As the national Republican party gears up for a critical midterm election—and sizes up its chances to recapture both houses of Congress—it’s hit upon a potent culture-war crusade to revive a Trumpian mood of white grievance among its base without Donald Trump on the ballot. The pivotal strategy here is the demonization of critical race theory, a method to analyze the ways racism is codified into American law. Since 2020, conservatives have advanced legislative mandates in more than two dozen states to ban the framework from K-12 schools in the name of creating an inclusive environment free from “psychological distress.”

As in so many other theaters of culture war, the Texas GOP is at the vanguard of the CRT crackdown—not only enacting curbs on classroom instruction, but also compiling exhaustive lists of banned and verboten books for state-funded schools. In October 2021, Texas GOP state Rep. Matt Krause, who chairs the House Committee on General Investigating, sent a letter to superintendents throughout the state to gauge just how far the precepts of CRT had seeped into school library collections. As part of this attempt to gather “preliminary information” on “the welfare and protection of state citizens,” Krause finished his letter with an addendum of 850 books, instructing all Texas schools to tell the committee how many copies of each title they have, and to itemize how much money they spent on the books.

Krause explains that he’s instituting this far-reaching book ban in order to purge schools of material that may cause “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex or convey that a student, by virtue of their race or sex, is inherently racist sexist or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.” The targeting of discomfort that’s experienced “consciously or unconsciously” means, on the face of things, that virtually any title or author can be fair game under Krause’s ban. And sure enough, well-known African American authors such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, Isabel Wilkerson, and Ibram X. Kendi made Krause’s list, but there is a telling omission: books written by pioneering critical race theorists Kimberlé Crenshaw and Derrick Bell are notably absent. Texas schools are not actually teaching critical race theory—but that has in no way deterred state lawmakers keen to exploit the burgeoning mood of racial retrenchment on the right.

This means that Krause’s list is a confession: conservatives are not attempting to whitewash history so much as they are setting out to rewrite history. There’s a clear precedent for this sort of crusade, fittingly enough, in the kindred moral panics over egalitarian racial literature fomented by the American Confederacy and prior generations of the slave order’s defenders in the antebellum South. And it’s vital to revisit the saga of this older episode of racially driven book banning for the simple reason that this very effort to stage-manage an ideologically interested account of our racial past is a prime example of the sort of material that would likely be expunged from school curricula under pending CRT bans.

Michael Bernath, author of the 2010 book Confederate Minds: The Struggle for Intellectual Independence in the Civil War, chronicles the Confederacy’s attempt to create a distinct culture from their Yankee enemies. “In order to be permanent and meaningful,” writes Bernath, “the separation between North and South had to be cultural as well as political.” Northern textbooks dominated the South, and southerners who encountered abolitionist doctrines in textbooks viewed such classroom materials as a vehicle for cultural colonization. Drawing from leading figures in confederate education, quarterly magazines, and education journals, Bernath describes the South as a paranoid society, anxious over what its leading thinkers saw as the prospect of imminent cultural decimation.

Like the antebellum Southerners who viewed themselves as heroic resisters of Yankee persecution, today’s conservatives gravitate to the posture of the aggrieved victims of a stealth cultural takeover.

