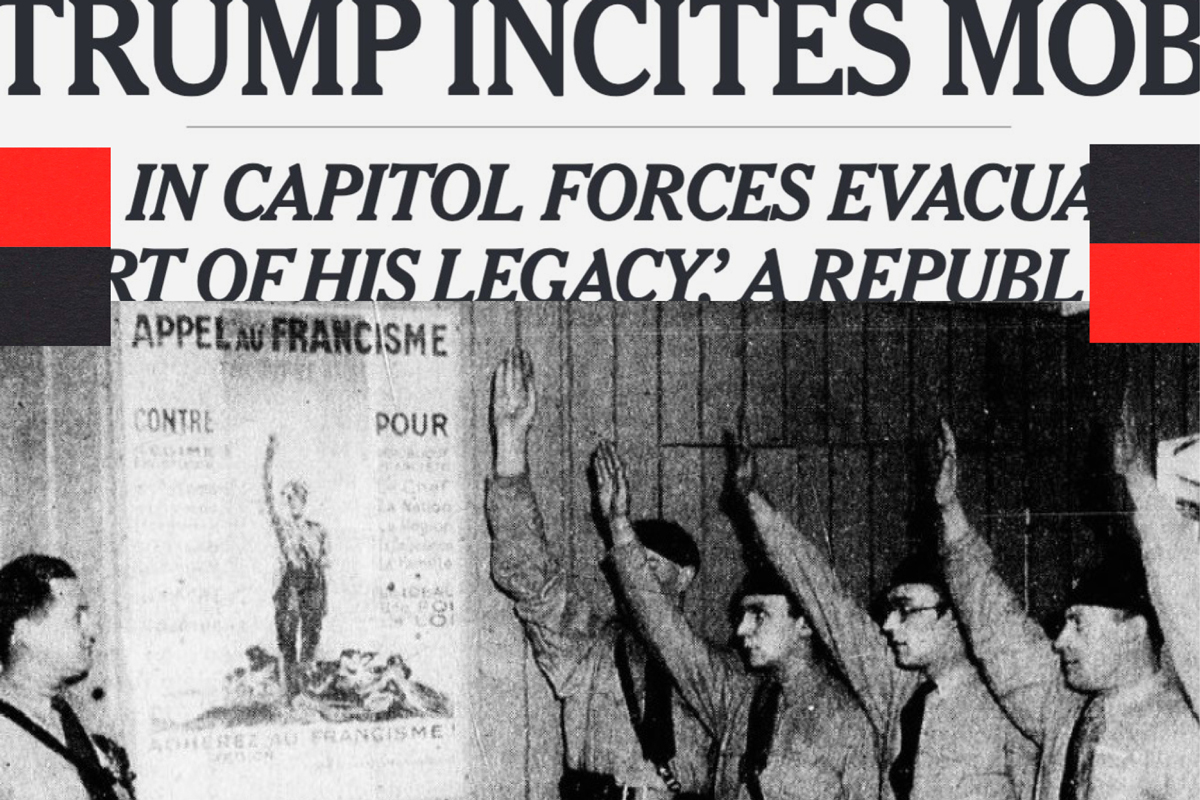

The day after last year’s insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, I emailed the historian Robert Paxton to ask his thoughts on this stark new turn in American politics. Paxton, author of The Anatomy of Fascism and the leading scholar of Vichy France and the French far right, had been previously reluctant to use the term “fascism” to refer to Trump and Trumpism, but January 6 changed his mind. “Yesterday’s use of violence against democratic institutions crosses the red line,” he wrote. “There is a spookily close parallel with an event that occurred in the late French Third Republic—the attempt by right-wing militants to march on the Chambre des députés in the night of February 6, 1934.”

