going to know for sure.

The war on Toni Morrison is, of course, part of a larger philosophical battle over “critical race theory,” which insists on a comprehensive reckoning in and out of classrooms with the racism embedded in America’s institutions and attitudes. It has already affected state and local elections, driven school boards up a wall and perplexed a mass media that doesn’t quite grasp the concept (or know exactly what it means).

One wonders if it’s the images in Beloved (which is, after all, a ghost story) that were so deeply troubling—or whether it was what those images say about America’s savage history.

It would make the present lurch into know-nothing grievance politics a whole lot easier to bear if the war on critical race theory turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to Toni Morrison’s reputation. Whenever an author is demonized by authority figures, whether they’re rigidly, aggressively authoritarian in their politics or not, there’s often an attendant irony: the more socially transgressive a book becomes, or is perceived to be, the more alluring it is to those who’d rather not be told what and what not to read. (See the case of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, a graphic novel of Holocaust history that rocketed to the top of the Amazon bestseller list after an overzealous school board in Tennessee dropped it from the curriculum.)

By the time she’d died in 2018 at 88, Morrison had achieved the kind of lofty stature in American life and letters that assures posthumous longevity while making her inscrutable, if not inaccessible, to whole strata of the public-at-large. For every reader I’ve encountered who’s enraptured with and committed to Morrison’s body of work, there are at least a couple of others who are intimidated at best by her intricate verbal music as well as by her graphic imagery. For these readers, Morrison’s prose can be a Gordian knot of psychic inference and poetic discursiveness. So it could well be a literary boon of sorts for bigoted and/or apprehensive spoilsports regulating school curricula to inadvertently inject an unruly outlaw streak into Morrison’s literary persona. Maybe high schoolers susceptible to the if-they-say-it’s-bad-it-must-be-good temptation won’t be as intimidated by the allusive enigmas of the Morrison style and will give not just Beloved or Bluest Eye a deeper read, but also Sula, Song of Solomon, Jazz, Paradise, A Mercy or the recently republished short story, Recitatif (about which more later).

But it’s just as possible that prohibiting or discrediting Morrison’s books will just give people excuses to ignore or bypass them entirely. In the past, young readers were drawn to forbidden or banned literature by curiosity, and if there’s one thing I’ve noticed among post-millennial students in high schools and colleges, it’s that their inclination toward curiosity is checked by that damned Internet I alluded to earlier. Why bother chasing down or seeking out anything on my own when I can just click a search engine and all the answers to life’s mysteries are all listed in front me? the logic goes.

It would make the present lurch into know-nothing grievance politics a whole lot easier to bear if the war on critical race theory turned out to be the best thing that ever happened to Toni Morrison’s reputation.

As with most generalizations, this is likely too broad and spurious an assessment. But as many of my friends who teach at various levels of the educational system can attest, it’s more of a challenge to get students to even consider the possibilities for deeper mysteries to probe and more satisfying resolutions to extract.

It may also be time to consider the possibility that we’re all going about this “racial dialogue” thing the wrong way. Mostly we need to stop worrying about making Black and White people “feel better” about being what they are. “Feelings,” as I’ve suggested earlier, are what got us all into this mess in the first place. Somebody needs to break the news, however gently, that none of us is as “Black” or as “White” as we think we are, thanks in large part to an ongoing cultural transaction that began centuries ago and has led to new and different ways of perceiving Black and white, or, if you will, pink and brown.

Which is where the aforementioned Recitatif comes in. Morrison’s only published short story, which first appeared in print in a 1983 anthology of works by African-American women writers, has this year been re-released in book form. It was originally written, according to Morrison, as “an experiment in the removal of all racial codes from a narrative about two characters of different races for whom racial identity is crucial.” It follows the static and fraught long-term relationship between two young women, Twyla and Roberta, both of whom come from poor backgrounds and become acquainted during a four-month stay in a children’s orphanage called St. Bonaventure in the late 1960s. Both are eight years old and have in different ways been abandoned by their mothers. From the beginning, Morrison makes it clear that one is Black and the other is White, but doesn’t directly tell the reader which is which.

They each eventually leave the orphanage, and the story has them meeting at four different times over the next ten-to-twenty years. Their lives take different, at times jolting, turns and yet they remain linked for all time by the shared memory of an incident at the orphanage involving a “sandy-colored” old woman named Maggie “with legs like parentheses” who worked in the kitchen and was unable to speak.

What makes Morrison’s story more than a mere intellectual puzzle in working out the racial identities of its main characters are the ways in which she orchestrates signifiers in speech, dress, and mannerism to make readers acutely aware of the distinctions between Twyla and Roberta without disclosing which of them is Black or White. She thus forces us to engage them as human beings without in any way mitigating how important the distinctions are between them. In one encounter, for instance, Twyla is working a counter at a Howard Johnson’s while Roberta appears at the diner with “two guys smothered in head and facial hair” en route to a west coast appointment with Jimi Hendrix. Aha! So now we know….well, (again) what exactly? Is it a given that Roberta is white because she’s rich enough to travel in such fast company? Or is it a greater possibility that Roberta is Black because she’s meeting up with a Black rock icon while Twyla is moored on an unnamed thruway in a decaying restaurant? The difference is there and it matters—but maybe not as much as it should to those counting on these certainties to keep them anchored to these stories and the worlds they evoke.

It’s almost as if Morrison is answering her shrillest critics who think she’s somehow claiming greater privilege for her and her people because of the physical and psychological indignities brought about by white racism. Recitatif re-emerges from the shadows of the past to remind us all that none of us should be as sure as we think we are about who we are, what doors have been open (or closed) to us, and what we’ve allowed to define us. The reminder likely won’t reach the scolds, prigs, opportunists and fear-mongers who need to hear it most. But it reaffirms Toni Morrison’s power to tell us things we didn’t, or don’t, want to know.

Gene Seymour has written about film, music, politics, and (even) baseball for The Nation, Bookforum, CNN, and other outlets. He lives in Philadelphia.