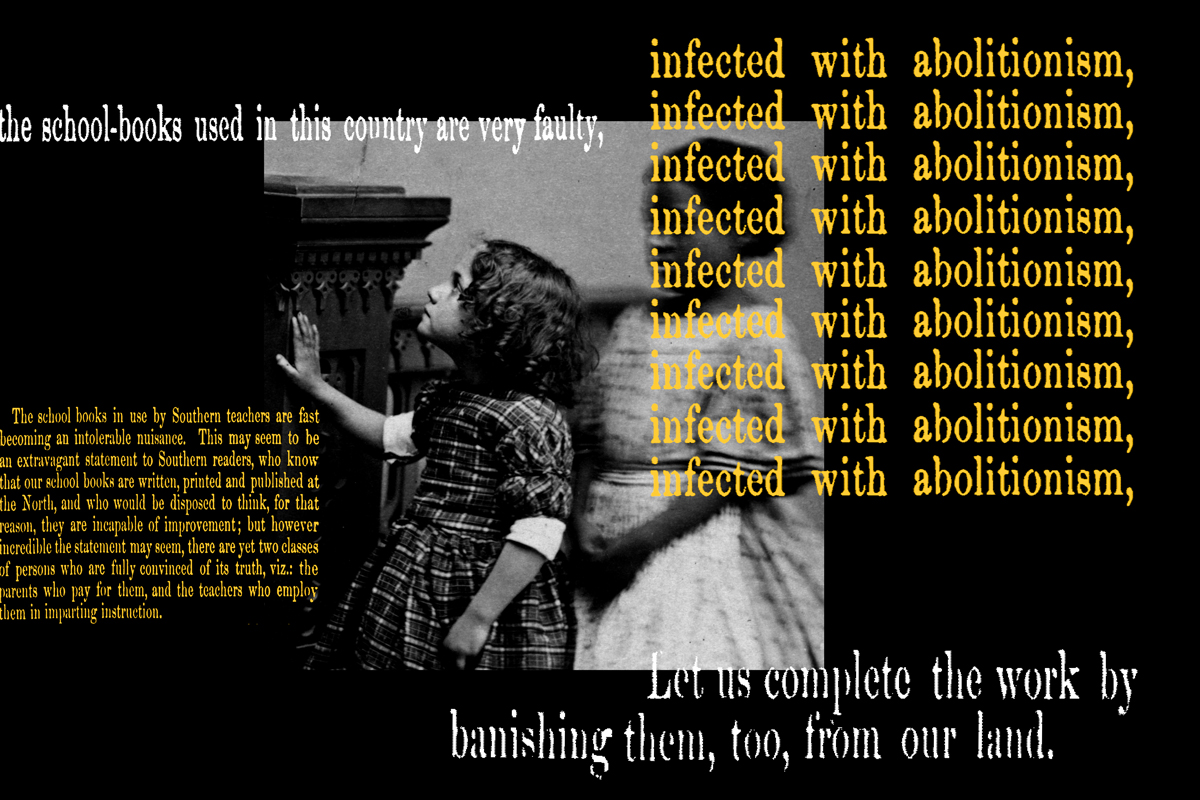

“Let the State Legislatures at the South at once take up the subject, which is of more importance than any other that can be brought before them,” wrote the editors of De Bow’s Review, a southern magazine prominent in the mid-nineteenth century. The subject in question was the presence of books “infected with abolitionism” in southern schools. The editors’ commentary preceded an article called The Future of Revolution in Southern School Books, penned by an anonymous Virginian who bemoaned northern influence in Southern education. “The books rapidly coming into use in our schools and colleges at the South are not only polluted with opinions and arguments adverse to our institutions, and hostile to our constitutional views,” the Virginian wrote. This attack was more than a salvo in the nineteenth-century culture wars: confederate propagandists saw it as of a piece with the actual war between the Union and the South. For them, the abolitionist doctrines unloosed in their schools represented an intellectual and academic pincer move—a flank that threatened the cultural success of the southern war effort. “They have left behind them a legacy of school books,” the Virginian wrote of their northern antagonists. “Let us complete the work by banishing them, too, from our land,”

The parallels with Krause’s bid to purge Texan schools of materials deemed too incendiary or divisive for public school students are all too plain. Indeed, this same mood of a hallowed cultural tradition under siege was present at the creation of today’s anti-CRT crusade. Christopher Rufo, the lead curator of the hysteria over critical race theory, routinely showcases the hair-trigger victim’s outlook and the brash malignance of the confrontational confederate in his writing and public appearances. “Conservatives need to wake up,” Rufo told Tucker Carlson in the fateful Fox News hit in 2020 that launched the present CRT moral panic. Rufo explained that critical race theory was nothing less than “an existential threat to the United States. And the bureaucracy, even under Trump, is being weaponized against core American values. And I’d like to make it explicit: The president and the White House—it’s within their authority to immediately issue an executive order to abolish critical-race-theory training from the federal government. And I call on the president to immediately issue this executive order—to stamp out this destructive, divisive, pseudoscientific ideology.”

Rufo’s appeal resonated because today’s conservatives, like the confederate book banners of 150 years past, view themselves as a colonized people, culturally oppressed by a progressive regime. Again, the Old South precedents here are chilling and revealing. In 1861, George E. Naff, president of Soule Female College in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, published a review of northern textbooks for a Methodist religious journal; in it, he assailed northern educators for “the most dangerous and incendiary doctrines in morals and politics.” Books attacking slavery and advocating racial equality, he explained, set out to contaminate ‘‘the youth of the South with the [same] foul miasma that taints the Northern atmosphere.’’

Naff’s essay, “Cleveland’s Textbooks,” attacked Charles Dexter Cleveland’s A Compendium of American Literature. Southern critics wrote scathing reviews portraying Cleveland’s book as abolitionist propaganda that featured anti-slavery authors such as William Jay, James Wilson, John Quincy Adams, William E. Channing, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. Naff urged southerners “to be ever vigilant, ever on the alert for books that come from Northern book-makers and Northern press[es], and to frown down, write down, condemn and spurn every one containing this covert abolitionism and incendiarism. . . . Let us, by a proper watchfulness, defeat the diabolical designs of these unscrupulous fanatics.”