The French uprising may be comparatively little known today, but the anti-New Deal American right took great interest in it at the time—indeed, the siege of the French parliament furnished the inspiration for the abortive “business plot” that sought to unseat President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. And in the present-day context, there are a number of eerie parallels between the events of January 6, 2021 and February 6, 1934: in both cases, a loose coalition of right-wing groups and their sympathizers attacked the national legislature in an attempt to disrupt the recognition of a new government; in both cases, the mobs were animated by conspiracy theories and myths about their opponents; in both cases, the crowds united old and new political tendencies on the right and included many military veterans. And in both cases, the meaning and significance of the event was immediately contested in a highly polarized public sphere. In 1934, the dead and wounded rioters became martyrs for the far right, just as Trump and others have attempted to do with Ashli Babbitt. For the participants and sympathizers, the riots on February 6, 1934 signaled a patriotic stand against corruption and the machinations of the left and the first hints of a long hoped-for “national revolution.” For the left, it represented the undeniable arrival of the fascist threat in France.

But it is here that the parallels begin to end. The riots on February 6, which resulted in greater loss of life than the January 6 action did, did not enter the legislative chamber, but did bring down a government: the new premier Édouard Daladier resigned the next day after weathering several votes of no confidence. On January 6, the mob entered the chamber, but could not change the course of political events. To the French left, the events of February 6 represented a coordinated plot to overthrow the Republic, an attempted “fascist coup.” This judgment proceeded to guide their energetic political response: a general strike and ultimately unification of the disparate left-wing parties in the Popular Front. In historical retrospect, we know there was no coup plot: February 6 was not the result of a centrally directed move against the constitutional order, even if the anti-parliamentary leagues on the street had close ties to some right-wing members of parliament.

In the absence of a strong political response from the left, the main propaganda efforts to frame and define the meaning of January 6 have been on the right.

As we are learning day by day from the press and the proceedings of the congressional committee investigating January 6, the Capitol insurrection was a far more centralized affair: members of Congress consulted with the White House on an entire strategy on how to perpetuate the myth of election fraud as the reason for Joe Biden’s victory over Trump while seeking to block the certification of the election. There was no leader during the events of February 6 1934, but Trump was present at a White House meeting that encouraged Vice President Mike Pence to refuse to certify the election. Trump directly encouraged the crowds to march on the capital; to “fight” and show “strength.” Then for many hours he declined to denounce their actions or demand their retreat. It also appears that he resisted sending in the National Guard to restore order. Senator Ben Sasse told Hugh Hewitt that Trump was “delighted” with the scenes unfolding on television.

Further comparison of these two events yields a paradox: in the first case, there was no actual coup attempt, but the French left was convinced there was and this elicited a massive political response. Meanwhile, on January 6, it appears there was a coordinated attempt to illegally seize power, but there’s not even an agreement on how to characterize it: was it a “coup,” an “insurrection,” a “riot,” a “putsch,” or “vigilantism?” Left and right in France contested the meaning of February 6, but today in the United States the meaning of January 6 is contested even on the left. Despite—or perhaps because of—insistent headlines bringing new revelations, the public’s interest and clear understanding of the event seem to have waned.

In the absence of a strong political response from the left, the main propaganda efforts to frame and define the meaning of January 6 have been on the right. For instance, Tucker Carlson’s three-part documentary “Patriot Purge” set out to depict the violent storming of the Capitol as a false flag operation, provoked by left-wing activists and the national security state, to justify a crackdown on the right. This false narrative worked to resurrect the battered conceit of right-wing American innocence on two levels: it preserved the “real American” purity of the participants while impugning the truthfulness and patriotic fidelity of their opponents. In this backward-spooling account of an uprising encouraged and provoked by the executive branch and its congressional allies, the rioters were accorded an all-encompassing sort of moral absolution. They were at once virtuous and justified–which meant in turn that whatever violence or law-breaking they’d fomented or committed was not actually their fault.

There is an apparent contradiction in saying the Capitol insurrection was essentially staged, but also that the actions of its participants were noble and good. But this kettle-logic actually lends to the propaganda power of this explanation: It allows for a variety of responses, all of which are exculpatory in one way or another. Those who unequivocally support January 6 can endorse it as the real truth behind the insurrection, repressed by the press and other “enemies of the people.” Meanwhile, more ambivalent sympathizers with Trump and his enablers who’d been initially shocked, frightened, or repulsed by the seizure of the Capitol can claim innocence and redirect anger back on their opponents.