Toggle back to right-leaning social media accounts in the twenty-first century, and the same throughlines promptly emerge. “We have a problem and need help,” tweeted Kathy May on October 16th. May is a parent from Keller ISD, a district located in Matt Krause’s Tarrant County. The tweet called out a book called Gender Queer, a memoir written by Maia Kobabe, that includes two people engaged in a sex act. May, who moved from California to Texas two years ago to flee liberal influence, was shocked to see “leftism and progressivism” in Keller ISD. “This book was brought into Keller ISD, please help us make parents aware of the danger of the cultural changes our society is making, when people say they’re going after our kids, you need to listen, because they are,” May tweeted.

Other changes afoot in Keller ISD have helped stoke the mood of free-floating moral panic. In 2006, the district ranked 18th of 26 in diversity in Tarrant County; out of 27,905 students enrolled in the district, 71 percent were white. But there’s been a marked demographic shift in the district over the past 15 years. Currently, 35,352 students are enrolled in Keller ISD; 55 percent are white.

The demographic trends in play in Keller ISD and districts like it throughout the country highlight the strategic importance of the school mobilization for the Republican Party. For all the alarm over runaway progressive school agendas voiced by individual parents like May, the raging right-wing culture war over critical race theory represents a crucial effort to regain control over Republican districts that turned blue after the 2020 presidential election. The eager embrace of the CRT crackdown was among the factors that seem to have contributed to Republican Glenn Youngkin’s victory in the Virginia gubernatorial race—in a state that Joe Biden carried by ten points in 2020. Matt Krause, who is running for Texas attorney general, represents Tarrant County, which hadn’t voted for a Democrat for president since 1964. In the 2016 presidential election, Trump won Tarrant County with roughly 52 percent of the votes to Clinton’s 43 percent. In 2020, however, Biden narrowly won Tarrant County with 49.3 percent of the vote, over Trump’s 49.1.

Krause represents a district that is diversifying, and the tensions of this diversification are readily transmuted into the politics of white grievance. Such districts were also prime recruiting grounds on the right for the January 6 insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, seeking to overturn the results of the 2020 presidential balloting. A recent study from the University of Chicago showed the odds that a county would send an insurrectionist to the Capitol was six times higher in counties where the percentage of non-Hispanic whites declined. Odds of participating in the insurrection increased three-fold for Americans who believed that Blacks and Hispanics are overtaking whites, and increased two-fold among Americans who fear Blacks and Hispanics will have more rights than whites.

This fear of cultural replacement clearly lies at the root of the CRT panic; it has emerged as the great follow-on culture-war mobilization to channel the activist outrage of Jan. 6. The political appeal is so potent here that strategists on the right are rapidly dropping their philosophic distrust of state power to galvanize the electorate behind the state-level CRT bans: Without missing a beat, they have embraced the sort of top-down state mandates they’ve resisted over the course of the Covid pandemic; for them, clearly, critical race theory represents the real viral threat to their cultural survival—a social pathology that must be eradicated through government bans.

Mary Lowe, chair of the Tarrant County chapter of Moms for Liberty, a right-leaning national organization founded in January 2021, reprises Naff’s plaints over a dangerous and seditious body of doctrines seeking to turn the world upside down. “What this is all about is a socialist ideology being indoctrinated to the American student young enough that it would conflict with the parent or the family of origin’s ideology,” Lowe said. “Moms for Liberty has a strong stance that there are an enormous amount of literary books that are more aligned with academics and expanding the mind without such a heavy focus on sexual content.” Like the antebellum Southerners who viewed themselves as heroic resisters of Yankee persecution, today’s conservatives gravitate to the posture of the aggrieved victims of a stealth cultural takeover, suddenly discovering their cherished way of life is under siege by liberal doctrines.

As Bernath points out, “only rarely did Confederate critics direct their barbs at particular works or authors, preferring instead to indict Yankee culture in its entirety. When they did cite specific examples, only the most extreme, like Cleveland’s anthology, would do.” Again, one doesn’t have to look far into the present-day CRT panic to see the same methods at play: To excoriate critical race theory, Kathy May and Mary Lowe assail the illustrations in Gender Queer as pornographic and conflate the images with critical race theory when they have nothing to do with each other. “The Confederate critique of northern culture was built primarily on forceful assertion rather than thoughtful analysis,” Bernath explained. “With independence declared and war looming, this was no time for nuance or equivocation, and southern nationalists saw no need to indulge in subtlety.”