This marks still another instructive analogy to the late Third Republic: in 1937, the Socialist Minister of the Interior uncovered a far-right terrorist group that actually had been planning a coup against the sitting government. The conservative press quickly launched a counter-offensive that portrayed the coup plotters as patriots and victims of a conspiracy by the intelligence services to discredit the entire French right. The charge was now that the coup plot was itself a false flag and a hoax created by the left. One citizen remarked of the arrests, “We understand that every French citizen who doesn’t adhere to the Popular Front will lose all their goods and liberties.” This blame-shifting account was completely delusive; but like the same line adopted by Trumpian propagandists 84 years later, it powerfully reversed the coordinates of a narrative that was potentially toxic to an overtly antidemocratic and violent brand of authoritarian politics, magically anointing its adherents as the real victims. Thus Tucker Carlson blithely asserts, again with zero credible evidence, that the events of January 6 were choreographed solely to serve as “a pretext to strip millions of Americans, disfavored Americans, of their core constitutional rights.” The degree to which this propaganda offensive has actually increased the constituency for the far right is still unclear, but it has prevented January 6 from becoming a rout and turned it into a rallying point.

In actual fact, the response has been rather muted, partially perhaps to avoid the appearance that charges like Carlson’s have any basis in reality–which counts as another success of the propaganda offensive.

In the realm of mass politics, meanwhile, there’s an asymmetry between the defenders of the Trumpian putsch and the forces of democratic dissent. That’s because, institutionally speaking, a robust American left barely exists–in spite of another steady barrage of right-wing canards insisting that an all-powerful left-wing conspiracy operates in Washington’s halls of power. France in 1934 had a Socialist party, a Communist party, and the middle-class Radical party, with its own sizable anti-fascist center-left contingent. It also had a massive organized labor movement closely tied to the parties of the left. So in response to February 6, the French left-wing parties could call for a general strike and massive demonstrations, and the labor unions would answer.

In America, by contrast, there are no left-wing parties, there is a small left contingent of one party, and organized labor has been totally gutted. Far-right groups in France could be driven off the street by the appearance of mass demonstrations. In the United States, antifa tactics dictate a kind of counter-paramilitarism of small groups that’s easily turned into propaganda fodder for the right. There were recent massive demonstrations surrounding the George Floyd murder, but this did not yield a long-term organized general movement of the left. The mass mobilization around Black Lives Matter has fallen out of the public eye, thanks to uncritical coverage of the strident ideological counter-offensive of the right via the moral panics around critical race theory and an alleged nationwide resurgence in violent crime. There are not even any left-wing intellectuals of sufficient stature willing or able to provide a clear analysis of the events of January 6 to the public.

This means that the institutional defense of what remains of American democracy largely comes down to Congress and the press, two deeply unpopular institutions that are each in different ways passing into ever greater control of the right. The final firewall here may well become the bureaucratic organs of the Justice Department and the national security state. These top-down responders to the democracy crisis often win the favor of liberals, but throughout the Trump era we’ve seen they are of limited use in solving what is essentially a political problem. It’s clear that whatever indictments and arrests may be forthcoming within the insurrection’s leadership caste, the right is prepared to make political hay out of them, by positioning themselves yet again as victims of a deep-state conspiracy.

The defensive posture of the American left has thus become a study in oscillating anxiety: There’s a pronounced penchant on the one hand for hand-wringing and the inflation of fears that paralyze collective action; and on the other hand, a tendency to nervously whistle in the dark–making light of or diminishing the actual importance of what’s occurred. A year after the convulsions of January 6, the left still has provided no convincing political answer to the insurrection, preferring instead to leave the question to a mainstream liberalism that has repeatedly failed to halt the advance of the far right into the center of American politics. So far, the extreme right’s efforts have been shambolic, disorganized, and weak, but their aim is clear–and they may quickly learn from their mistakes.

John Ganz is a writer living in New York. He writes the newsletter Unpopular Front and is working on a book about American politics in the early 1990s.