“They may not call it critical race theory, but they’re calling it equity, diversity, inclusion. They use culturally responsive training for their teachers. It is fundamentally CRT. It’s dividing our children into victims and oppressors and what’s a child supposed to do with that?” said Patti Hidalgo Menders, president of the Loudoun County Virginia Republican Women’s Club. Menders believes diversity and inclusion training “becomes less about merit and it becomes more about, oh, we gotta give the people of color this advantage.”

In the midst of culture war rhetoric such as this—pitting individual perceptions of, and attitudes toward, race against one another—critical race theory offers a corrective: if society understands the problem of structural racism, society can intervene and dismantle the structure. This is heresy to the longstanding Republican doctrine holding that individual strivers must lift themselves up by their own bootstraps—a credo that centers individuals as pathology and not the structures that govern society. “I do not support defunding police,” Matt Krause said. “The murder of George Floyd was tragic and unnecessary.” Pundits may differ in the political efficacy of defunding the police as both a slogan and a program, but it is a structural critique, one that demands that not only bad police officers be held accountable but that policing deserves its own indictment. And this is why critical race theory conjures a special malice in the psyches of white conservatives who view diversity, progressivism and structural reformation as the stalking horses of their own demise.

Critical race theory conjures a special malice in the psyches of white conservatives who view diversity, progressivism and structural reformation as the stalking horses of their own demise.

To ward off unwelcome “cultural changes,” Republicans hide behind children, using them as an amulet to dispel progressive spirits like gay marriage, gender equality, and critical race theory. Is society to believe the political party that opposed gun control after twenty elementary school children were murdered at Sandy Hook, and allows the death of children from faith-healing exemptions, immunity for parents who reject medical care and vaccine mandates for their children in lieu of prayer, is the party of safe space for children?

This is why it’s crucial to recognize that even as the leaders on the American right inveigh against the alleged trespasses of CRT in our schools, they are also deploying state power to closely police sexual identity and behavior among school-age kids: As the Tarrant County crusade against Gender Queer clearly shows, one moral panic merges seamlessly into the other. Health education programs in South Carolina are forbidden to discuss “alternate sexual lifestyles from heterosexual relationships…except in the context of instruction concerning sexually transmitted diseases.” In Louisiana, “no sex education course offered in the public schools of the state shall utilize any sexually explicit materials depicting male or female homosexual activity.” In Oklahoma, AIDS prevention education shall specifically teach students that “engaging in homosexual activity is now known to be primarily responsible for contact with the AIDS virus;” Florida’s health education program is devoted to “teaching the benefits of monogamous heterosexual marriage.”

Republicans are poised to enact a bevy of anti-trans bills in state assemblies, ostracizing trans students from sports, and restroom usage. North Carolina passed a bill to limit the use of critical race theory, while at the same time legislating indoctrination into cisgender roles. If passed, the bill would require teachers to notify a student’s parents if the student displays “symptoms of gender dysphoria, gender nonconformity, or otherwise demonstrate a desire to be treated in a manner ‘incongruent with the minor’s sex.’ ” Despite the rising rate of suicide among America’s adolescents and youth, Republicans have no qualms about discriminating against trans youth, who are among the highest at-risk population for suicidal ideation. On the right, the psychological distress and suicide of trans youth isn’t a divisive issue—even though for actual school children it’s a far more pressing source of discomfort, trauma and division than race-themed instruction will ever be.

“We’ve needed new language for these issues,” said Christopher Rufo. In his account, critical race theory carries “connotations [that] are all negative to most middle-class Americans, including racial minorities, who see the world as ‘creative’ rather than ‘critical,’ ‘individual’ rather than ‘racial,’ ‘practical’ rather than ‘theoretical.’ ” The anti-critical race theory movement is thus also an attempt to preserve Republicans’ cultural relevance, which is reliably channeled on the right through anti-Black sentiment—bother covert and overt. “Strung together, the phrase ‘critical race theory’ connotes hostile, academic, divisive, race-obsessed, poisonous, elitist, anti-American,” Rufo said. “ ‘Critical race theory’ is the perfect villain.”

Here again, Rufo has said the quiet part out loud: The villain is not critical race theory as an academic method of inquiry; rather, it is the people—the “hostile, academic, race-obsessed, anti-Americans”—who criticize America’s history as an anti-Black social order. This, too, is a very old refrain among the defenders of the antebellum status quo in the south—and represents still another reason that we need to ensure that all Americans, young and old, can learn the unvarnished truth about the enduring legacies of American racism. School board inquisitions and midterm elections aside, a country that cannot escape its past will be condemned to blankly wondering why its own history continues to repeat itself.

Anthony Conwright is a writer and AAPF fellow living in New York City. Follow him on Twitter @aeconwright.